Unix, the Minicomputer, and the Workstation

Monday, February 9th, 2026Previously, I described the rise of Norsk Data in the minicomputer market and the challenges it faced, shared with other minicomputer manufacturers like Digital, but also mainframe companies like ICL and IBM, along with other technology companies like Xerox. Norsk Data may have got its commercial start in shipboard computers, understandable given Norway’s maritime heritage, but its growth was boosted by a lucrative contract with CERN to supply the company’s 16-bit minicomputers for use in accelerator control systems. Branching out into other industries and introducing 32-bit processors raised the company’s level of ambition, and soon enough Norsk Data’s management started seeing the company as a credible rival to Digital and other established companies.

Had the minicomputing paradigm remained ascendant, itself disrupting the mainframe paradigm, then all might have gone well, but just as Digital and others had to confront the emergence of personal computing, so did Norsk Data. Various traditional suppliers including Digital were perceived as tackling the threat from personal computers rather ineffectively, but they could not be accused of not having a personal computing strategy of their own. The strategists at Norsk Data largely stuck to their guns, however, insisting that minicomputers and terminals were the best approach to institutional computing.

Adamant that their NOTIS productivity suite and other applications were compelling enough reasons to invest in their systems, they tried to buy their way into new markets, ignoring the dynamics that were leading customers in other directions and towards other suppliers. Even otherwise satisfied customers were becoming impatient with the shortcomings of Norsk Data’s products and its refusal to engage substantially with emerging trends like graphical user interfaces, demonstrated by the Macintosh, a variety of products available for IBM-compatible personal computers, and the personal graphical workstation.

Worse is not Better

With Norsk Data’s products under scrutiny for their suitability for office applications, other deficiencies in their technologies were identified. The company’s proprietary SINTRAN III operating system still only offered a non-hierarchical filesystem as standard, with a conservative limit on the number of files each user could have. By late 1984, the Acorn Electron, my chosen microcomputer from the era, could support a hierarchical filesystem on floppy disks. And yet, here we have a “superminicomputer” belatedly expanding its file allowance in a simple, flat, user storage area from 256 files to an intoxicating 4096 on a comparatively huge and costly storage volume.

As one report noted, “a fundamental need with OA systems is for a hierarchical system”, which Norsk Data had chosen to provide via a separate NOTIS-DS (Data Storage) product, utilising a storage database that was generally opaque to the operating system’s own tools. A genuine hierarchical filesystem was apparently under development for SINTRAN IV, distinct from efforts to provide the hierarchical filesystem demanded by the company’s Unix implementation, NDIX.

SINTRAN’s advocates seem to have had the same quaint ideas about commands and command languages as advocates of other systems from the era, bemoaning “terse” Unix commands and its “powerful but obscure” shell. Some of them have evidently wanted to have it both ways, trotting out how the command to list files, being one that prompted the user in various ways, could be made to operate in a more concise and less interactive fashion if written in an abbreviated form. Commands and filenames could generally be abbreviated and still be located if the abbreviation could be unambiguously expanded to the original name concerned.

Of course, such “magic” was just a form of implicitly applying wildcard characters in the places where hyphens were present in an abbreviated name, and this could presumably have been problematic in certain situations. It comes across as a weak selling point indeed, at least if one is trying to highlight the powerful features of an operating system, rather than any given command shell. Especially when the humble Acorn Electron also supported things like abbreviated commands and abbreviated BASIC keywords, the latter often being a source of complaint by reviewers appalled at the effects on program readability.

For real-time purposes, SINTRAN III seemingly stacked up well against Digital’s RSX-11M, and offered a degree of consistency between Norsk Data’s 16- and 32-bit environments. Nevertheless, its largely satisfied users saw the benefits in what Unix could provide and hoped for an environment where SINTRAN and Unix could coexist on the same system, with the former supporting real-time applications.

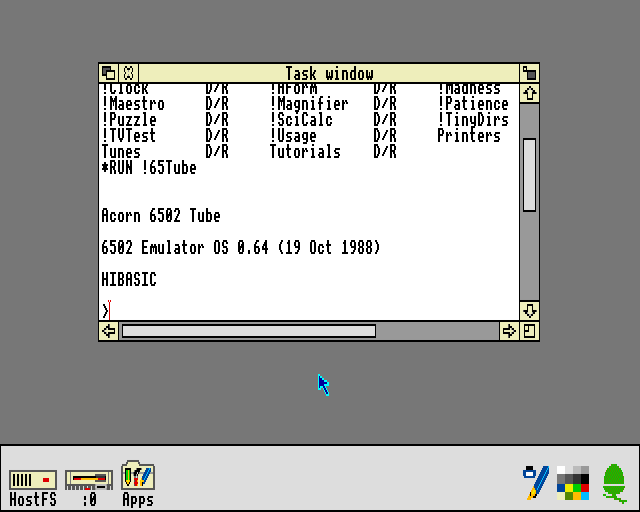

Perhaps taking such remarks into account, Norsk Data commissioned Logica to port 4.2BSD to the ND-500 family. Due to the architecture of such systems, its Unix implementation, NDIX, would run on the ND-500 processor but lean on the ND-100 front-end processor running SINTRAN for peripheral input/output and other support, such as handling interrupts occurring on the ND-500 processor itself, introducing the notion of “shadow programs”, “shadow processes”, or “twin processes” running on the ND-100 to support the handling of page faults.

Burdening the 16-bit component of the system with the activity of its more powerful 32-bit companion processor seems to have led to some dissatisfaction with the performance of the resulting system. Claims of such problems, particularly in connection with NDIX, being resolved and delivering a better experience than a VAX-11/785 seem rather fragile given the generally poor adoption of NDIX and the company’s unwillingness to promote it. Indeed, in 1988, amidst turbulent times and the need to adapt to market realities, Unix at Norsk Data was something apparently confined to Intel-based systems running SCO Unix and merely labelled up to look like models in the ND-5000 range that had succeeded the ND-500.

Half-hearted adoption of Unix was hardly confined to Norsk Data. Unix had been developed on Digital hardware and that company had offered a variant for its PDP-11 systems, but it only belatedly brought its VAX-based product, Ultrix, to that system in 1984, seven years after the machine’s introduction. Even then, certain models in various ranges would not support Ultrix, or at least not initially. Mitigating this situation was the early and continuing availability of the Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) for the platform, this having been the basis for Ultrix itself.

Mainframe incumbents like IBM and ICL were also less than enthusiastic about Unix, at least as far as those mainframes were concerned. ICL developed a Unix environment for its mainframe operating system before going round again on the concept and eventually delivering its VME/X product to a market that, after earlier signals, perhaps needed to be convinced that the company was truly serious about Unix and open systems.

IBM had also come across as uncommitted to Unix, in contrast to its direct competitor in the mainframe market, Amdahl, whose implementation, UTS, had resulted from an early interest in efforts outside the company to port Unix to IBM-compatible mainframe hardware. IBM had contracted Interactive Systems Corporation to do a Unix port for the PC XT in the form of PC/IX, and as a response to UTS, ISC also did a port called IX/370 to IBM’s System/370 mainframes. Thereafter, IBM would partner with Locus Computing Corporation to make AIX PS/2 for its personal computers and, eventually in 1990, AIX/370 to update its mainframe implementation.

IBM’s Unix efforts coincided with its own attempts to enter the Unix workstation market, initially seeing limited success with the RT PC in 1985, and later seeing much greater success with the RS/6000 series in 1990. ICL seemed more inclined to steer customers favouring Unix towards its DRS “departmental” systems, some of which might have qualified as workstations. Both companies increasingly found themselves needing to convince such customers that Unix was not just an afterthought or a cynical opportunity to sell a few systems, but a genuine fixture in their strategies, provided across their entire ranges. Nevertheless, ICL maintained its DRS range and eventually delivered its DRS 6000 series, allegedly renamed from DRS 600 to match IBM’s model numbering, based on the SPARC architecture and System V Unix.

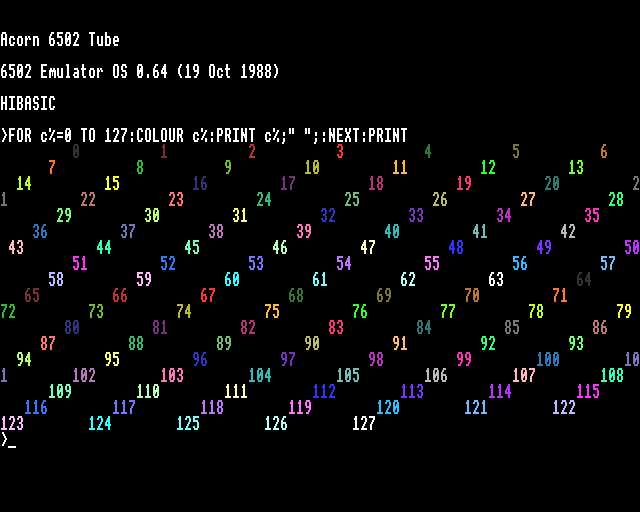

A lack of enthusiasm for Unix amongst minicomputer and mainframe vendors contrasted strongly with the aspirations of some microcomputer manufacturers. Acorn’s founder Chris Curry articulated such enthusiasm early in the 1980s, promising an expansion to augment the BBC Micro and possibly other models that would incorporate the National Semiconductor 32016 processor and run a Unix variant. Acorn’s approach to computer architecture in the BBC Micro was to provide an expandable core that would be relegated to handling more mundane tasks as the machine was upgraded to newer and better processors, somewhat like the way a microcontroller may be retained in various systems to handle input and output, interrupts and so on.

(Meanwhile, another microcomputer, the Dimension 68000, took the concept of combining different processors to an extreme, but unlike Acorn’s more modest approach of augmenting a 6502-based system with potentially more expensive processor cards, the Dimension offered a 68000 as its main processor to be augmented with optional processor cards for a 6502 variant, Z80 and 8086, these providing “emulation” capabilities for Apple, Kaypro and IBM PC systems respectively. Reviewers were impressed by the emulation support but unsure as to the demand for such a product in the market. Such hybrid systems seem to have always been somewhat challenging to sell.)

Acorn reportedly engaged Logica to port Xenix to the 32016, despite other Unix variants already existing, including Genix from National itself along with more regular BSD variants seen on the Whitechapel MG-1. Financial and technical difficulties appear to have curtailed Acorn’s plans, some of the latter involving the struggle for National to deliver working silicon, but another significant reason involves Acorn’s architectural approach, the pitfalls of which were explored and demonstrated by another company with connections to Acorn from the early 1980s, Torch Computers.

Tasked with covering the business angle of the BBC Micro, Torch delivered the first Z80 processor expansion for the system. The company then explored Acorn’s architectural approach by releasing second processor expansions that featured the Motorola 68000, intended to run a selection of operating systems including Unix. Although products were brought to market, and some reports even suggested that Torch had become one of the principal Unix suppliers in the UK in selling its Unicorn-branded expansions, it became evident that connecting a more powerful processor to an 8-bit system and relying on that 8-bit system to be responsible for input and output processing rather impeded the performance of the resulting system.

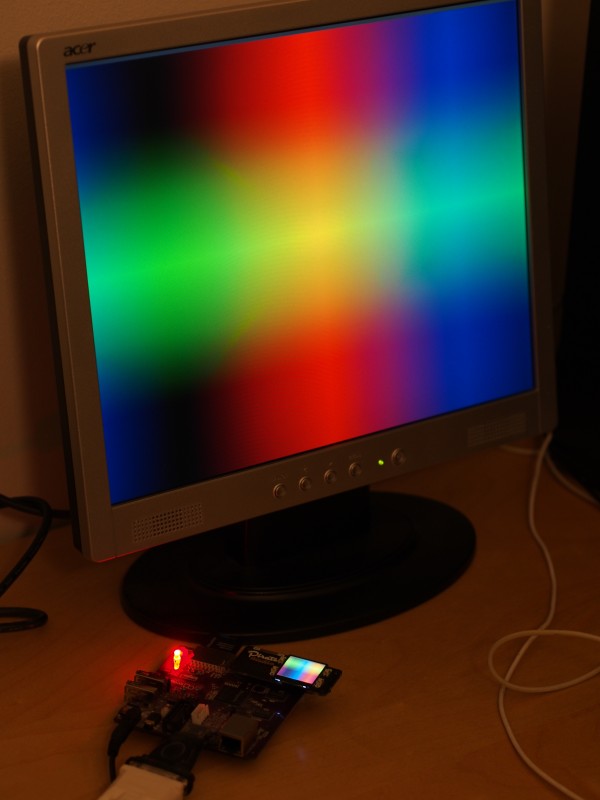

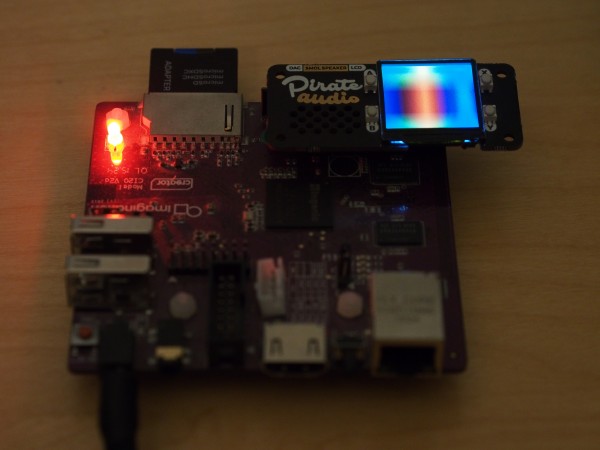

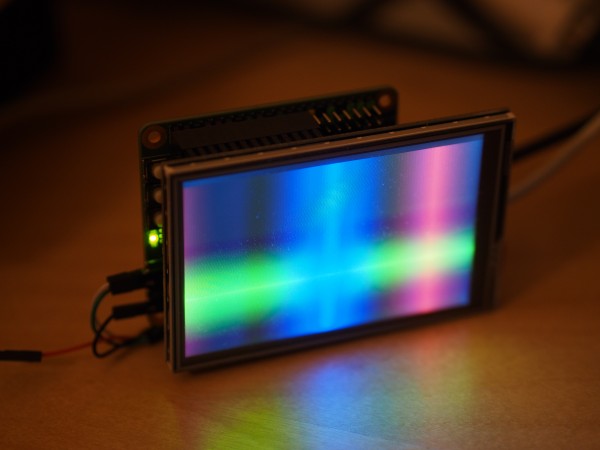

While servicing things like keyboards and printers were presumably within the capabilities of the “host” 8-bit system, storage needed higher bandwidth, particularly if hard drives were to be employed, and especially if increasingly desirable features such as demand paging were to be available in any Unix implementation. Torch realised that to remedy such issues, they would need to design a system from scratch, with the main processor and supporting chips having direct access to storage peripherals, leaving pretty much all of the 8-bit heritage behind. Their Triple-X workstation utilised the 68010 and offered a graphical Unix environment, elements of which would be licensed by NeXT for its own workstations.

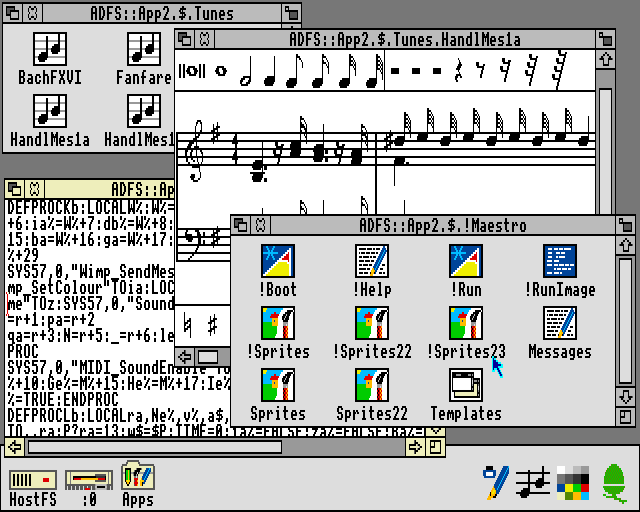

Out of Acorn’s abandoned plans for a range of business machines, the company’s Cambridge Workstation, consisting of a BBC Micro with the 32016 expansion plus display, storage and keyboard, ran a proprietary operating system that largely offered the same kind of microcomputing paradigm as the BBC Micro, boosted by high-level language compilers and tools that were far more viable on the 32016 than the 6502. Nevertheless, Unix would remain unsupported, the memory management unit omitted from delivered forms of the Cambridge Workstation and related 32016 expansion. Eventually, Acorn would bring a more viable product to market in the form of its R-series workstations: entirely 32-bit machines based on the ARM architecture, albeit with their own shortcomings.

Norsk Data had also contracted out its Unix porting efforts to Logica, but unlike IBM, who had grasped the nettle with both hands to at least give the impression of taking Unix support seriously, Norsk Data took on the development of NDIX and seemingly proceeded with it begrudgingly, only belatedly supporting the models that were introduced. Even in captive markets where opportunities could be engineered, such as in the case of one initiative where Norsk Data systems were procured by the Norwegian state under a dubious scheme that effectively subsidised the company through sales of systems and services to regional computing centres, the models able to run NDIX were not necessarily the expensive flagship models that were sold in. With limited support for open systems and an emphasis on the increasingly archaic terminal-based model of providing computing services, that initiative was a costly failure.

Had NDIX been a compelling product, Norsk Data would have had a substantial incentive to promote it. From various documents, it seems that a certain amount of the NDIX development work was carried out at Norsk Data’s UK subsidiary, perhaps suffering in the midst of Wordplex-related intrigues towards the end of the 1980s. But at CERN, where demand might have been more easily generated, NDIX was regarded as “not being entirely satisfactory” after two years of effort trying to deliver it on the ND-500 series. The 16-bit ND-100 front-end processor was responsible for input and output, including to storage media, and the overheads imposed by this slower, more constrained system, undermined the performance of Unix on the ND-500.

Norsk Data, in conjunction with its partners and customers, had rediscovered what Torch had presumably identified in maybe 1984 or 1985 before that company swiftly pivoted to a new systems architecture to more properly enter the Unix workstation business at the start of 1986. One could argue that the ND-5000 series and later refinements, arriving from 1987 onwards, would change this situation somewhat for Norsk Data, but time and patience were perhaps running out even in the most receptive of environments to these newer developments.

The Spectre of the Workstation

The workstation looms large in the fate of Norsk Data, both as the instrument of its demise as well as a concept the company’s leadership never really seemed to fathom. Already in the late 1970s, the industry was being influenced by work done at Xerox on systems such as the Alto. Companies like Three Rivers Computer Corporation and Apollo Computer were being founded, and it was understandable that others, even in Norway, might be inspired and want a piece of the action.

To illustrate how the fate of many of these companies is intertwined, ICL had passed up on the opportunity of partnering with Apollo, choosing Three Rivers and adopting their PERQ workstation instead. At the time, towards the end of the 1970s, this seemed like the more prudent strategy, Three Rivers having the more mature product and being more willing to commit to Unix. But Apollo rapidly embraced the Motorola 68000 family, while the PERQ remained a discrete logic design throughout its commercial lifetime, eventually being described as providing “poor performance” as ICL switched to reselling Sun workstations instead.

Within Norsk Data, several engineers formulated a next-generation machine known as Nord-X, later deciding to leave the company and establish a new enterprise, Sim-X, to make computers with graphical displays based on bitslice technology, rather like machines such as the Alto and PERQ. One must wonder whether even at this early stage, a discussion was had about the workstation concept, only for the engineers to be told that this was not an area Norsk Data would prioritise.

Sim-X barely gets a mention in Steine’s account of the corporate history (“Fenomenet Norsk Data”, “The Norsk Data Phenomenon”), but it probably involves a treatment all by itself. The company apparently developed the S-2000 for graphical applications, initially for newspaper page layout, but also for other kinds of image processing. Later, it formed the basis of an attempt to make a Simula machine, in the same vein as the once-fashionable Lisp machine concept. Although Sim-X failed after a few years, one of its founders pursued the image processing system concept in the US with a company known as Lightspeed. Frustratingly minimal advertising for, and other coverage of, the Lightspeed Qolor can be found in appropriate industry publications of the era.

Since certain industry trends appear to have infiltrated the thinking at Norsk Data and motivated certain strategic decisions, it was not surprising that its early workstation efforts were focused on specific markets. It was not unusual for many computer companies in the early 1980s to become enthusiastic about computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM). Even microcomputer companies like Acorn and Commodore aspired to have their own CAD workstation, focused on electronic design automation (EDA) and preferably based on Unix, largely having to defer its realisation until a point in time when they had the technical capabilities to deliver something credible.

Norsk Data had identified a vehicle for such aspirations in the form of Dietz Computer Systems, producer of the Technovision CAD system for mechanical design automation. This acquisition seemed to work well for the combined company, allowing the CAD operation to take advantage of Norsk Data’s hardware and base complete CAD systems on it. Such special-purpose workstations were arguably justifiable in an era where particular display technologies were superior for certain applications and where computing resources needed to be focused on particular tasks. However, more versatile machines, again inspired by the Alto and PERQ, drove technological development and gradually eliminated the need to compromise in the utilisation of various technologies. For instance, screens could be high-resolution, multicolour and support vector and bitmap graphics at acceptable resolutions, even accelerating the vector graphics on a raster display to cater to traditional vector display applications.

In its key scientific and engineering markets, Norsk Data had to respond to industry trends and the activities of its competitors. Hewlett-Packard may have embraced Unix and introduced PA-RISC to its product ranges in 1986, largely to Norsk Data’s apparent disdain, but it had also introduced an AI workstation. Language system workstations had emerged in the early 1980s, initially emphasising Pascal as the PERQ had done. Lisp machines had for a time been all the rage, emphasising Lisp as a language for artificial intelligence, knowledge base development, and for application to numerous other buzzword technologies of the era, empowering individual users with interactive, graphical environments that were meant to confer substantial productivity benefits.

Thus, Norsk Data attempted to jump on the Lisp machine bandwagon with Racal, the company that would produce the telecoms giant Vodafone, hoping to leverage the ability to microcode the ND-500 series to produce a faster, more powerful system than the average Lisp machine vendor. Predictably, claims were made about this Knowledge Processing System being “10 to 20 times more powerful than a VAX” for the intended applications. Reportedly, the company delivered some systems, although Steine contradicts this, claiming that the only system that was sold – to the University of Oslo – was never delivered. This is not entirely true, either, judging from an account of a “a burned-up backplane” in the KPS-10 delivered to the Institute for Informatics. Intriguingly, hardware from one delivered system has since surfaced on the Internet.

One potentially insightful article describes the memory-mapped display capabilities of the KPS-10, supporting up to 36 bitmapped monochrome screens or bitplanes, with the hardware supposedly supporting communications with graphical terminals at distances of 100 metres, suggesting that, once again, the company’s dogged adherence to the terminal computing paradigm had overridden any customer demand for autonomous networked workstations. It had been noted alongside the ambitious performance claims that increased integration using gate arrays would make a “single-user work station” possible, but such refinements would only arrive later with the ND-5000 series. In the research community, Racal’s brief presence in the AI workstation market, aiming to support Lisp and Prolog on the ND-500 hardware, left users turning to existing products and, undoubtedly, conventional workstations once Racal and Norsk Data pulled out.

With Norsk Data having announced a broader collaboration with Matra in France, the two companies announced a planned “desktop minisupercomputer” emphasising vector processing, which is another area where competing vendors had introduced products in venues like CERN, threatening the adoption of Norsk Data’s products. Although the “minisupercomputer” aspect of such an effort might have positioned the product alongside other products in the category, the “desktop” label is a curious one coming from Norsk Data. Perhaps the company had been made aware of systems like the Silicon Graphics IRIS 4D and had hoped to capture some of the growing interest in such higher-performance workstations, redirecting that interest towards their own products and advocating for solutions similar to that of the KPS-10. In any case, nothing came of the effort, and so the company had nothing to show.

The intrusion of categories like “desktop” and “workstation” into Norsk Data’s marketing will have been the result of shifting procurement trends in venues like CERN. From being a core vendor to CERN, contracted to provide hardware under non-competitive arrangements, conditions in the organisation had started to change, and with efforts ramping up on the Large Electron-Positron collider (LEP), procurement directed towards workstations also started to ramp up. Initially, Apollo featured prominently, gaining from their “first mover” advantage, but they were later joined by Sun Microsystems. Even IBM’s PC RT had appealed to some in the organisation. And despite Digital being perceived as a minicomputer company, it was still managing to sell VAXstations into CERN.

One has to wonder what Norsk Data’s sales representatives in France must have made of it all. Hundreds of workstations from other companies being bought in, millions of Swiss francs being left on the table, and yet the models being brought to market for them to sell were based on the Butterfly workstation concept, featuring Technostation models for CAD and Teamstation models for NOTIS, neither of them likely to appeal to people looking beyond the personal computer and wanting workstation capabilities on their desk. A Butterfly workstation based on the 80286 running NOTIS on a 16-bit minicomputer expansion card must have seemed particularly absurd and feeble.

Increased integration brought the possibilities of smaller deskside systems from Norsk Data, with the ND-5800 and later models perhaps being more amenable to smaller workloads and workstation applications. But it seems that the mindset persisted of such systems being powerful minicomputers to be shared, rather than powerful workstations for individuals. Graphics cards embedding Motorola 68000 family processors augmented Technovision models targeting the CAD market, but as the end of the 1980s beckoned, such augmentations fell rather short of the kind of hardware companies like Sun and Silicon Graphics were offering. Meanwhile, only the company’s lower-end models could sell at around the kind of prices set by the mainstream workstation vendors, but with low-end performance to match.

In a retrospective of the company, chief executive Rolf Skår remarked that the workstation vendors had deliberately cut margins instead of charging what was considered to be the value of a computer for a particular customer, which is perhaps another way of describing a form of pricing where what the market will bear determines how high the price will be set, squeezing the customer as much as possible. The article, featuring an erroneous figure for the price of a typical Norsk Data computer (100,000 Norwegian crowns, being broadly equivalent to $10,000) misleads the reader into thinking that the company’s machines were not that expensive after all and even competitive on price with a typical Sun workstation.

Evidently, there was confusion from Skår or the writer about the currencies involved, and such a computer would tend to cost more like 1 million crowns or $100,000: ten times that of the most affordable workstations. Norsk Data’s top-end machines ballooned in price in the mid-1980s, costing up to $500,000 for some single-processor models, and potentially $1.5 million for the very top-end four-processor configurations. Even with Sun introducing its first SPARC-based model at around $40,000, it could still outperform such “peak minicomputer” VAX and Norsk Data models and sell at a tenth of the price.

Norsk Data’s opportunistic pricing presumably tracked that of its big rival, Digital, and its own pricing of VAX models, sensing that if promoted as faster or better than the VAX, then potential customers would choose the Norsk Data machine, pricing and other characteristics being generally similar. When companies might have bought into a system with a big investment in information technology, this might have been a viable strategy, but as such technology became cheaper and available from numerous other providers, it became harder even for Digital to demand such a premium.

One can almost sense a sort of accusation that the workstation manufacturers ruined it for everyone, cheapening an otherwise lucrative market, but workstations were, of course, just another facet of the personal computing phenomenon and the gradual democratisation of computing itself. In the end, customers were always going to choose systems that delivered the computing power and user experience they desired, and it was simply a matter of those companies identifying and addressing such desires and needs, making such systems available at steadily more affordable prices, eventually coming to dominate the market. That Norsk Data’s management failed to appreciate such emerging trends, even when spelled out in black and white in procurement plans involving considerable sums of money, suggests that the blame for the company’s growth bonanza eventually coming to an end lay rather closer to home.

The Performance Game

With the ND-500 series, Norsk Data had been able to deliver floating-point performance that was largely competitive within the price bracket of its machines, and favourable comparisons were made between various ND-500 models and those in the VAX line-up, not entirely unjustifiably. Manufacturers who had not emphasised this kind of computation in their products found some kind of salvation in the form of floating-point processors or accelerators, made available by specialists like Mercury Computer Systems and Floating Point Systems, aided by the emergence of floating-point arithmetic chips from AMD and Weitek.

Presumably to fill a gap in its portfolio, Digital offered the Floating Point Systems accelerators in combination with some models. Meanwhile, the company had improved the performance of its VAX 8000 series to ostensibly eliminate many of Norsk Data’s performance claims. And curiously, Matra, who were supposed to be collaborating with Norsk Data on a vector computer, even offered the FPS products with the Norsk Data systems it had been selling, presumably to remedy a deficiency in its portfolio, but it is difficult to really know with a company like Matra.

Prior to the introduction of the ND-5000 series in 1987, Norsk Data had largely kept pace with their perceived competitors, alongside a range of other companies emphasising floating-point computation, but the company now needed to re-establish a lead over those competitors, particularly Digital. The ND-5000 series, employing CMOS gate array technology, was labelled as a “vaxkiller” in aggressive publicity but initially fell short of Norsk Data’s claims of better performance than the two-processor VAX 8800.

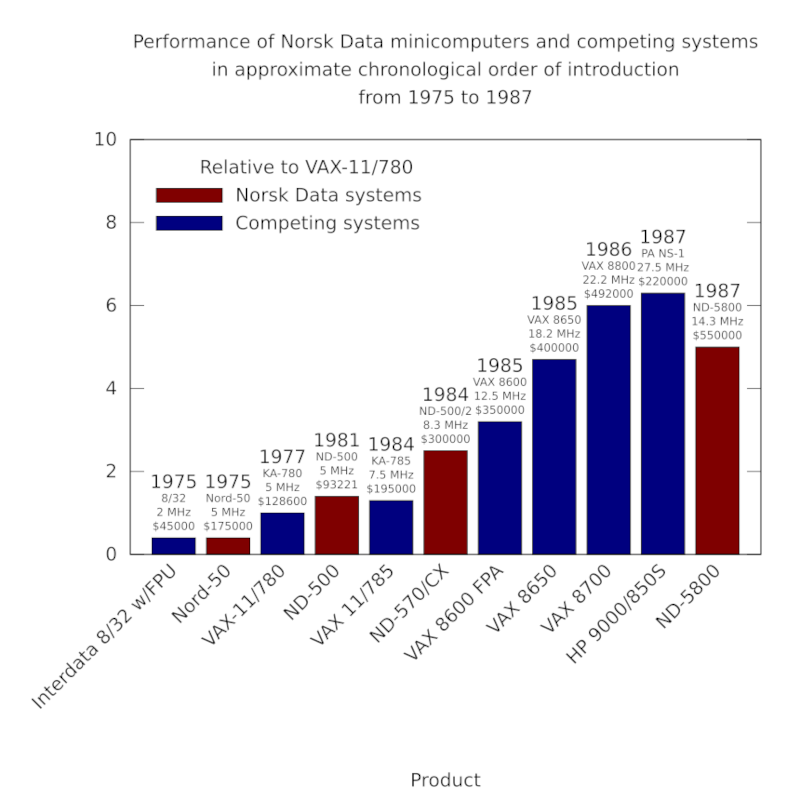

Using the only figures available to us, the top-end single-processor ND-5800 managed only 6.5 MWIPS and thus around 5 times the performance of the original VAX-11/780. In contrast, the dual-processor VAX 8800 was rated at around 9 times faster than its ancestor, with the single-processor VAX 8700 (later renamed to 8810) rated at around 6 times faster. All of these machines cost around half a million dollars. And yet, 1987 had seen some of the more potent first-generation RISC systems arrive in the marketplace from Hewlett-Packard and Silicon Graphics, both effectively betting their companies on the effectiveness of this technological phenomenon.

The performance of Norsk Data minicomputers and their competitors from 1975 to 1987. Although the ND-500 models were occasionally faster than the VAX machines at floating-point arithmetic, according to Whetstone benchmark results, Digital steadily improved its models, with the VAX 8700 of 1986 introducing similar architectural improvements to those introduced in the ND-5000 processors. Note how one of Hewlett-Packard’s first PA-RISC systems makes its mark alongside these established architectures.

Just as Digital’s management had kept RISC efforts firmly parked in the realm of “research”, even with completed RISC systems running Unix and feeding into more advanced research, Norsk Data’s technical leadership publicly dismissed RISC as a fad and their RISC competitors as unimpressive, even though the biggest names in computing – IBM, HP and Motorola – were at that very moment, formulating, developing and even delivering RISC products that threatened Norsk Data’s own products. RISC processors influenced and transformed the industry, and as the 1990s progressed, further performance gains were enabled by RISC architectural design principles.

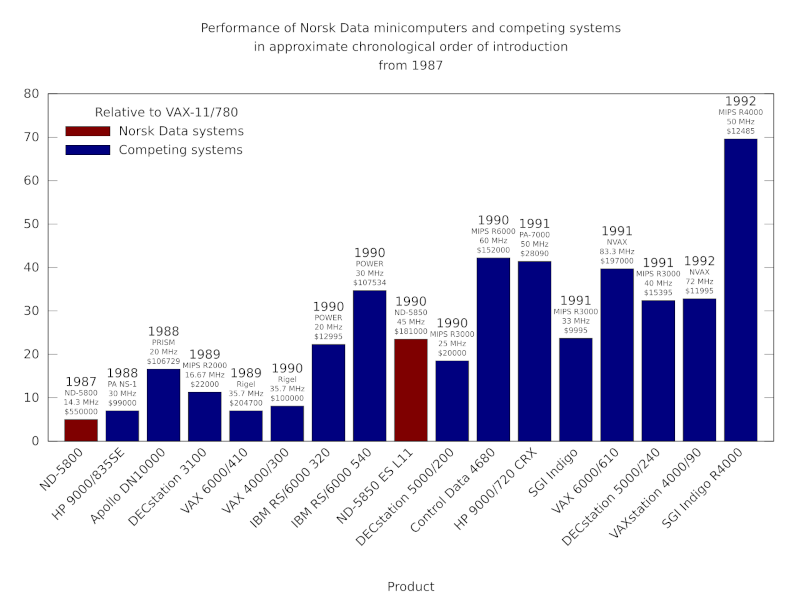

To be fair to the designers at both Digital and Norsk Data, they also incorporated techniques often associated with RISC, just as Motorola had done while still downplaying the RISC phenomenon. The VAX 8800 and ND-5800 thus incorporated architectural improvements over their predecessors, such as pipelining, that provided at least a doubling of performance. The ND-5000 ES range, announced in 1988 and apparently available from 1989, were claimed to deliver another doubling in performance, seemingly through increasing the operating frequency. This, however, would merely put such server products alongside relatively low-cost RISC workstations using the somewhat established MIPS R2000 processor.

With Digital’s VAX 9000 project stalling, it was left to the CVAX, Rigel and NVAX processors to progressively follow through with the enhancements made in the VAX 8800, propagating them to more highly integrated processors and producing considerably faster and cheaper machines towards the end of the 1980s and into the early 1990s. But this consolidation, starting with the VAX 6000 series, and the accompanying modest gains in performance led to customer unease about the trailing performance of VAX systems, particularly amongst those customers interested in running Unix.

Thus, Digital introduced workstations and servers based on the MIPS architecture, delivering a performance boost almost immediately to those customers. A VAX 6000 processor could deliver around 7 times the performance of the original VAX-11/780, whereas a MIPS R2000-based DECstation 3100 could deliver around 11 times the performance. Crucially, such systems did not cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, but mere tens of thousands, with the lowest-end workstations costing barely ten thousand dollars.

To keep pace with these threats, it seems that Norsk Data’s final push involved a ramping up of the ND-5830 “Rallar” processor from an operating frequency of 25MHz to 45MHz in 1990 or so, just as the MIPS R3000 was proliferating in products from several vendors at more modest 25MHz and 33MHz frequencies but still nipping at the heels of this final, accelerated ND-5850 product. MIPS would suffer delays and limited availability of faster products like the R6000, also bringing consequences to the timely delivery of its 64-bit R4000 architecture. Nevertheless, products from IBM in its emerging RS/6000 range would arrive in the same year and demonstrate comprehensively superior performance to Norsk Data’s entire range.

Whetstone benchmark figures, particularly for the latter ND-5830 and ND-5850, are impressive. However, there may be caveats to claims of competitive performance. In one case, a ND-5800 system was reported as running a computational model in around 5 minutes with one set of parameters and 70 minutes with another. Meanwhile, the same inputs required respective running times of around 9 minutes and 78 minutes on a VAXstation 3500. The VAXstation 3500 was a 3 MWIPS system, whereas the ND-5800 was rated at around 6.5 MWIPS, and yet for a larger workload, it seems that any floating-point processing advantage of the ND-5800 was largely eliminated.

As for the integer or general performance of the ND-500 and ND-5000 families, Norsk Data appear to have been evasive. The company used “MIPS” to mean Whetstone MIPS, measuring floating-point performance, which was perhaps excusable for “number crunchers” but less applicable to other applications and a narrow measure that gave way to others over time, anyway. Otherwise, “relative performance” measures and numbers of users were often given, leaving us to wonder how the systems actually stacked up. LINPACK benchmark figures are few and far between, which is odd given the emphasis Norsk Data made on numerical computation when promoting the systems.

Another benchmark employed by Norsk Data concerned the company’s pivot to the “transaction processing” market with their high-end systems. Introducing the tpServer series based on its final ND-5000 range, the company stated a TP1 benchmark score of 10 transactions per second for its single-processor ND-5700 model, with a relative performance factor suggesting around 30 transactions per second for its single-processor ND-5850 model. Interestingly, its Uniline 88 range, introduced as the company also pivoted to more mainstream technology, was based on the Motorola 88000 architecture and also appears to have offered around 30 transactions per second, with similar scalability options involving up to four processors as with its tpServer and other traditional products.

The MC88100 used in the Uniline 88 showed similar general performance to competitors using the MIPS R3000 and SPARC processors, so we might conclude that the ND-5850 may have been comparable to and competitive with the mainstream at the turn of the 1990s. But this would mean that the ND-5000 series no longer offered any hope of differentiating itself from the mainstream in terms of performance. With Unix not being prioritised for the series, either, further development of the platform must have started to look like a futile and costly exercise, appealing to steadily fewer niche customers and gradually losing the revenue necessary for the substantial ongoing investment needed to keep it competitive. Switching to the 88000 family would give comparable performance, established and accepted Unix implementations, and broader industry support.

The ND-5850 arrived at a time when the MIPS R6000 and products from other industry players were experiencing difficulties in what might be considered a detour into emitter-coupled logic (ECL) fabrication, motivated by the purported benefits of the technology, somewhat replaying events from earlier times. Back in 1987, Norsk Data, had reportedly resisted the temptation to adopt ECL, sticking with the supposedly “ignored” (but actually ubiquitous) CMOS technology, and advertising this wisdom in the press. MIPS and Control Data Corporation would eventually bring the R6000 to market, but with far less success than hoped.

History would run full circle, however, and with the ND-5000 architecture having been consigned to maintenance status, and with Norsk Data having adopted the Motorola 88000 architecture for future high-end products, the engineering department of Norsk Data, spun-out into a separate company, would describe its plans of developing a superscalar variant of the 88000 to be fabricated in ECL and known as ORION. Perhaps not unsurprisingly, such plans met insurmountable but unspecified technical obstacles, and the product effectively evaporated, ending all further transformative aspirations in the processor business. Meanwhile, MIPS would, from 1992 onwards, at least have the consolation of delivering the 64-bit R4000 to market, aided by its CMOS fabrication partners.

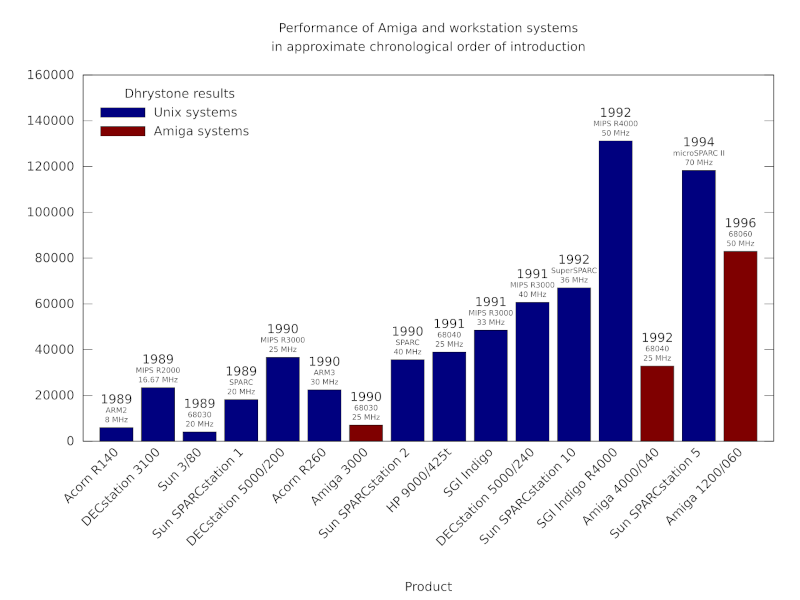

The performance of Norsk Data minicomputers and their competitors from 1987 onwards. The steady introduction of RISC products from Hewlett-Packard, Apollo Computer, Digital, IBM and others made the competitive landscape difficult for a low-volume manufacturer like Norsk Data. The company was soon having to contend with far cheaper workstation products from its competitors delivering comparable or superior performance (typically measured using SPECmark or SPECfp92 benchmarks here). Digital’s VAX products were also steadily improved and cost-reduced, but were eventually phased out in favour of Digital’s Alpha systems. In 1992, somewhat delayed, the MIPS R4000 appeared in systems like the SGI Indigo, offering a doubling of performance and maintaining the relentless pace of mainstream processor development.

Regardless, of whether specific Norsk Data products were better than specific products from its competitors, one is left wondering about that idea of Norsk Data making floating-point accelerators for other systems. After all, the ND-500 and ND-5000 processors were effectively accelerators for Norsk Data’s own 16-bit systems. And with that path having been taken, one might wonder whether the company would be the one having its offerings bundled by the likes of Digital. That a focus on such a market might have driven development at a faster tempo, pushing the company into the territory of floating-point specialists, minisupercomputers, and a lucrative market that would last until general-purpose products remedied their floating-point deficiencies, coupled with the rise of the RISC architectures.

Splitting off the floating-point expertise and coupling it with a variety of architectures in the form of a floating-point unit could have been an option. Indeed, Weitek, who had made such products the focus of their business apparently fabricated some of Norsk Data’s floating-point hardware for its later machines. Maybe there was good money in VLSI-fabricated Norsk Data accelerators for personal computers and workstations without great numeric processing options.

One might also wonder whether Norsk Data could have coupled its expertise in floating-point processing with an attractive instruction set architecture. Sadly, the company seemed wedded to the ND-500 architecture for compatibility reasons, involving an operating system that was not attractive to most potential customers, along with software that should have been portable and may not have been as desirable as perceived, anyway. Protecting the mirage of competitive advantage locked one form of expertise and potential commercial exploitation into others that were impeding commercial success.

The designers of the ND-5000 may have insisted that they could still match RISC designs even with their “complex instructions”, but Digital’s engineers had already concluded that their own comparable efforts to streamline VAX performance, achieving four- or five-fold gains within a couple of years, would remain inherently disadvantaged by the need to manage architectural complexity:

“So while VAX may “catch up” to current single-instruction-issue RISC performance, RISC designs will push on with earlier adoption of advanced implementation techniques, achieving still higher performance. The VAX architectural disadvantage might thus be viewed as a time lag of some number of years.”

In jettisoning the architectural baggage of the ND-500 architecture, Norsk Data’s intention was presumably to be able to more freely apply its expertise to the 88000 architecture, but all of this happened far too late in the day. To add insult to injury, it also involved the choice of what proved to be another doomed processor architecture.