Common Threads of Computer Company History

Tuesday, August 5th, 2025When descending into the vaults of computing history, as I have found myself doing in recent years, and with the volume of historical material now available for online perusal, it has largely become possible to finally have the chance of re-evaluating some of the mythology cultivated by certain technological communities, some of it dating from around the time when such history was still being played out. History, it is said, is written by the winners, and this is true to a large extent. How often have we seen Apple being given the credit for many technological developments that were actually pioneered elsewhere?

But the losers, if they may be considered that, also have their own narratives about the failure of their own favourites. In “A Tall Tale of Denied Glory”, I explored some myths about Commodore’s Amiga Unix workstation and how it was claimed that this supposedly revolutionary product was destined for success, cheered on by the big names in workstation computing, only to be defeated by Commodore’s own management. The story turned out to be far more complicated than that, but it illustrates that in an earlier age where there was more limited awareness of an industry with broader horizons than many could contemplate, everyone could get round a simplistic tale and vent their frustration at the outcome.

Although different technological communities, typically aligned with certain manufacturers, did interact with each other in earlier eras, even if the interactions mostly focused on advocacy and argument about who had chosen the best system, there was always the chance of learning something from each other. However, few people probably had the opportunity to immerse themselves in the culture and folklore of many such communities at once. Today, we have the luxury of going back and learning about what we might have missed, reading people’s views, and even watching television programmes and videos made about the systems and platforms we just didn’t care for at the time.

It was actually while searching for something else, as most great discoveries seem to happen, that I encountered some more mentions of the Amiga Unix rumours, these being relatively unremarkable in their familiarity, although some of them were qualified by a claim by the person airing these rumours (for the nth time) that they had, in fact, worked for Sun. Of course, they could have been the mailboy for all I know, and my threshold for authority in potential source material for this matter is now set so high that it would probably have to be Scott McNealy for me to go along with these fanciful claims. However, a respondent claimed that a notorious video documenting the final days of Commodore covered the matter.

I will not link to this video for a number of reasons, the most trivial of which is that it just drags on for far too long. And, of course, one thing it does not substantially cover is the matter under discussion. A single screen of text just parrots the claims seen elsewhere about Sun planning to “OEM” the Amiga 3000UX without providing any additional context or verification. Maybe the most interesting thing for me was to see that Commodore were using Apollo workstations running the Mentor Graphics CAD suite, but then so were many other companies at one point in time or other.

In the video, we are confronted with the demise of a company, the accompanying desolation, cameraderie under adversity, and plenty of negative, angry, aggressive emotion coupled with regressive attitudes that cannot simply be explained away or excused, try as some commentators might. I found myself exploring yet another rabbit hole with a few amusing anecdotes and a glimpse into an era for which many people now have considerable nostalgia, but one that yielded few new insights.

Now, many of us may have been in similar workplace situations ourselves: hopeless, perhaps even deluded, management; a failing company shedding its workforce; the closure of the business altogether. Often, those involved may have sustained a belief in the merits of the enterprise and in its products and people, usually out of the necessity to keep going, whether or not the management might have bungled the company’s strategy and led it down a potentially irreversible path towards failure.

Such beliefs in the company may have been forged in earlier, more successful times, as a company grows and its products are favoured over those of the competition. A belief that one is offering something better than the competition can be highly motivating. Uncalibrated against the changing situation, however, it can lead to complacency and the experience of helplessly watching as the competition recover and recapture the market. Trapped in the moment, the sequence of events leading to such eventualities can be hard to unravel, and objectivity is usually left as a matter for future observers.

Thus, the belief often emerges that particular companies faced unique challenges, particularly by the adherents of those companies, simply because everything was so overwhelming and inexplicable when it all happened, like a perfect storm making an unexpected landfall. But, being aware of what various companies experienced, and in peeking over the fence or around the curtain at what yet another company may have experienced, it turns out that the stories of many of these companies all have some familiar, common themes. This should hardly surprise us: all of these companies will have operated largely within the same markets and faced common challenges in doing so.

A Tale of Two Companies

The successful microcomputer vendors of the 1980s, which were mostly those that actually survived the decade, all had to transition from one product generation to the next. Acorn, Apple and Commodore all managed to do so, moving up from 8-bit systems to more sophisticated systems using 32-bit architectures. But these transitions only got them so far, both in terms of hardware capabilities and the general sophistication of their systems, and by the early 1990s, another update to their technological platforms was due.

Acorn had created the ARM processor architecture, and this had mostly kept the company competitive in terms of hardware performance in its traditional markets. But it had chosen a compromised software platform, RISC OS, on which to base its Archimedes systems. It had also introduced a couple of Unix workstation products, themselves based on the Archimedes hardware, but these were trailing the pace in a much more competitive market. Acorn needed the newly independent ARM company to make faster, more capable chips, or it would need embrace other processor architectures. Without such a boost forthcoming, it dropped Unix and sought to expand in “longshot” markets like set-top boxes for video-on-demand and network computing.

Commodore had a somewhat easier time of it, at least as far as processors were concerned, riding on the back of what Motorola had to offer, which had been good enough during much of the 1980s. Like Acorn, Commodore made their own graphics chips and had enjoyed a degree of technical superiority over mainstream products as a result, but as Acorn had experienced, the industry had started to catch up, leading to a scramble to either deliver something better or to go with the mainstream. Unlike Acorn, Commodore did do a certain amount of business actually going with the mainstream and selling IBM-compatible PCs, although the increasing commoditisation of that business led the company to disengage and to focus on its own technologies.

Commodore had its own distractions, too. While Acorn pursued set-top boxes for high-bandwidth video-on-demand and interactive applications on metropolitan area networks, Commodore tried to leverage its own portfolio rather more directly, trading on its strengths in gaming and multimedia, hoping to be the one who might unite these things coherently and lucratively. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Japanese games console manufacturers had embraced the Compact Disc format, but NEC’s PC Engine CD-ROM² and Sega’s Mega-CD largely bolted CD technology onto existing consoles. Philips and Sony, particularly the former, had avoided direct competition with games consoles, pitching their CD-i technology more at the rather more sedate “edutainment” market.

With CDTV, Commodore attempted to enter the same market at Philips, downplaying the device’s Amiga 500 foundations and fast-tracking the product to market, only belatedly offering the missing CD-ROM drive option for its best-selling Amiga 500 system that would allow existing customers to largely recreate the same configuration themselves. Both CD-i and CDTV were considered failures, but Commodore wouldn’t let go, eventually following up with one of the company’s final products, the CD32, aiming more directly at the console market. Although a relative success against the lacklustre competition, it came too late to save the company which had entered a steep decline only to be driven to bankruptcy by a patent aggressor.

Whether plucky little Commodore would have made a comeback without financial headwinds and patent industry predators is another matter. Early multimedia consoles had unconvincing video playback capabilities without full-motion video hardware add-ons, but systems like the 3DO Interactive Multiplayer sought to strengthen the core graphical and gaming capabilities of such products, introducing hardware-accelerated 3D graphics and high-quality audio. Within only a year or so of the CD32’s launch, more complete systems such as the Sega Saturn and, crucially, the Sony PlayStation would be available. Commodore’s game may well have been over, anyway.

Back in Cambridge, a few months after Commodore’s demise, Acorn entered into a collaboration with an array of other local technology, infrastructure and media companies to deliver network services offering “interactive television“, video-on-demand, and many of the amenities (shopping, education, collaboration) we take for granted on the Internet today, including access to the Web of that era. Although Acorn’s core technologies were amenable to such applications, they did need strengthening in some respects: like multimedia consoles, video decoding hardware was a prerequisite for Acorn’s set-top boxes, and although Acorn had developed its own competent software-based video decoding technology, the market was coalescing around the MPEG standard. Fortunately for Acorn, MPEG decoder hardware was gradually becoming a commodity.

Despite this interactive services trial being somewhat informative about the application of the technologies involved, the video-on-demand boom fizzled out, perhaps demonstrating to Acorn once again that deploying fancy technologies in a relatively affluent region of the country for motivated, well-served early adopters generally does not translate into broader market adoption. Particularly if that adoption depended on entrenched utility providers having to break open their corporate wallets and spend millions, if not billions, on infrastructure investments that would not repay themselves for years or even decades. The experience forced Acorn to refocus its efforts on the emerging network computer trend, leading the company down another path leading mostly nowhere.

Such distractions arguably served both companies poorly, causing them to neglect their core product lines and to either ignore or to downplay the increasing uncompetitiveness of those products. Commodore’s efforts to go upmarket and enter the potentially lucrative Unix market had begun too late and proceeded too slowly, starting with efforts around Motorola 68020-based systems that could have opened a small window of opportunity at the low end of the market if done rather earlier. Unix on the 68000 family was a tried and tested affair, delivered by numerous companies, and supplied by established Unix porting houses. All Commodore needed to do was to bring its legendary differentiation to the table.

Indeed, Acorn’s one-time stablemate, Torch Computers, pioneered low-end graphical Unix computing around the earlier 68010 processor with its Triple X workstation, seeking to upgrade to the 68020 with its Quad X workstation, but it had been hampered by a general lack of financing and an owner increasingly unwilling to continue such financing. Coincidentally, at more or less the same time that the assets of Torch were finally being dispersed, their 68030-based workstation having been under development, Commodore demonstrated the 68030-based Amiga 3000 for its impending release. By the time its Unix variant arrived, Commodore was needing to bring far more to the table than what it could reasonably offer.

Acorn themselves also struggled in their own moves upmarket. While the ARM had arrived with a reputation of superior performance against machines costing far more, the march of progress had eroded that lead. The designers of the ARM had made a virtue of a processor being able to make efficient use of its memory bandwidth, as opposed to letting the memory sit around idle as the processor digested each instruction. This facilitated cheaper systems where, in line with the design of Acorn’s 8-bit computers, the processor would take on numerous roles within the system including that of performing data transfers on behalf of hardware peripherals, doing so quite effectively and obviating the need for costly interfacing circuitry that would let hardware peripherals directly access the memory themselves.

But for more powerful systems, the architectural constraints can be rather different. A processor that is supposedly inefficient in its dealings with memory may at least benefit from peripherals directly accessing memory independently, raising the general utilisation of the memory in the system. And even a processor that is highly effective at keeping itself busy and highly efficient at utilising the memory might be better off untroubled by interrupts from hardware devices needing it to do work for them. There is also the matter of how closely coupled the processor and memory should be. When 8-bit processors ran at around the same speed as their memory devices, it made sense to maximise the use of that memory, but as processors increased in speed and memory struggled to keep pace, it made sense to decouple the two.

Other RISC processors such as those from MIPS arrived on the market making deliberate use of faster memory caches to satisfy those processors’ efficient memory utilisation while acknowledging the increasing disparity between processor and memory speeds. When upgrading the ARM, Acorn had to introduce a cache in its ARM3 to try and keep pace, doing so with acclaim amongst its customers as they saw a huge jump in performance. But such a jump was long overdue, coming after Acorn’s first Unix workstation had shipped and been largely overlooked by the wider industry.

Acorn’s second generation of workstations, being two configurations of the same basic model, utilised the ARM3 but lacked a hardware floating-point unit. Commodore could rely on the good old 68881 from Motorola, but Acorn’s FPA10 (floating-point accelerator) arrived so late that only days after its announcement, three years or so after those ARM3-based systems had been launched and two years later than expected, Acorn discontinued its Unix workstation effort altogether.

It is claimed that Commodore might have skipped the 68030 and gone straight for the 68040 in its Unix workstation, but indications are that the 68040 was probably scarce and expensive at first, and soon only Apple would be left as a major volume customer for the product. All of the other big Motorola 68000 family customers had migrated to other architectures or were still planning to, and this was what Commodore themselves resolved to do, formulating an ambitious new chipset called Hombre based around Hewlett-Packard’s PA-RISC architecture that was never realised.

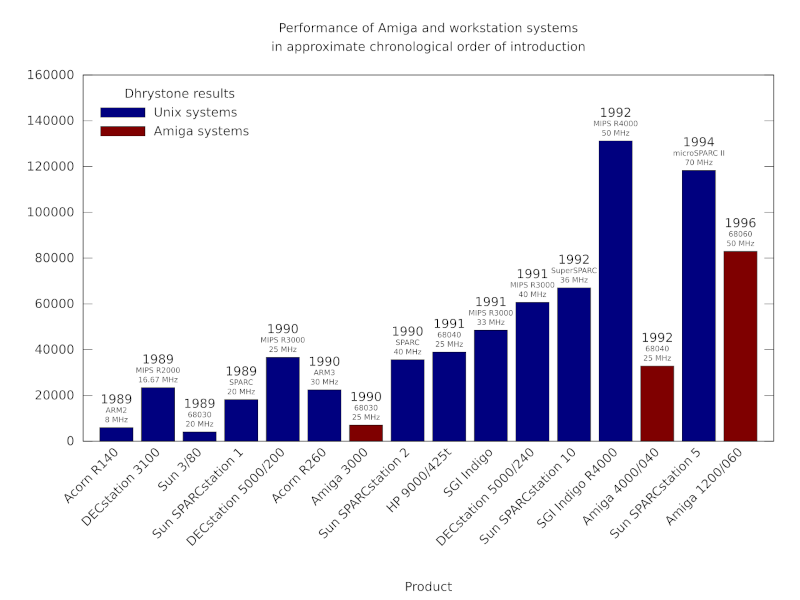

A chart showing how Unix workstation performance steadily improved, largely through the introduction of steadily faster RISC processors.

Acorn, meanwhile, finally got a chip upgrade from ARM in the form of the rather modest ARM6 series, choosing to develop new systems around the ARM600 and ARM610 variants, along with systems using upgraded sound and video hardware. One additional benefit of the newer ARM chips was an integrated memory management unit more suitable for Unix implementations than the one originally developed for the ARM. For followers of the company, such incoming enhancements provided a measure of hope that the company’s products would remain broadly competitive in hardware terms with mainstream personal computers.

Perhaps most important to most Acorn users at the time, given the modest gains they might see from the ARM600/610, was the prospect of better graphical capabilities, but Acorn chose not to release their intermediate designs along the way to their grand new system. And so, along came the Risc PC: a machine with two processor sockets and logic to allow one of the processors to be an x86-compatible processor that could run PC software. Once again, Acorn gave the whole hardware-based PC accelerator card concept another largely futile outing, failing to learn that while existing users may enjoy dabbling with software from another platform, it hardly ever attracts new customers in any serious numbers. Even Commodore had probably learned that lesson by then.

Nevertheless, Acorn’s Risc PC was a somewhat credible platform for Unix, if only Acorn hadn’t cancelled their own efforts in that realm. Prominent commentators and enthusiastic developers seized the moment, and with Free Software Unix implementations such as NetBSD and FreeBSD emerging from the shadow of litigation cast upon them, a community effort could be credibly pursued. Linux was also ported to ARM, but such work was actually begun on Acorn’s older A5000 model.

Acorn never seized this opportunity properly, however. Despite entering the network computer market in pursuit of some of Larry Ellison’s billions, expectations of the software in network computers had also increased. After all, networked computers have many of the responsibilities of those sophisticated minicomputers and workstations. But Acorn was still wedded to RISC OS and, for the most part, to ARM. And it ultimately proved that while RISC OS might present quite a nice graphical interface, it was actually NetBSD that could provide the necessary versatility and reliability being sought for such endeavours.

And as the 1990s got underway, the mundane personal computer started needing some of those workstation capabilities, too, eventually erasing the distinction between these two product categories. Tooling up for Unix might have seemed like a luxury, but it had been an exercise in technological necessity. Acorn’s RISC OS had its attractions, notably various user interface paradigms that really should have become more commonplace, together with a scalable vector font system that rendered anti-aliased characters on screen years before Apple or Microsoft managed to, one that permitted the accurate reproduction of those fonts on a dot-matrix printer, a laser printer, and everything in-between.

But the foundations of RISC OS were a legacy from Acorn’s 8-bit era, laid down hastily in an arguably cynical fashion to get the Archimedes out of the door and to postpone the consequences. Commodore inevitably had similar problems with its own legacy software technology, ostensibly more modern than Acorn’s when it was introduced in the Amiga, even having some heritage from another Cambridge endeavour. Acorn might have ported its differentiating technologies to Unix, following the path taken by Torch and its close relative, IXI, also using the opportunity to diversify its hardware options.

In all of this consideration given to Acorn and Commodore, it might seem that Apple, mentioned many paragraphs earlier, has been forgotten. In fact, Apple went through many of the same trials and ordeals as its smaller rivals. Indeed, having made so much money from the Macintosh, Apple’s own attempts to modernise itself and its products involve such a catalogue of projects and initiatives that even summarising them would expand this article considerably.

Only Apple would buy a supercomputer to attempt to devise its own processor architecture – Aquarius – only not to follow through and eventually be rescued by the pair of IBM and Motorola, humbled by an unanticipated decline in their financial and market circumstances. Or have several operating system projects – Opus, Pink, Star Trek, NuKernel, Copland – that were all started but never really finished. Or to get into personal digital assistants with the unfairly maligned Newton, or to consider redesigning the office entirely with its Workspace 2000 collaboration. And yet end up acquiring NeXT, revamping its technologies along that company’s lines, and still barely make it to the end of the decade.

The Final Chapters

Commodore got almost half-way through the 1990s before bankruptcy beckoned. Motorola’s 68060, informed by the work on the chip manufacturer’s abandoned 88000 RISC architecture, provided a considerable performance boost to its more established architecture, even if it now trailed the pack, perhaps only matching previous generations of SPARC and MIPS processors, and now played second fiddle to PowerPC in Motorola’s own line-up.

Acorn’s customers would be slightly luckier. Digital’s StrongARM almost entirely eclipsed ARM’s rather sedate ARM7-based offerings, except in floating-point performance in comparison to a single system-on-chip product, the ARM7500FE. This infusion of new technology was a blessing and a curse for Acorn and its devotees. The Risc PC could not make full use of this performance, and a new machine would be needed to truly make the most of it, also getting a long-overdue update in a range of core industry technologies.

Commodore’s devotees tend to make much of the company’s mismanagement. Deserved or otherwise, one may now be allowed to judge whether the company was truly unique in this regard. As Acorn’s network computer ambitions were curtailed, market conditions became more unfavourable to its increasingly marginalised platform, and the lack of investment in that core platform started to weigh heavily on the company and its customers. A shift in management resulted in a shift in business and yet another endeavour being initiated.

Acorn’s traditional business units were run down, the company’s next generation of personal computer hardware cancelled, and yet a somewhat tangential silicon design business was effectively being incubated elsewhere within the organisation. Meanwhile, Acorn, sitting on a substantial number of shares in ARM, supposedly presented a vulnerability for the latter and its corporate stability. So, a plan was hatched that saw Acorn sold off to a division of an investment bank based in a tax haven, the liberation of its shares in ARM, and the dispersal of Acorn’s assets at rather low prices. That, of course, included the newly incubated silicon design operation, bought by various figures in Acorn’s “senior management”.

Just as Commodore’s demise left customers and distributors seemingly abandoned, so did Acorn’s. While Commodore went through the indignity of rescues and relaunches, Acorn itself disappeared into the realms of anonymous holding companies, surfacing only occasionally in reports of product servicing agreements and other unglamorous matters. Acorn’s product lines were kept going for as long as could be feasible by distributors who had paid for the privilege, but without the decades of institutional experience of an organisation terminated almost overnight, there was never likely to be a glorious resurgence of its computer systems. Its software platform was developed further, primarily for set-top box applications, and survives today more as a curiosity than a contender.

In recent days, efforts have been made by Commodore devotees to secure the rights to trademarks associated with the company, these having apparently been licensed by various holding companies over the years. Various Acorn trademarks were also offloaded to licensors, leading to at least one opportunistic but ill-conceived and largely unwelcome attempt to trade on nostalgia and to cosplay the brand. Whether such attempts might occur in future remains uncertain: Acorn’s legacy intersects with that of the BBC, ARM and other institutions, and there is perhaps more sensitivity about how its trademarks might be used.

In all of this, I don’t want to downplay all of the reasons often given for these companies’ demise, Commodore’s in particular. In reading accounts of people who worked for the company, it is clear that it was not a well-run workplace, with exploitative and abusive behaviour featuring disturbingly regularly. Instead, I wish to highlight the lack of understanding in the communities around these companies and the attribution of success or failure to explanations that do not really hold up.

For instance, the Acorn Electron may have consumed many resources in its development and delivery, but it did not lead to Acorn’s “downfall”, as was claimed by one absurd comment I read recently. Acorn’s rescue by Olivetti was the consequence of several other things, too, including an ill-advised excursion into the US market, an attempt to move upmarket with an inadequate product range, some curious procurement and logistics practices, and a lack of capital from previous stock market flotations. And if there had been such a “downfall”, such people would not be piping up constantly about ARM being “the chip in everyone’s phone”, which is tiresomely fashionable these days. ARM may well have been just a short footnote in some dry text about processor architectures.

In these companies, some management decisions may have made sense, while others were clearly ill-considered. Similarly, those building the products could only do so much given the technological choices that had already been made. But more intriguing than the actual intrigues of business is to consider what these companies might have learned from each other, what the product developers might have borrowed from each other had they been able to, and what they might have achieved had they been able to collaborate somehow. Instead, both companies went into decline and ultimately fell, divided by the barriers of competition.

Update: It seems that the chart did not have the correct value for the Amiga 4000/040, due to a missing conversion from VAX MIPS to something resembling the original Dhrystone score. Thus, in integer performance as measured by this benchmark, the 68040 at 25MHz was broadly comparable to the R3000 at 25MHz, but was also already slipping behind faster R3000 parts even before the SuperSPARC and R4000 emerged.