Pessimistic perspectives on technological sustainability

Tuesday, August 16th, 2022I was recently perusing the Retro Computing Forum when I stumbled across a mention of Collapse OS. If your anxiety levels have not already been maxed out during the last few years of climate breakdown, psychological warfare, pandemic, and actual warmongering, accompanied by supply chain breakdowns, initially in technology and exacerbated by overconsumption and spivcoin, now also in commodities and exacerbated by many of those other factors (particularly the warmongering), then perhaps focusing on societal and civilisational collapse isn’t going to improve your mood or your outlook. Unusually, then, after my last, rather negative post on such topics, may I be the one to introduce some constructive input and perhaps even some slight optimism?

If I understand the motivations behind Collapse OS correctly, it is meant to provide a modest computing environment that can work on well-understood, commonplace, easily repaired and readily sourced hardware, with the software providing the environment itself being maintainable on the target hardware, as opposed to being cross-built on more powerful hardware and then deployed to simpler, less capable hardware. The envisaged scenario for its adoption is a world where powerful new hardware is no longer produced or readily available and where people must scavenge and “make do” with the hardware already produced. Although civilisation may have brought about its own collapse, the consolation is that so much hardware will have been strewn across the planet for a variety of purposes that even after semiconductor fabrication and sophisticated manufacturing have ceased, there will remain a bounty of hardware usable for people’s computational needs (whatever they may be).

I am not one to try and predict the future, and I don’t really want to imagine it as being along the same lines as the plot for one of Kevin Costner’s less successful movies, either, but I feel that Collapse OS and its peers, in considering various dystopian scenarios and strategies to mitigate their impacts, may actually offer more than just a hopefully sufficient kind of preparedness for a depressing future. In that future, without super-fast Internet, dopamine-fired social media, lifelike gaming, and streaming video services with huge catalogues of content available on demand, everyone has to accept that far less technology will be available to them: they get no choice in the matter. Investigating how they might manage is at the very least an interesting thought experiment. But we would be foolish to consider such matters as purely part of a possible future and not instructive in other ways.

An Overlap of Interests

As readers of my previous articles will be aware, I have something of an interest in older computers, open source hardware, and sustainable computing. Older computers lend themselves to analysis and enhancement even by individuals with modest capabilities and tools because they employ technologies that may have been regarded as “miniaturised” when they were new, but they were still amenable to manual assembly and repair. Similarly, open source hardware has grown to a broad phenomenon because the means to make computing systems and accessories has now become more accessible to individuals, as opposed to being the preserve of large and well-resourced businesses. Where these activities experience challenges, it is typically in the areas that have not yet become quite as democratised, such as semiconductor fabrication at the large-scale integration level, along with the development and manufacture of more advanced technology, such as components and devices that would be competitive with off-the-shelf commercial products.

Some of the angst around open source hardware concerns the lack of investment it receives from those who would benefit from it, but much of that investment would largely be concerned with establishing an ability to maintain some kind of parity with modern, proprietary hardware. Ignoring such performance-led requirements and focusing on simpler hardware projects, as many people already do, brings us a lot closer to retrocomputing and a lot closer to the constrained hardware scenario envisaged by Collapse OS. My own experiments with PIC32-based microcontrollers are not too far removed from this, and it would not be inconceivable to run a simple environment in the 64K of RAM and 256K of flash memory of the PIC32MX270, this being much more generous than many microcomputers and games consoles of the 1980s.

Although I relied on cross-compilation to build the programs that would run on the minimal hardware of the PIC32 microcontroller, Collapse OS emphasises self-hosting: that it is possible to build the software within the running software itself. After all, how sustainable would a frugal computing environment be if it needed a much more powerful development system to fix and improve it? For Collapse OS, such self-hosting is enabled by the use of the Forth programming language, as explained by the rationale for switching to Forth from a system implemented in assembly language. Such use of Forth is not particularly unusual: its frugal demands were prized in the microcomputer era and earlier, with its creator Charles Moore describing the characteristics of a computer designed to run Forth as needing around 8K of RAM and 8K of ROM, this providing a complete interactive system.

(If you are interested in self-hosting and bootstrapping, one place to start might be the bootstrapping wiki.)

For a short while, Forth was perhaps even thought to be the hot new thing in some circles within computing. One fairly famous example was the Jupiter Ace microcomputer, developed by former Sinclair Research designers, offering a machine that followed on fairly closely from Sinclair’s rudimentary ZX81. But in a high-minded way one might have expected from the Sinclair stable and the Cambridge scene, it offered Forth as its built-in language in response to all the other microcomputers offering “unstructured” BASIC dialects. Worthy as such goals might have been, the introduction of a machine with outdated hardware specifications condemned it in its target market as a home computer, with it offering primitive black-and-white display output against competitors offering multi-colour graphics, and offering limited amounts of memory as competitors launched with far more fitted as standard. Interestingly, the Z80 processor at the heart of the Ace was the primary target of Collapse OS, and one might wonder if the latter might actually be portable to the former, which would be an interesting project if any hardware collector wants to give it a try!

Other Forth-based computers were delivered such as the Canon Cat: an unusual “information appliance” that might have formed the basis of Apple’s Macintosh had that project not been diverted towards following up on the Apple Lisa. Dedicated Forth processors were even delivered, as anticipated already by Moore back in 1980, reminiscent of the Lisp machine era. However, one hardware-related legacy of Forth is that of the Open Firmware standard where a Forth environment provides an interactive command-line interface to a system’s bootloader. Collapse OS fits in pretty well with that kind of application of Forth. Curiously, someone did contact me when I first wrote about my PIC32 experiments, this person maintaining their own microcontroller Forth implementation, and in the context of this article I have re-established contact because I never managed to properly follow up on the matter.

Changing the Context

According to a broad interpretation of the Collapse OS hardware criteria, the PIC32MX270 would actually not be a bad choice. Like the AVR microcontrollers and the microprocessors of the 1980s, PIC32MX microcontrollers are available in convenient dual in-line packages, but unlike those older microprocessors they also offer the 32-bit MIPS architecture that is nicer to program than the awkward instruction sets of the likes of the Z80 and 6502, no matter how much nostalgia colours people’s preferences. However, instead of focusing on hardware suitability in a resource-constrained future, I want to consider the messages of simplicity and sustainability that underpin the Collapse OS initiative and might be relevant to the way we practise computing today.

When getting a PIC32 microcontroller to produce a video signal, part of the motivation was just to see how straightforward it might be to make a simple “single chip” microcomputer. Like many microcomputers back in the 1980s, it became tempting to consider how it might be used to deliver graphical demonstrations and games, but I also wondered what kind of role such a system might have in today’s world. Similar projects, including the first versions of the Maximite have emphasised such things as well, along with interfacing and educational applications (such as learning BASIC). Indeed, many low-end microcontroller-based computers attempt to recreate and to emphasise the sparse interfaces of 1980s microcomputers as a distraction-free experience for learning and teaching.

Eliminating distractions is a worthy goal, whether those distractions are things that we can conveniently seek out when our attention wanders, such as all our favourite, readily accessible Internet content, or whether they come in the form of the notifications that plague “modern” user interfaces. Another is simply reducing the level of consumption involved in our computational activities: civilisational collapse would certainly impose severe limits on that kind of consumption, but it would seem foolish to acknowledge that and then continue on the same path of ever-increasing consumption that also increasingly fails to deliver significant improvements in the user experience. When desktop applications, mobile “apps”, and Web sites frequently offer sluggish and yet overly-simplistic interfaces that are more infuriating than anything else, it might be wise to audit our progress and reconsider how we do certain things.

Human nature has us constantly exploring the boundaries of what is possible with technology, but some things which captivate people at any given point on the journey of technological progress may turn out to be distracting diversions from the route ultimately taken. In my trawl of microcomputing history over the last couple of years, I was reminded of an absurd but illustrative example of how certain technological exercises seem to become the all-consuming focus of several developers, almost being developed for the sake of it, before the fad in question flames out and everybody moves on. That example concerned “morphing” software, inspired by visual effects from movies such as Terminator 2, but operating on a simpler, less convincing level.

Suddenly, such effects were all over the television and for a few months in late 1993, everyone was supposedly interested in making the likeness of one famous person slowly change into the likeness of another, never mind that it really required a good library of images, this being somewhat before widespread digital imaging and widespread image availability. Fast-forward a few years, and it all seemed like a crazy mass delusion best never spoken of again. We might want to review our own time’s obsessions with performative animations and effects, along with the peculiarities of touch-based interfaces, the assumption of pervasive and fast connectivity, and how these drive hardware consumption and obsolescence.

Once again, some of this comes back to asking how people managed to do things in earlier times and why things sometimes seem so complicated now. Thinking back to the 1980s era of microcomputing, my favourite 8-bit computer of those times was the Acorn Electron, this being the one I had back then, and it was certainly possible to equip it to do word processing to a certain level. Acorn even pitched an expanded version as a messaging terminal for British Telecom, although I personally think that they could have made more of such opportunities, especially given the machine’s 80-column text capabilities being made available at such a low price. The user experience would not exactly be appealing by today’s standards, but then nor would that of Collapse OS, either.

When I got my PIC32 experiment working reasonably, I asked myself if it would be sufficient for tasks like simple messaging and writing articles like this. The answer, assuming that I would enhance that effort to use a USB keyboard and external storage, is probably the same as whether anyone might use a Maximite for such applications: it might not be as comfortable as on a modern system but it would be possible in some way. Given the tricks I used, certain things would actually be regressions from the Electron, such as the display resolution. Conversely, the performance of a 48MHz MIPS-based processor is obviously going to be superior to a 2MHz 6502, even when having to generate the video signal, thus allowing for some potential in other areas.

Reversing Technological Escalation

Using low-specification hardware for various applications today, considering even the PIC32 as low-spec and ignoring the microcomputers of the past, would also need us to pare back the demands that such applications have managed to accumulate over the years. As more powerful, higher-performance hardware has become available, software, specifications and standards have opportunistically grown to take advantage of that extra power, leaving many people bewildered by the result: their new computer being just as slow as their old one, for example.

Standards can be particularly vulnerable where entrenched interests drive hardware consumption whilst seeking to minimise the level of adaptation their own organisations will need to undertake in order to deliver solutions based on such standards. A severely constrained computing device may not have the capacity or performance to handle all the quirks of a “full fat” standard, but it might handle an essential core of that standard, ignoring all the edge cases and special treatment for certain companies’ products. Just as important, the developers of an implementation handling a standard also may not have the capacity or tenacity for a “full fat” standard, but they may do a reasonable job handling one that cuts out all the corporate cruft.

And beyond the technology needed to perform some kind of transaction as part of an activity, we might reconsider what is necessary to actually perform that activity. Here, we may consider the more blatant case of the average “modern” Web site or endpoint, where an activity may end up escalating and involving the performance of a number of transactions, many of which superfluous and, in the case of the pervasive cult of analytics, exploitative. What once may have been a simple Web form is often now an “experience” where the browser connects to dozens of sites, where all the scripts poll the client computer into oblivion, and where the functionality somehow doesn’t manage to work, anyway (as I recently experienced on one airline’s Web site).

Technologists and their employers may drive consumption, but so do their customers. Public institutions, utilities and other companies may lazily rely on easily procured products and services, these insisting (for “security” or “the best experience”) that only the latest devices or devices from named vendors may be used to gain access. Here, the opposite of standardisation occurs, where adherence to brand names dictates the provision of service, compounded by the upgrade treadmill familiar from desktop computing, bringing back memories of Microsoft and Intel ostensibly colluding to get people to replace their computer as often as possible.

A Broader Brush

We don’t need to go back to retrocomputing levels of technology to benefit from re-evaluating the prevalent technological habits of our era. I have previously discussed single-board computers like the MIPS Creator CI20 which, in comparison to contemporary boards from the Raspberry Pi series, was fairly competitive in terms of specification and performance (having twice the RAM of the Raspberry Pi Models A+, B and B+). Although hardly offering conventional desktop performance upon its introduction, the CI20 would have made a reasonable workstation in certain respects in earlier times: its 1GHz CPU and 1GB of RAM should certainly be plenty for many applications even now.

Sadly, starting up and using the main two desktop environments on the CI20 is an exercise in patience, and I recommend trying something like the MATE desktop environment just for something responsive. Using a Web browser like Firefox is a trial, and extensive site blocking is needed just to prevent the browser wanting to download things from all over the place, as it tries to do its bit in shoring up Google’s business model. My father was asking me the other day why a ten-year-old computer might be slow on a “modern” Web site but still perfectly adequate for watching video. I would love to hear the Firefox and Chrome developers, along with the “architects of the modern Web”, give any explanation for this that doesn’t sound like they are members of some kind of self-realisation cult.

If we can envisage a microcomputer, either a vintage one or a modern microcontroller-based one, performing useful computing activities, then we can most certainly envisage machines of ten or so years ago, even ones behind the performance curve, doing so as well. And by realising that, we might understand that we might even have the power to slow down the engineered obsolescence of computing hardware, bring usable hardware back into use, and since not everyone on the planet can afford the latest and greatest, we might even put usable hardware into the hands of more people who might benefit from it.

Naturally, this perspective is rather broader than one that only considers a future of hardship and scarcity, but hardship and scarcity are part of the present, just as they have always been part of the past. Applying many of the same concerns and countermeasures to today’s situation, albeit in less extreme forms, means that we have the power to mitigate today’s situation and, if we are optimistic, perhaps steer it away from becoming the extreme situation that the Collapse OS initiative seeks to prepare for.

Concrete Steps

I have, in the past, been accused of complaining about injustices too generally for my complaints to be taken seriously, never mind such injustices being blatant and increasingly obvious in our modern societies and expressed through the many crises of our times. So how might we seek to mitigate widespread hardware obsolescence and technology-driven overconsumption? Some suggestions in a concise list for those looking for actionable things:

- Develop, popularise and mandate lightweight formats, protocols and standards

- Encourage interoperability and tolerance for multiple user interfaces, clients and devices

- Insist on an unlimited “right to repair” for computing devices including the software

- Encourage long-term thinking in software and systems development

And now for some elucidation…

Mandatory Accessible Standards

This suggestion has already been described above, but where it would gain its power is in the idea of mandating that public institutions and businesses would be obliged to support lightweight formats, protocols and standards, and not simply as an implementation detail for their chosen “app”, like a REST endpoint might be, but actually as a formal mechanism providing service to those who would interact with those institutions. This would make the use of a broad range of different devices viable, and in the case of special-purpose devices for certain kinds of users, particularly those who would otherwise be handed a smartphone and told to “get with it”, it would offer a humane way of accessing services that is currently denied to them.

For simple dialogue-based interactions, existing formats such as JSON might even be sufficient as they are. I am reminded of a paper I read when putting together my degree thesis back in the 1990s, where the idea was that people would be able to run programs safely in their mail reader, with one example being that of submitting forms.

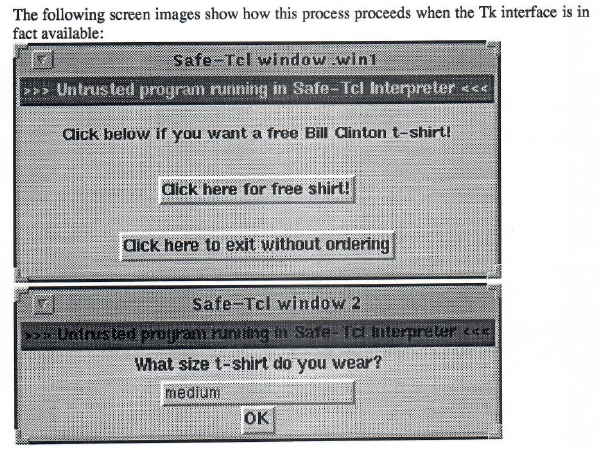

T-shirt ordering dialogues shown by Safe-Tcl running in a mail program, offering the recipient the chance to order some merchandise that might not be as popular now.

In that paper, most of the emphasis was on the safety of the execution environment as opposed to the way in which the transaction was to be encoded, but it is not implausible that one might have encoded the details of the transaction – the T-shirt size (with the recipient’s physical address presumably already being known to the sender) – in a serialised form of the programming language concerned (Safe-Tcl) as opposed to just dumping some unstructured text in the body of a mail. I would need to dig out my own thesis to see what ideas I had for serialised information. Certainly, such transactions even embellished with other details and choices and with explanatory information, prompts and questions do not require megabytes of HTML, CSS, JavaScript, images, videos and so on.

Interoperability and Device Choice

One thing that the Web was supposed to liberate us from was the insistence that to perform a particular task, we needed a particular application, and that particular application was only available on a particular platform. In the early days, HTML was deliberately simplistic in its display capabilities, and people had to put up with Web pages that looked very plain until things like font tags allowed people to go wild. With different factions stretching HTML in all sorts of directions, CSS was introduced to let people apply presentation attributes to documents, supposedly without polluting or corrupting the original HTML that would remain semantically pure. We all know how this turned out, particularly once the Web 2.0 crowd got going.

Back in the 1990s, I worked on an in-house application at my employer that used a document model inspired by SGML (as HTML had been), and the graphical user interface to the documents being exchanged initially offered a particular user interface paradigm when dealing with collections of data items, this being the one embraced by the Macintosh’s Finder when showing directory hierarchies in what we would now call a tree view. Unfortunately, users seemed to find expanding and hiding things by clicking on small triangles to be annoying, and so alternative presentation approaches were explored. Interestingly, the original paradigm would be familiar even now to those using generic XML editor software, but many people would accept that while such low-level editing capabilities are nice to have, higher-level representations of the data are usually much more preferable.

Such user preferences could quite easily be catered to through the availability of client software that works in the way they expect, rather than the providers of functionality or the operators of services trying to gauge what the latest fashions in user interfaces might be, as we have all seen when familiar Web sites change to mimic something one would expect to see on a smartphone, even with a large monitor on a desk with plenty of pixels to spare. With well-defined standards, if a client device or program were to see that it needed to allow a user to peruse a large collection of items or to choose a calendar date, it would defer to the conventions of that device or platform, giving the user the familiarity they expect.

This would also allow clients and devices with a wide range of capabilities to be used. The Web tried to deliver a reasonable text-only experience for a while, but most sites can hardly be considered usable in a textual browser these days. And although there is an “accessibility story” for the Web, it largely appears to involve retrofitting sites with semantic annotations to help users muddle through the verbose morass encoded in each page. Certainly, the Web of today does do one thing reasonably by mixing up structure and presentation: it can provide a means of specifying and navigating new kinds of data that might be unknown to the client, showing them something more than a text box. A decent way of extending the range of supported data types would be needed in any alternative, but it would need to spare everyone suddenly having scripts running all over the place.

Rights to Repair

The right to repair movement has traditionally been focused on physical repairs to commercial products, making sure that even if the manufacturer has abandoned a product and really wants you to buy something new from them, you can still choose to have the product repaired so that it can keep serving you well for some time to come. But if hardware remains capable enough to keep doing its job, and if we are able to slow down or stop the forces of enforced obsolescence, we also need to make sure that the software running on the hardware may also be repaired, maintained and updated. A right to repair very much applies to software.

Devotees of the cult of the smartphone, those who think that there is an “app” for everything, should really fall silent with shame. Not just for shoehorning every activity they can think of onto a device that is far from suitable for everyone, and not just for mandating commercial relationships with large multinational corporations for everyone, but also for the way that happily functioning smartphones have to be discarded because they run software that is too old and cannot be fixed or upgraded. Demanding the right to exercise the four freedoms of Free Software for our devices means that we get to decide when those devices are “too old” for what we want to use them for. If a device happens to be no longer usable for its original activity even after some Free Software repairs, we can repurpose it for something else, instead of having the vendor use those familiar security scare stories and pretending that they are acting in our best interests.

Long-Term Perspectives

If we are looking to preserve the viability of our computing devices by demanding interoperability to give them a chance to participate in the modern world and by demanding that they may be repaired, we also need to think about how the software we develop may itself remain viable, both in terms of the ability to run the software on available devices as well as the ability to keep maintaining, improving and repairing it. That potentially entails embracing unfashionable practices because “modern” practices do not exactly seem conducive to the kind of sustainable activities we have in mind.

I recently had the opportunity to contemplate the deployment of software in “virtual environments” containing entire software stacks, each of which running their own Web server program, that would receive their traffic from another Web server program running in the same virtual machine, all of this running in some cloud infrastructure. It was either that or using containers containing whole software distributions, these being deployed inside virtual machines containing their own software distributions. All because people like to use the latest and greatest stuff for everything, this stuff being constantly churned by fashionable development methodologies and downloaded needlessly over and over again from centralised Internet services run by monopolists.

Naturally, managing gigabytes of largely duplicated software is worlds, if not galaxies, away from the modest computing demands of things like Collapse OS, but it would be distasteful to anyone even a decade ago and shocking to anyone even a couple of decades ago. Unfashionable as it may seem now, software engineering courses once emphasised things like modularity and the need for formal interfaces between modules in systems. And a crucial benefit of separating out functionality into modules is to allow those modules to mature, do the job they were designed for, and to recede into the background and become something that can be relied upon and not need continual, intensive maintenance. There is almost nothing better than writing a library that one may use constantly but never need to touch again.

Thus, the idea that a precarious stack of precisely versioned software is required to deliver a solution is absurd, but it drives the attitude that established software distributions only deliver “old” software, and it drives the demand for wasteful container or virtual environment solutions whose advocates readily criticise traditional distributions whilst pilfering packages from them. Or as Docker users might all too easily say, “FROM debian:sid”. Part of the problem is that it is easy to rely on methods of mass consumption to solve problems with software – if something is broken, just update and see if it fixes it – but such attitudes permeate the entire development process, leading to continual instability and a software stack constantly in flux.

Dealing with a multitude of software requirements is certainly a challenging problem that established operating systems struggle to resolve convincingly, despite all the shoehorning of features into the Linux technology stack. Nevertheless, the topic of operating system design is rather outside the scope of this article. Closer to relevance is the matter of how people seem reluctant to pick a technology and stick with it, particularly in the realm of programming languages. Then again, I covered much of this before and fairly recently, too. Ultimately, we want to be establishing software stacks that people can readily acquaint themselves with decades down the line, without the modern-day caveats that “feature X changed in version Y” and that if you were not there at the time, you have quite the job to do to catch up with that and everything else that went on, including migrations to a variety of source management tools and venues, maybe even completely new programming languages.

A Different Mindset

If anything, Collapse OS makes us consider a future beyond tomorrow, next week, next year, or a few years’ time. Even if the wheels do not start falling off the vehicle of human civilisation, there are still plenty of other things that can go away without much notice. Corporations like Apple and Google might stick around, whether that is good news or not, but it does not stop them from pulling the plug on products and services. Projects and organisations do not always keep going forever, not least because they are often led by people who cannot keep going forever, either.

There are ways we can mitigate these threats to sustainability and longevity, however. We can share our software through accessible channels without insisting that others use those monopolist-run centralised hosting services. We can document our software so that others have a chance of understanding what we were thinking when we wrote it. We can try and keep the requirements for our software modest and give people a chance to deploy it on modest hardware. And we might think about what kind of world we are leaving behind and whether it is better than the world we were born into.