One Step Forward, Two Steps Back

Thursday, August 10th, 2017I have written about the state of “The Free Software Desktop” before, and how change apparently for change’s sake has made it difficult for those of us with a technology background to provide a stable and reliable computing experience to others who are less technically inclined. It surprises me slightly that I have not written about this topic more often, but the pattern of activity usually goes something like this:

- I am asked to upgrade or troubleshoot a computer running a software distribution I have indicated a willingness to support.

- I investigate confusing behaviour, offer advice on how to perform certain tasks using the available programs, perhaps install or upgrade things.

- I get exasperated by how baroque or unintuitive the experience must be to anyone not “living the dream” of developing software for one of the Free Software desktop environments.

- Despite getting very annoyed by the lack of apparent usability of the software, promising myself that I should at least mention how frustrating and unintuitive it is, I then return home and leave things for a few days.

- I end up calming down sufficiently about the matter to not to be so bothered about saying something about it after all.

But it would appear that this doesn’t really serve my interests that well because the situation apparently gets no better as time progresses. Back at the end of 2013, it took some opining from a community management “expert” to provoke my own commentary. Now, with recent experience of upgrading a system between Kubuntu long-term support releases, I feel I should commit some remarks to writing just to communicate my frustration while the experience is still fresh in my memory.

Back in 2013, when I last wrote something on the topic, I suppose I was having to manage the transition of Kubuntu from KDE 3 to KDE 4 on another person’s computer, perhaps not having to encounter this yet on my own Debian system. This transition required me to confront the arguably dubious user interface design decisions made for KDE 4. I had to deal with things like the way the desktop background no longer behaved as it had done on most systems for many years, requiring things like the “folder view” widget to show desktop icons. Disappointingly, my most recent experience involved revisiting and replaying some of these annoyances.

Actual Users

It is worth stepping back for a moment and considering how people not “living the dream” actually use computers. Although a desktop cluttered with icons might be regarded as the product of an untidy or disorganised user, like the corporate user who doesn’t understand filesystems and folders and who saves everything to the desktop just to get through the working day, the ability to put arbitrary icons on the desktop background serves as a convenient tool to present a range of important tasks and operations to less confident and less technically-focused users.

Let us consider the perspective of such users for a moment. They may not be using the computer to fill their free time, hang out online, or whatever the kids do these days. Instead, they may have a set of specific activities that require the use of the computer: communicate via e-mail, manage their photographs, read and prepare documents, interact with businesses and organisations.

This may seem quaint to members of the “digital native” generation for whom the interaction experience is presumably a blur of cloud service interactions and social media posts. But unlike the “digital natives” who, if you read the inevitably laughable articles about how today’s children are just wizards at technology and that kind of thing, probably just want to show their peers how great they are, there are also people who actually need to get productive work done.

So, might it not be nice to show a few essential programs and actions as desktop icons to direct the average user? I even had this set up having figured out the “folder view” widget which, as if embarrassed at not having shown up for work in the first place, actually shows the contents of the “Desktop” directory when coaxed into appearing. Problem solved? Well, not forever. (Although there is a slim chance that the problem will solve itself in future.)

The Upgrade

So, Kubuntu had been moaning for a while about a new upgrade being available. And being the modern way with KDE and/or Ubuntu, the user is confronted with parade after parade of notifications about all things important, trivial, and everything in between. Admittedly, it was getting to the point where support might be ending for the distribution version concerned, and so the decision was taken to upgrade. In principle this should improve the situation: software should be better supported, more secure, and so on. Sadly, with Ubuntu being a distribution that particularly likes to rearrange the furniture on a continuous basis, it just created more “busy work” for no good reason.

To be fair, the upgrade script did actually succeed. I remember trying something similar in the distant past and it just failing without any obvious remedy. This time, there were some messages nagging about package configuration changes about which I wasn’t likely to have any opinion or useful input. And some lengthy advice about reconfiguring the PostgreSQL server, popping up in some kind of packaging notification, seemed redundant given what the script did to the packages afterwards. I accept that it can be pretty complicated to orchestrate this kind of thing, though.

It was only afterwards that the problems began to surface, beginning with the login manager. Since we are describing an Ubuntu derivative, the default login manager was the Unity-styled one which plays some drum beats when it starts up. But after the upgrade, the login manager was obsessed with connecting to the wireless network and wouldn’t be denied the chance to do so. But it also wouldn’t connect, either, even if given the correct password. So, some work needed to be done to install a different login manager and to remove the now-malfunctioning software.

An Empty Desk

Although changing the login manager also changes the appearance of the software and thus the experience of using it, providing an unnecessary distraction from the normal use of the machine and requiring unnecessary familiarisation with the result of the upgrade, at least it solved a problem of functionality that had “gone rogue”. Meanwhile, the matter of configuring the desktop experience has perhaps not yet been completely and satisfactorily resolved.

When the machine in question was purchased, it was running stock Ubuntu. At some point, perhaps sooner rather than later, the Unity desktop became the favoured environment getting the attention of the Ubuntu developers, and finding that it was rather ill-suited for users familiar with more traditional desktop paradigms, a switch was made to the KDE environment instead. This is where a degree of peace ended up being made with the annoyingly disruptive changes introduced by KDE 4 and its Plasma environment.

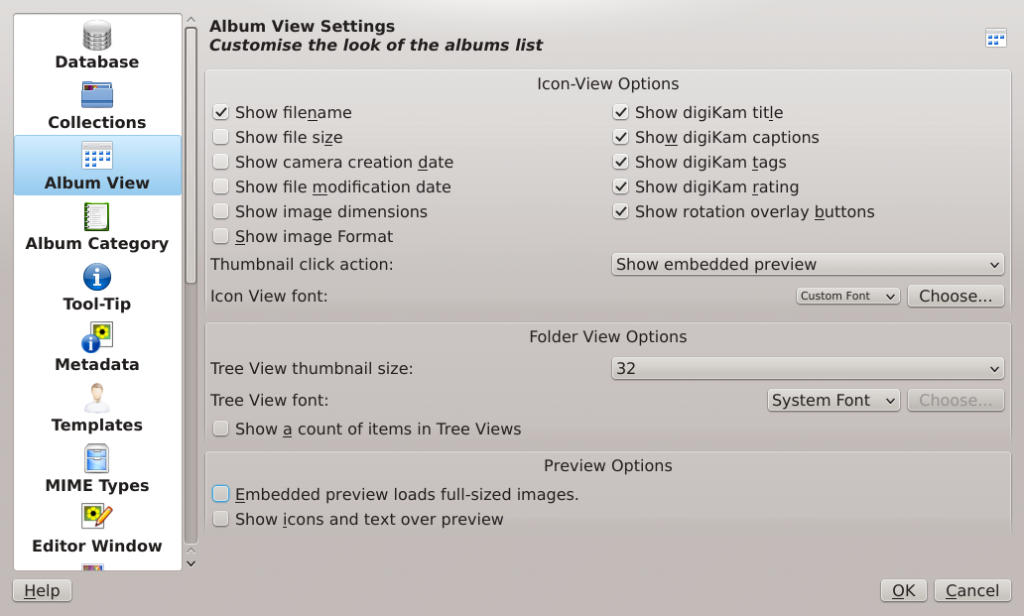

One problem that KDE always seems to have had is that of respecting user preferences and customisations across upgrades. On this occasion, with KDE Plasma 5 now being offered, no exception was made: logging in yielded no “folder view” widgets with all those desktop icons; panels were bare; the desktop background was some stock unfathomable geometric form with blurry edges. I seem to remember someone associated with KDE – maybe even the aforementioned “expert” – saying how great it had been to blow away his preferences and experience the awesomeness of the raw experience, or something. Well, it really isn’t so awesome if you are a real user.

As noted above, persuading the “folder view” widgets to return was easy enough once I had managed to open the fancy-but-sluggish widget browser. This gave me a widget showing the old icons that was too small to show them all at once. So, how do you resize it? Since I don’t use such features myself, I had forgotten that it was previously done by pointing at the widget somehow. But because there wasn’t much in the way of interactive help, I had to search the Web for clues.

This yielded the details of how to resize and move a folder view widget. That’s right: why not emulate the impoverished tablet/phone interaction paradigm and introduce a dubious “long click” gesture instead? Clearly because a “mouseover” gesture is non-existent in the tablet/phone universe, it must be abolished elsewhere. What next? Support only one mouse button because that is how the Mac has always done it? And, given that context menus seem to be available on plenty of other things, it is baffling that one isn’t offered here.

Restoring the desktop icons was easy enough, but showing them all was more awkward because the techniques involved are like stepping back to an earlier era where only a single control is available for resizing, where combinations of moves and resizes are required to get the widget in the right place and to be the right size. And then we assume that the icons still do what they had done before which, despite the same programs being available, was not the case: programs didn’t start but also didn’t give any indication why they didn’t start, this being familiar to just about anyone who has used a desktop environment in the last twenty years. Maybe there is a log somewhere with all the errors in it. Who knows? Why is there never any way of troubleshooting this?

One behaviour that I had set up earlier was single-click activation of icons, where programs could be launched with a single click with the mouse. That no longer works, nor is it obvious how to change it. Clearly the usability police have declared the unergonomic double-click action the “winner”. However, some Qt widgets are still happy with single-click navigation. Try explaining such inconsistencies to anyone already having to remember how to distinguish between multiple programs, what each of them does and doesn’t do, and so on.

The Developers Know Best

All of this was frustrating enough, but when trying to find out whether I could launch programs from the desktop or whether such actions had been forbidden by the usability police, I found that when programs were actually launching they took a long time to do so. Firing up a terminal showed the reason for this sluggishness: Tracker and Baloo were wanting to index everything.

Despite having previously switched off KDE’s indexing and searching features and having disabled, maybe even uninstalled, Tracker, the developers and maintainers clearly think that coercion is better than persuasion, that “everyone” wants all their content indexed for “desktop search” or “semantic search” (or whatever they call it now), the modern equivalent of saving everything to the desktop and then rifling through it all afterwards. Since we’re only the stupid users, what would we really have to say about it? So along came Tracker again, primed to waste computing time and storage space, together with another separate solution for doing the same thing, “just in case”, because the different desktop developers cannot work together.

Amongst other frustrations, the process of booting to the login prompt is slower, and so perhaps switching from Upstart to systemd wasn’t such an entirely positive idea after all. Meanwhile, with reduced scrollbar and control affordances, it would seem that the tendency to mimic Microsoft’s usability disasters continues. I also observed spontaneous desktop crashes and consequently turned off all the fancy visual effects in order to diminish the chances of such crashes recurring in future. (Honestly, most people don’t want Project Looking Glass and similar “demoware” guff: they just want to use their computers.)

Of Entitlement and Sustainable Development

Some people might argue that I am just another “entitled” user who has never contributed anything to these projects and is just whining incorrectly about how bad things are. Well, I do not agree. I enthusiastically gave constructive feedback and filed bugs while I still believed that the developers genuinely wanted to know how they might improve the software. (Admittedly, my enthusiasm had largely faded by the time I had to migrate to KDE 4.) I even wrote software using some of the technologies discussed in this article. I always wanted things to be better and stuck with the software concerned.

And even if I had never done such things, I would, along with other users, still have invested a not inconsiderable amount of effort into familiarising people with the software, encouraging others to use it, and trying to establish it as a sustainable option. As opposed to proprietary software that we neither want to use, nor wish to support, nor are necessarily able to support. Being asked to support some Microsoft product is not only ethically dubious but also frustrating when we end up having to guess our way around the typically confusing and poorly-designed interfaces concerned. And we should definitely resent having to do free technical support for a multi-billion-dollar corporation even if it is to help out other people we know.

I rather feel that the “entitlement” argument comes up when both the results of the development process and the way the development is done are scrutinised. There is this continually perpetuated myth that “open source” can only be done by people when those people have “enough time and interest to work on it”, as if there can be no other motivations or models to sustain the work. This cultivates the idea of the “talented artist” developer lifestyle: that the developers do their amazing thing and that its proliferation serves as some form of recognition of its greatness; that, like art, one should take it or leave it, and that the polite response is to applaud it or to remain silent and not betray a supposed ignorance of what has been achieved.

I do think that the production of Free Software is worthy of respect: after all, I am a developer of Free Software myself and know what has to go into making potentially useful systems. But those producing it should understand that people depend on it, too, and that the respect its users have for the software’s development is just as easily lost as it is earned, indeed perhaps more easily lost. Developers have power over their users, and like anyone in any other position of power, we expect them to behave responsibly. They should also recognise that any legitimate authority they have over their users can only exist when they acknowledge the role of those users in legitimising and validating the software.

In a recent argument about the behaviour of systemd, its principal developer apparently noted that as Free Software, it may be forked and developed as anyone might wish. Although true, this neglects the matter of sustainable software development. If I disagree with the behaviour of some software or of the direction of a software project, and if there is no reasonable way to accommodate this disagreement within the framework of the project, then I must maintain my own fork of that software indefinitely if I am to continue using it.

If others cannot be convinced to participate in this fork, and if other software must be changed to work with the forked code, then I must also maintain forks of other software packages. Suddenly, I might be looking at having to maintain an entire parallel software distribution, all because the developers of one piece of software are too precious to accept other perspectives as being valid and are unwilling to work with others in case it “compromises their vision”, or whatever.

Keeping Up on the Treadmill

Most people feel that they have no choice but to accept the upgrade treadmill, the constant churn of functionality, the shiny new stuff that the developers “living the dream” have convinced their employers or their peers is the best and most efficient way forward. It just isn’t a practical way of living for most users to try and deal with the consequences of this in a technical fashion by trying to do all those other people’s jobs again so that they may be done “properly”. So that “most efficient way” ends up incurring inefficiencies and costs amongst everybody else as they struggle to find new ways of doing the things that just worked before.

How frustrating it is that perhaps the only way to cope might be to stop using the software concerned altogether! And how unfortunate it is that for those who do not value Free Software in its own right or who feel that the protections of Free Software are unaffordable luxuries, it probably means that they go and use proprietary software instead and just find a way of rationalising the decision and its inconvenient consequences as part of being a modern consumer engaging in yet another compromised transaction.

So, unhindered by rants like these and by more constructive feedback, the Free Software desktop seems to continue on its way, seemingly taking two steps backward for every one step forward, testing the tolerance even of its most patient users to disruptive change. I dread having to deal with such things again in a few years’ time or even sooner. Maybe CDE will once again seem like an attractive option and bring us full circle for “Unix on the desktop”, saving many people a lot of unnecessary bother. And then the tortoise really will have beaten the hare.