Replaying the Microcomputing Revolution

Monday, January 6th, 2025Since microcomputing and computing history are particular topics of interest of mine, I was naturally engaged by a recent article about the Raspberry Pi and its educational ambitions. Perhaps obscured by its subsequent success in numerous realms, the aspirations that originally drove the development of the Pi had their roots in the effects of the introduction of microcomputers in British homes and schools during the 1980s, a phenomenon that supposedly precipitated a golden age of hands-on learning, initiating numerous celebrated and otherwise successful careers in computing and technology.

Such mythology has the tendency to greaten expectations and deepen nostalgia, and when society enters a malaise in one area or another, it often leads to efforts to bring back the magic through new initiatives. Enter the Raspberry Pi! But, as always, we owe it to ourselves to step through the sequence of historical events, as opposed to simply accepting the narratives peddled by those with an agenda or those looking for comforting reminders of their own particular perspectives from an earlier time.

The Raspberry Pi and other products, such as the BBC Micro Bit, associated with relatively recent educational initiatives, were launched with the intention of restoring the focus of learning about computing to that of computing and computation itself. Once upon a time, computers were largely confined to large organisations and particular kinds of endeavour, generally interacting only indirectly with wider society. Thus, for most people, what computers were remained an abstract notion, often coupled with talk of the binary numeral system as the “language” of these mysterious and often uncompromising machines.

However, as microcomputers emerged both in the hobbyist realm – frequently emphasised in microcomputing history coverage – and in commercial environments such as shops and businesses, governments and educators identified a need for “computer literacy”. This entailed practical experience with computers and their applications, informed by suitable educational material, enabling the broader public to understand the limitations and the possibilities of these machines.

Although computers had already been in use for decades, microcomputing diminished the cost of accessible computing systems and thereby dramatically expanded their reach. And when technology is adopted by a much larger group, there is usually a corresponding explosion in applications of that technology as its users make their own discoveries about what the technology might be good for. The limitations of microcomputers relative to their more sophisticated predecessors – mainframes and minicomputers – also meant that existing, well-understood applications were yet to be successfully transferred from those more powerful and capable systems, leaving the door open for nimble, if somewhat less capable, alternatives to be brought to market.

The Capable User

All of these factors pointed towards a strategy where users of computers would not only need to be comfortable interacting with these systems, but where they would also need to have a broad range of skills and expertise, allowing them to go beyond simply using programs that other people had made. Instead, they would need to be empowered to modify existing programs and even write their own. With microcomputers only having a limited amount of memory and often less than convenient storage solutions (cassette tapes being a memorable example), and with few available programs for typically brand new machines, the emphasis of the manufacturer was often on giving the user the tools to write their own software.

Computer literacy efforts sensibly and necessarily went along with such trends, and from the late 1970s and early 1980s, after broader educational programmes seeking to inform the public about microelectronics and computing, these efforts targeted existing models of computer with learning materials like “30 Hour BASIC”. Traditional publishers became involved as the market opportunities grew for producing and selling such materials, and publications like Usbourne’s extensive range of computer programming titles were incredibly popular.

Numerous microcomputer manufacturers were founded, some rather more successful and long-lasting than others. An industry was born, around which was a vibrant community – or many vibrant communities – consuming software and hardware for their computers, but crucially also seeking to learn more about their machines and exchanging their knowledge, usually through the specialist print media of the day: magazines, newsletters, bulletins and books. This, then, was that golden age, of computer studies lessons at school, learning BASIC, and of late night coders at home, learning machine code (or, more likely, assembly language) and gradually putting together that game they always wanted to write.

One can certainly question the accuracy of the stereotypical depiction of that era, given that individual perspectives may vary considerably. My own experiences involved limited exposure to educational software at primary school, and the anticipated computer studies classes at secondary school never materialising. What is largely beyond dispute is that after the exciting early years of microcomputing, the educational curriculum changed focus from learning about computers to using them to run whichever applications happened to be popular or attractive to potential employers.

The Vocational Era

Thus, microcomputers became mere tools to do other work, and in that visionless era of Thatcherism, such other work was always likely to be clerical: writing letters and doing calculations in simple spreadsheets, sowing the seeds of dysfunction and setting public expectations of information systems correspondingly low. “Computer studies” became “information technology” in the curriculum, usually involving systems feigning a level of compatibility with the emerging IBM PC “standard”. Naturally, better-off schools will have had nicer equipment, perhaps for audio and video recording and digitising, plus the accompanying multimedia authoring tools, along with a somewhat more engaging curriculum.

At some point, the Internet will have reached schools, bringing e-mail and Web access (with all the complications that entails), and introducing another range of practical topics. Web authoring and Web site development may, if pursued to a significant extent, reveal such things as scripts and services, but one must then wonder what someone encountering the languages involved for the first time might be able to make of them. A generation or two may have grown up seeing computers doing things but with no real exposure to how the magic was done.

And then, there is the matter of how receptive someone who is largely unexposed to programming might be to more involved computing topics, lower-level languages, data structures and algorithms, of the workings of the machine itself. The mythology would have us believe that capable software developers needed the kind of broad exposure provided by the raw, unfiltered microcomputing experience of the 1980s to be truly comfortable and supremely effective at any level of a computing system, having sniffed out every last trick from their favourite microcomputer back in the day.

Those whose careers were built in those early years of microcomputing may now be seeing their retirement approaching, at least if they have not already made their millions and transitioned into some kind of role advising the next generation of similarly minded entrepreneurs. They may lament the scarcity of local companies in the technology sector, look at their formative years, and conclude that the system just doesn’t make them like they used to.

(Never mind that the system never made them like that in the first place: all those game-writing kids who may or may not have gone on to become capable, professional developers were clearly ignoring all the high-minded educational stuff that other people wanted them to study. Chess computers and robot mice immediately spring to mind.)

A Topic for Another Time

What we probably need to establish, then, is whether such views truly incorporate the wealth of experience present in society, or whether they merely reflect a narrow perspective where the obvious explanation may apply to some people’s experience but fails to explain the entire phenomenon. Here, we could examine teaching at a higher educational level than the compulsory school system, particularly because academic institutions were already performing and teaching computing for decades before controversies about the school computing curriculum arose.

We might contrast the casual, self-taught, experimental approach to learning about programming and computers with the structured approach favoured in universities, of starting out with high-level languages, logic, mathematics, and of learning about how the big systems achieved their goals. I encountered people during my studies who had clearly enjoyed their formative experiences with microcomputers becoming impatient with the course of these studies, presumably wondering what value it provided to them.

Some of them quit after maybe only a year, whereas others gained an ordinary degree as opposed to graduating with honours, but hopefully they all went on to lucrative and successful careers, unconstrained and uncurtailed by their choice. But I feel that I might have missed some useful insights and experiences had I done the same. But for now, let us go along with the idea that constructive exposure to technology throughout the formative education of the average person enhances their understanding of that technology, leading to a more sophisticated and creative population.

A Complete Experience

Backtracking to the article that started this article off, we then encounter one educational ambition that has seemingly remained unaddressed by the Raspberry Pi. In microcomputing’s golden age, the motivated learner was ostensibly confronted with the full power of the machine from the point of switching on. They could supposedly study the lowest levels and interact with them using their own software, comfortable with their newly acquired knowledge of how the hardware works.

Disregarding the weird firmware situation with the Pi, it may be said that most Pi users will not be in quite the same position when running the Linux-based distribution deployed on most units as someone back in the 1980s with their BBC Micro, one of the inspirations for the Pi. This is actually a consequence of how something even cheaper than a microcomputer of an earlier era has gained sophistication to such an extent that it is architecturally one of those “big systems” that stuffy university courses covered.

In one regard, the difference in nature between the microcomputers that supposedly conferred developer prowess on a previous generation and the computers that became widespread subsequently, including single-board computers like the Pi, undermines the convenient narrative that microcomputers gave the earlier generation their perfect start. Systems built on processors like the 6502 and the Z80 did not have different privilege levels or memory management capabilities, leaving their users blissfully unaware of such concepts, even if the curious will have investigated the possibilities of interrupt handling and been exposed to any related processor modes, or even if some kind of bank switching or simple memory paging had been used by some machines.

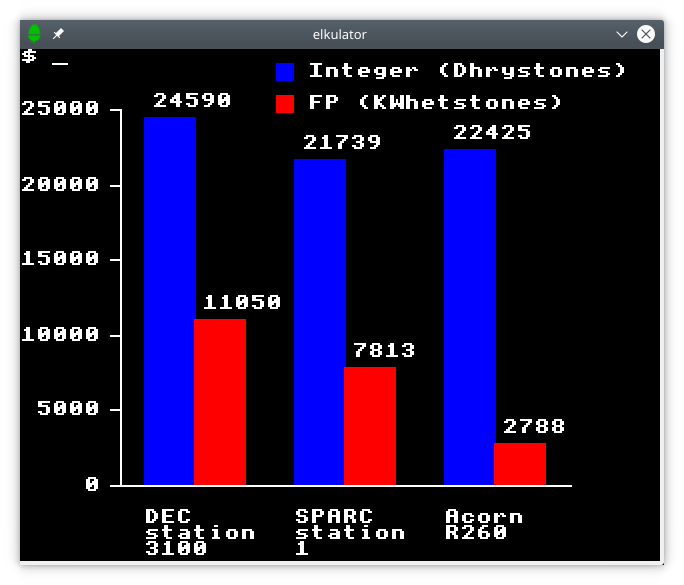

Indeed, topics relevant to microcomputers from the second half of the 1980s are surprisingly absent from retrocomputing initiatives promoting themselves as educational aids. While the Commander X16 is mostly aimed at those seeking a modern equivalent of their own microcomputer learning environment, and many of its users may also end up mostly playing games, the Agon Light and related products are more aggressively pitched as being educational in nature. And yet, these projects cling to 8-bit processors, some inviting categorisation as being more like microcontrollers than microprocessors, as if the constraints of those processor architectures conferred simplicity. In fact, moving up from the 6502 to the 68000 or ARM made life easier in many ways for the learner.

When pitching a retrocomputing product at an audience with the intention of educating them about computing, also adding some glamour and period accuracy to the exercise, it would arguably be better to start with something from the mid-1980s like the Atari ST, providing a more scalable processor architecture and sensible instruction set, but also coupling the processor with memory management hardware. The Atari ST and Commodore Amiga didn’t have a memory management unit in their earliest models, only introducing one later to attempt a move upmarket.

Certainly, primary school children might not need to learn the details of all of this power – just learning programming would be sufficient for them – but as they progress into the later stages of their education, it would be handy to give them new challenges and goals, to understand how a system works where each program has its own resources and cannot readily interfere with other programs. Indeed, something with a RISC processor and memory management capabilities would be just as credible.

How “authentic” a product with a RISC processor and “big machine” capabilities would be, in terms of nostalgia and following on from earlier generations of products, might depend on how strict one decides to be about the whole exercise. But there is nothing inauthentic about a product with such a feature set. In fact, one came along as the de-facto successor to the BBC Micro, and yet relatively little attention seems to be given to how it addressed some of the issues faced by the likes of the Pi.

Under The Hood

In assessing the extent of the Pi’s educational scope, the aforementioned article has this to say:

“Encouraging naive users to go under the hood is always going to be a bad idea on systems with other jobs to do.”

For most people, the Pi is indeed running many jobs and performing many tasks, just as any Linux system might do. And as with any “big machine”, the user is typically and deliberately forbidden from going “under the hood” and interfering with the normal functioning of the system. Even if a Pi is only hosting a single user, unlike the big systems of the past with their obligations to provide a service to many users.

Of course, for most purposes, such a system has traditionally been more than adequate for people to learn about programming. But traditionally, low-level systems programming and going under the hood generally meant downtime, which on expensive systems was largely discouraged, confined to inconvenient times of day, and potentially undertaken at one’s peril. Things have changed somewhat since the old days, however, and we will return to that shortly. But satisfying the expectations of those wanting a responsive but powerful learning environment was a challenge encountered even as the 1980s played out.

With early 1980s microcomputers like the BBC Micro, several traits comprised the desirable package that people now seek to reproduce. The immediacy of such systems allowed users to switch on and interact with the computer in only a few seconds, as opposed to a lengthy boot sequence that possibly also involved inserting disks, never mind the experiences of the batch computing era that earlier computing students encountered. Such interactivity lent such systems a degree of transparency, letting the user interact with the system and rapidly see the effects. Interactions were not necessarily constrained to certain facets of the system, allowing users to engage with the mechanisms “under the hood” with both positive and negative effects.

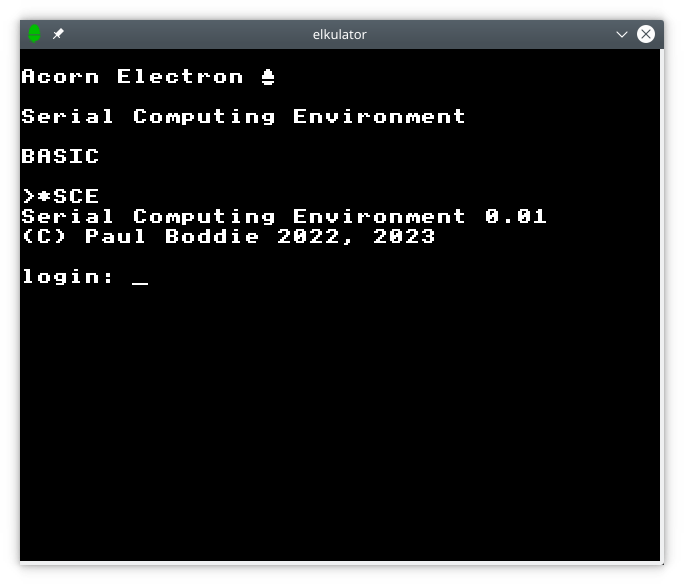

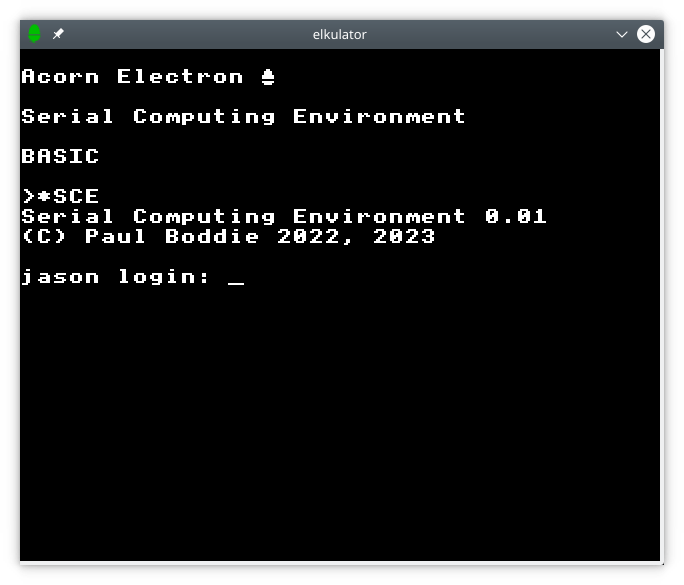

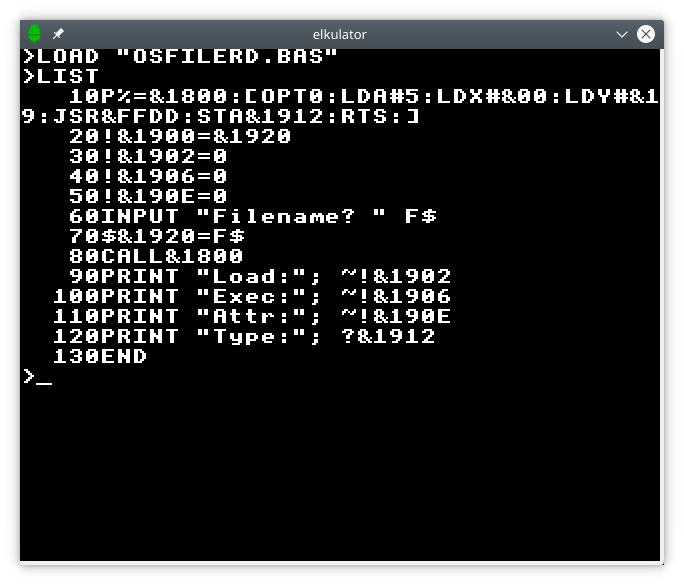

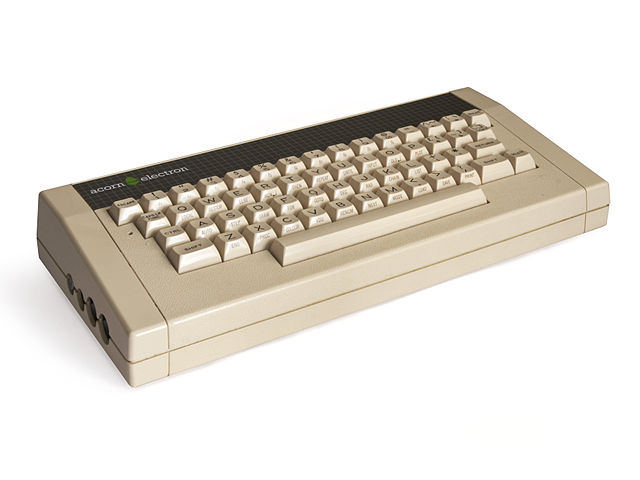

The Machine Operating System (MOS) of the BBC Micro and related machines such as the Acorn Electron and BBC Master series, provided well-defined interfaces to extend the operating system, introduce event or interrupt handlers, to deliver utilities in the form of commands, and to deliver languages and applications. Such capabilities allowed users to explore the provided functionality and the framework within which it operated. Users could also ignore the operating system’s facilities and more or less take full control of the machine, slipping out of one set of imposed constraints only to be bound by another, potentially more onerous set of constraints.

Earlier Experiences

Much is made of the educational impact of systems like the BBC Micro by those wishing to recapture some of the magic on more capable systems, but relatively few people seem to be curious about how such matters were tackled by the successor to the BBC Micro and BBC Master ranges: Acorn’s Archimedes series. As a step away from earlier machines, the Archimedes offers an insight into how simplicity and immediacy can still be accommodated on more powerful systems, through native support for familiar technology such as BASIC, compatibility layers for old applications, and system emulators for those who need to exercise some of the new hardware in precisely the way that worked on the older hardware.

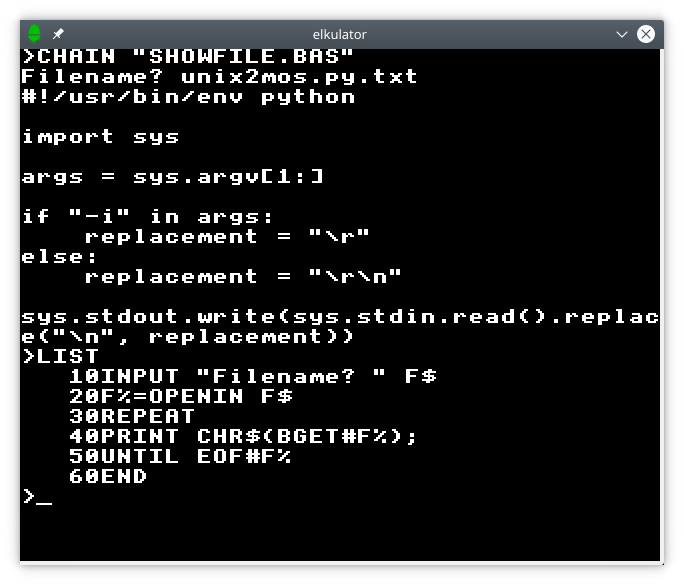

When the Archimedes was delivered, the original Arthur operating system largely provided the recognisable BBC Micro experience. Starting up showed a familiar welcome message, and even if it may have dropped the user at a “supervisor” prompt as opposed to BASIC, something which did also happen occasionally on earlier machines, typing “BASIC” got the user the rest of the way to the environment they had come to expect. This conferred the ability to write programs exercising the graphical and audio capabilities of the machine to a substantial degree, including access to assembly language, albeit of a different and rather superior kind to that of the earlier machines. Even writing directly to screen memory worked, albeit at a different location and with a more sensible layout.

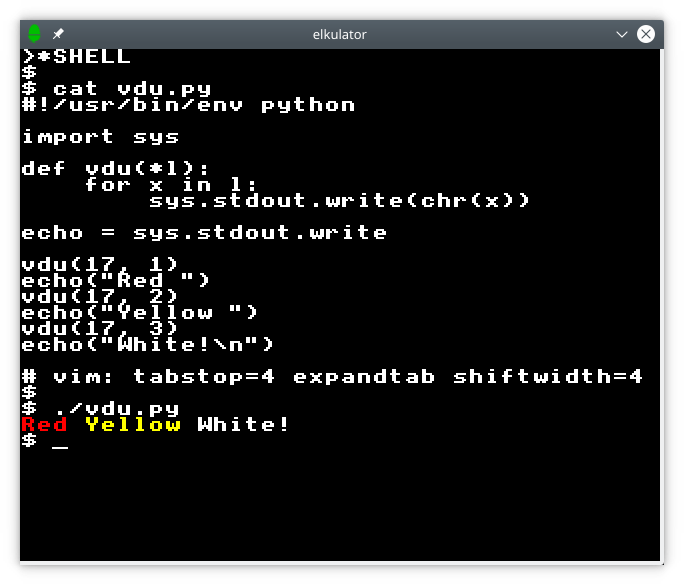

Under Arthur, users could write programs largely as before, with differences attributable to the change in capabilities provided by the new machines. Even though errant pokes to exotic memory locations might have been trapped and handled by the system’s enhanced architecture, it was still possible to write software that ran in a privileged mode, installed interrupt handlers, and produced clever results, at the risk of freezing or crashing the system. When Arthur was superseded by RISC OS, the desktop interface became the default experience, hiding the immediacy and the power of the command prompt and BASIC, but such facilities remained only a keypress away and could be configured as the default with perhaps only a single command.

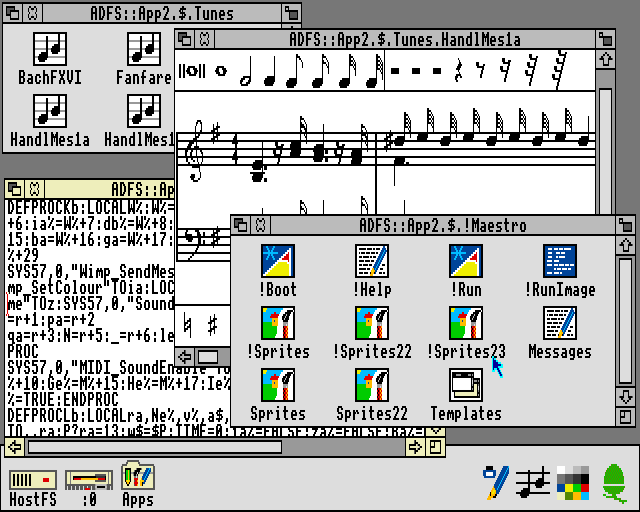

RISC OS exposed the tensions between the need for a more usable and generally accessible interface, potentially doing many things at once, and the desire to be able to get under the hood and poke around. It was possible to write desktop applications in BASIC, but this was not really done in a particularly interactive way, and programs needed to make system calls to interact with the rest of the desktop environment, even though the contents of windows were painted using the classic BASIC graphics primitives otherwise available to programs outside the desktop. Desktop programs were also expected to cooperate properly with each other, potentially hanging the system if not written correctly.

The Maestro music player in RISC OS, written in BASIC. Note that the !RunImage file is a BASIC program, with the somewhat compacted code shown in the text editor.

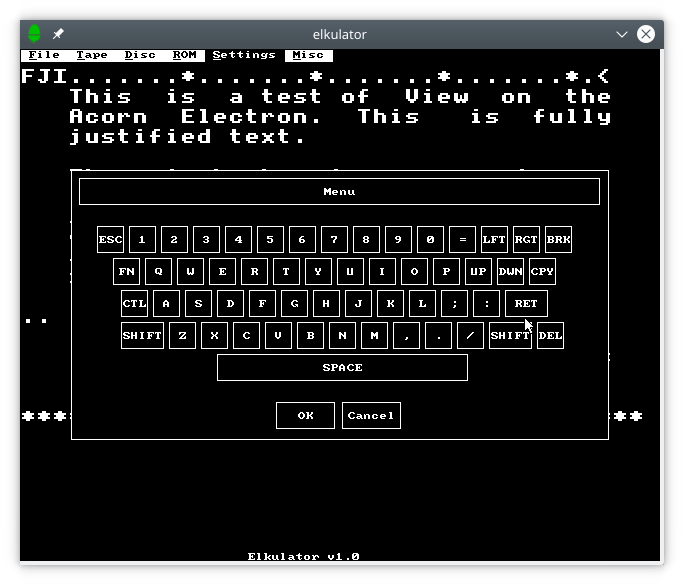

A safer option for those wanting the classic experience and to leverage their hard-earned knowledge, was to forget about the desktop and most of the newer capabilities of the Archimedes and to enter the BBC Micro emulator, 65Host, available on one of the supplied application disks, writing software just as before, and then running that software or any other legacy software of choice. Apart from providing file storage to the emulator and bearing all the work of the emulator itself, this did not really exercise the newer machine, but it still provided a largely authentic, traditional experience. One could presumably crash the emulated machine, but this should merely have terminated the emulator.

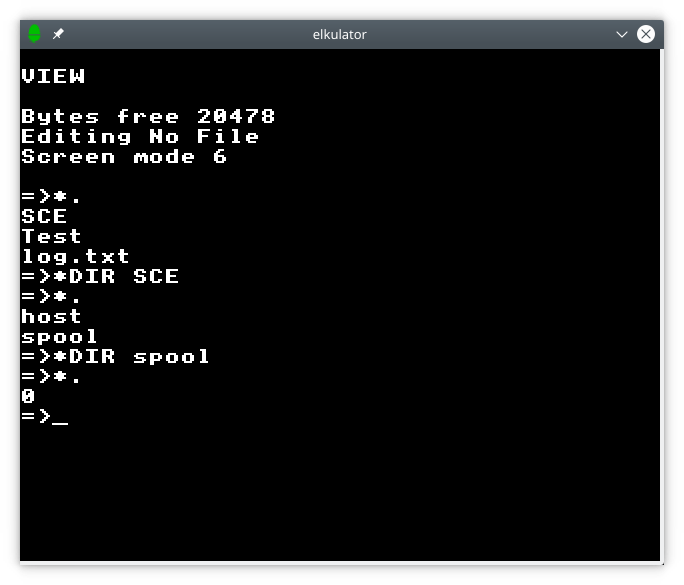

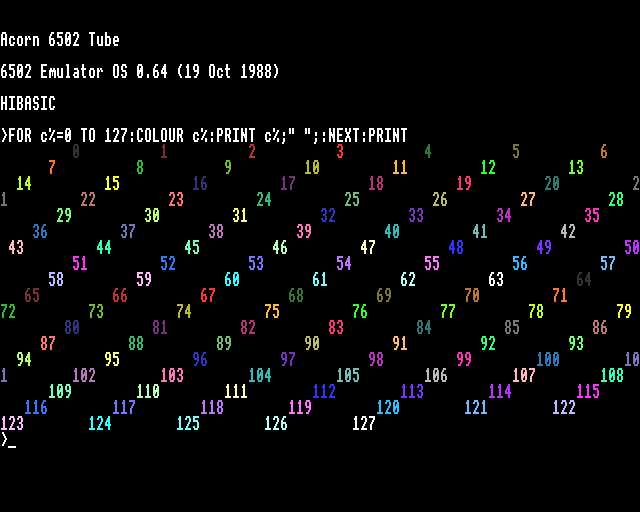

An intermediate form of legacy application support was also provided. 65Tube, with “Tube” referencing an interfacing paradigm used by the BBC Micro, allowed applications written against documented interfaces to run under emulation but accessing facilities in the native environment. This mostly accommodated things like programming language environments and productivity applications and might have seemed superfluous alongside the provision of a more comprehensive emulator, but it potentially allowed such applications to access capabilities that were not provided on earlier systems, such as display modes with greater resolutions and more colours, or more advanced filesystems of different kinds. Importantly, from an educational perspective, these emulators offered experiences that could be translated to the native environment.

65Tube running in MODE 15, utilising many more colours than normally available on earlier Acorn machines.

Although the Archimedes drifted away from the apparent simplicity of the BBC Micro and related machines, most users did not fully understand the software stack on such earlier systems, anyway. However, despite the apparent sophistication of the BBC Micro’s successors, various aspects of the software architecture were, in fact, preserved. Even the graphical user interface on the Archimedes was built upon many familiar concepts and abstractions. The difficulty for users moving up to the newer system arose upon finding that much of their programming expertise and effort had to be channelled into a software framework that confined the activities of their code, particularly in the desktop environment. One kind of framework for more advanced programs had merely been replaced by others.

Finding Lessons for Today

The way the Archimedes attempted to accommodate the expectations cultivated by earlier machines does not necessarily offer a convenient recipe to follow today. However, the solutions it offered should draw our attention to some other considerations. One is the level of safety in the environment being offered: it should be possible to interact with the system without bringing it down or causing havoc.

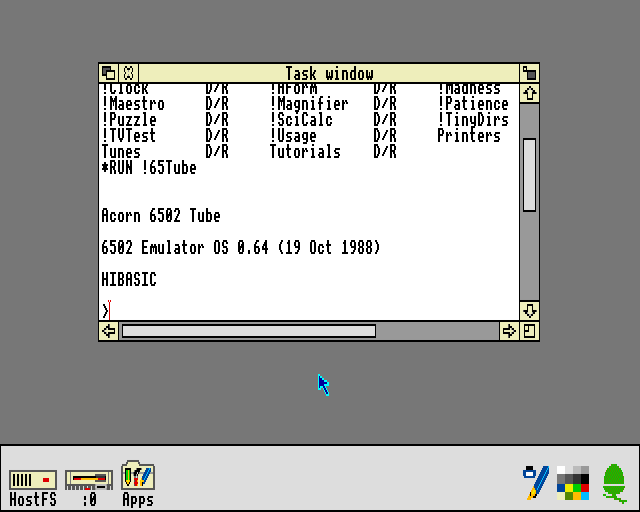

In that respect, the Archimedes provided a sandboxed environment like an emulator, but this was only really viable for running old software, as indeed was the intention. It also did not multitask, although other emulators eventually did. The more integrated 65Tube emulator also did not multitask, although later enhancements to RISC OS such as task windows did allow it to multitask to a degree.

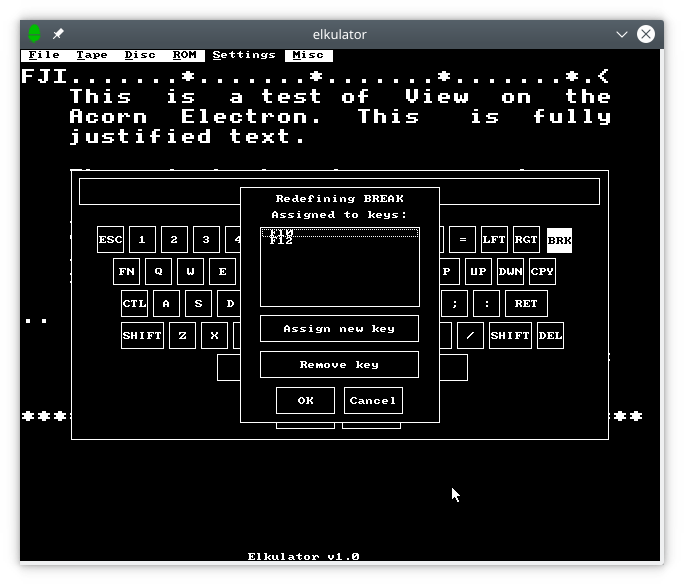

65Tube running in a task window. This relies on the text editing application and unfortunately does not support fancy output.

Otherwise, the native environment offered all the familiar tools and the desired level of power, but along with them plenty of risks for mayhem. Thus, a choice between safety and concurrency was forced upon the user. (Aside from Arthur and RISC OS, there was also Acorn’s own Unix port, RISC iX, which had similar characteristics to the kind of Linux-based operating system typically run on the Pi. You could, in principle, run a BBC Micro emulator under RISC iX, just as people run emulators on the Pi today.)

Today, we could actually settle for the same software stack on some Raspberry Pi models, with all its advantages and disadvantages, by running an updated version of RISC OS on such hardware. The bundled emulator support might be missing, however, but for those wanting to go under the hood and also take advantage of the hardware, it is unlikely that they would be so interested in replicating the original BBC Micro experience with perfect accuracy, instead merely seeking to replicate the same kind of experience.

Another consideration the Archimedes raises is the extent to which an environment may take advantage of the host system, and it is this consideration that potentially has the most to offer in formulating modern solutions. We may normally be completely happy running a programming tool in our familiar computing environments, where graphical output, for example, may be confined to a window or occasionally shown in full-screen mode. Indeed, something like a Raspberry Pi need not have any rigid notion of what its “native” graphical capabilities are, and the way a framebuffer is transferred to an actual display is normally not of any real interest.

The learning and practice of high-level programming can be adequately performed in such a modern environment, with the user safely confined by the operating system and mostly unable to bring the system down. However, it might not adequately expose the user to those low-level “under the hood” concepts that they seem to be missing out on. For example, we may wish to introduce the framebuffer transfer mechanism as some kind of educational exercise, letting the user appreciate how the text and graphics plotting facilities they use lead to pixels appearing on their screen. On the BBC Micro, this would have involved learning about how the MOS configures the 6845 display controller and the video ULA to produce a usable display.

The configuration of such a mechanism typically resides at a fairly low level in the software stack, out of the direct reach of the user, but allowing a user to reconfigure such a mechanism would risk introducing disruption to the normal functioning of the system. Therefore, a way is needed to either expose the mechanism safely or to simulate it. Here, technology’s steady progression does provide some possibilities that were either inconvenient or impossible on an early ARM system like the Archimedes, notably virtualisation support, allowing us to effectively run a simulation of the hardware efficiently on the hardware itself.

Thus, we might develop our own framebuffer driver and fire up a virtual machine running our operating system of choice, deploying the driver and assessing the consequences provided by a simulation of that aspect of the hardware. Of course, this would require support in the virtual environment for that emulated element of the hardware. Alternatively, we might allow some kind of restrictive access to that part of the hardware, risking the failure of the graphical interface if misconfiguration occurred, but hopefully providing some kind of fallback control mechanism, like a serial console or remote login, to restore that interface and allow the errant code to be refined.

A less low-level component that might invite experimentation could be a filesystem. The MOS in the BBC Micro and related machines provided filesystem (or filing system) support in the form of service ROMs, and in RISC OS on the Archimedes such support resides in the conceptually similar relocatable modules. Given the ability of normal users to load such modules, it was entirely possible for a skilled user to develop and deploy their own filesystem support, with the associated risks of bringing down the system. Linux does have arguably “glued-on” support for unprivileged filesystem deployment, but there might be other components in the system worthy of modification or replacement, and thus the virtual machine might need to come into play again to allow the desired degree of experimentation.

A Framework for Experimentation

One can, however, envisage a configurable software system where a user session might involve a number of components providing the features and services of interest, and where a session might be configured to exclude or include certain typical or useful components, to replace others, and to allow users to deploy their own components in a safe fashion. Alongside such activities, a normal system could be running, providing access to modern conveniences at a keypress or the touch of a button.

We might want the flexibility to offer something resembling 65Host, albeit without the emulation of an older system and its instruction set, for a highly constrained learning environment where many aspects of the system can be changed for better or worse. Or we might want something closer to 65Tube, again without the emulation, acting mostly as a “native” program but permitting experimentation on a few elements of the experience. An entire continuum of possibilities could be supported by a configurable framework, allowing users to progress from a comfortable environment with all of the expected modern conveniences, gradually seeing each element removed and then replaced with their own implementation, until arriving in an environment where they have the responsibility at almost every level of the system.

In principle, a modern system aiming to provide an “under the hood” experience merely needs to simulate that experience. As long as the user experiences the same general effects from their interactions, the environment providing the experience can still isolate a user session from the underlying system and avoid unfortunate consequences from that misbehaving session. Purists might claim that as long as any kind of simulation is involved, the user is not actually touching the hardware and is therefore not engaging in low-level development, even if the code they are writing would be exactly the code that would be deployed on the hardware.

Systems programming can always be done by just writing programs and deploying them on the hardware or in a virtual machine to see if they work, resetting the system and correcting any mistakes, which is probably how most programming of this kind is done even today. However, a suitably configurable system would allow a user to iteratively and progressively deploy a customised system, and to work towards deploying a complete system of their own. With the final pieces in place, the user really would be exercising the hardware directly, finally silencing the purists.

Naturally, given my interest in microkernel-based systems, the above concept would probably rest on the use of a microkernel, with much more of a blank canvas available to define the kind of system we might like, as opposed to more prescriptive systems with monolithic kernels and much more of the basic functionality squirrelled away in privileged kernel code. Perhaps the only difficult elements of a system to open up to user modification, those that cannot also be easily delegated or modelled by unprivileged components, would be those few elements confined to the microkernel and performing fundamental operations such as directly handling interrupts, switching execution contexts (threads), writing memory mappings to the appropriate registers, and handling system calls and interprocess communications.

Even so, many aspects of these low-level activities are exposed to user-level components in microkernel-based operating systems, leaving few mysteries remaining. For those advanced enough to progress to kernel development, traditional systems programming practices would surely be applicable. But long before that point, motivated learners will have had plenty of opportunities to get “under the hood” and to acquire a reasonable understanding of how their systems work.

A Conclusion of Sorts

As for why people are not widely using the Raspberry Pi to explore low-level computing, the challenge of facilitating such exploration when the system has “other jobs to do” certainly seems like a reasonable excuse, especially given the choice of operating system deployed on most Pi devices. One could remove those “other jobs” and run RISC OS, of course, putting the learner in an unfamiliar and more challenging environment, perhaps giving them another computer to use at the same time to look things up on the Internet. Or one could adopt a different software architecture, but that would involve an investment in software that few organisations can be bothered to make.

I don’t know whether the University of Cambridge has seen better-educated applicants in recent years as a result of Pi proliferation, or whether today’s applicants are as similarly perplexed by low-level concepts as those from the pre-Pi era. But then, there might be a lesson to be learned about applying some rigour to technological interventions in society. After all, there were some who justifiably questioned the effectiveness of rolling out microcomputers in schools, particularly when teachers have never really been supported in their work, as more and more is asked of them by their political overlords. Investment in people and their well-being is another thing that few organisations can be bothered to make, too.