Paul Boddie's Free Software-related blog

Paul's activities and perspectives around Free Software

Unix, the Minicomputer, and the Workstation

February 9th, 2026

Previously, I described the rise of Norsk Data in the minicomputer market and the challenges it faced, shared with other minicomputer manufacturers like Digital, but also mainframe companies like ICL and IBM, along with other technology companies like Xerox. Norsk Data may have got its commercial start in shipboard computers, understandable given Norway’s maritime heritage, but its growth was boosted by a lucrative contract with CERN to supply the company’s 16-bit minicomputers for use in accelerator control systems. Branching out into other industries and introducing 32-bit processors raised the company’s level of ambition, and soon enough Norsk Data’s management started seeing the company as a credible rival to Digital and other established companies.

Had the minicomputing paradigm remained ascendant, itself disrupting the mainframe paradigm, then all might have gone well, but just as Digital and others had to confront the emergence of personal computing, so did Norsk Data. Various traditional suppliers including Digital were perceived as tackling the threat from personal computers rather ineffectively, but they could not be accused of not having a personal computing strategy of their own. The strategists at Norsk Data largely stuck to their guns, however, insisting that minicomputers and terminals were the best approach to institutional computing.

Adamant that their NOTIS productivity suite and other applications were compelling enough reasons to invest in their systems, they tried to buy their way into new markets, ignoring the dynamics that were leading customers in other directions and towards other suppliers. Even otherwise satisfied customers were becoming impatient with the shortcomings of Norsk Data’s products and its refusal to engage substantially with emerging trends like graphical user interfaces, demonstrated by the Macintosh, a variety of products available for IBM-compatible personal computers, and the personal graphical workstation.

Worse is not Better

With Norsk Data’s products under scrutiny for their suitability for office applications, other deficiencies in their technologies were identified. The company’s proprietary SINTRAN III operating system still only offered a non-hierarchical filesystem as standard, with a conservative limit on the number of files each user could have. By late 1984, the Acorn Electron, my chosen microcomputer from the era, could support a hierarchical filesystem on floppy disks. And yet, here we have a “superminicomputer” belatedly expanding its file allowance in a simple, flat, user storage area from 256 files to an intoxicating 4096 on a comparatively huge and costly storage volume.

As one report noted, “a fundamental need with OA systems is for a hierarchical system”, which Norsk Data had chosen to provide via a separate NOTIS-DS (Data Storage) product, utilising a storage database that was generally opaque to the operating system’s own tools. A genuine hierarchical filesystem was apparently under development for SINTRAN IV, distinct from efforts to provide the hierarchical filesystem demanded by the company’s Unix implementation, NDIX.

SINTRAN’s advocates seem to have had the same quaint ideas about commands and command languages as advocates of other systems from the era, bemoaning “terse” Unix commands and its “powerful but obscure” shell. Some of them have evidently wanted to have it both ways, trotting out how the command to list files, being one that prompted the user in various ways, could be made to operate in a more concise and less interactive fashion if written in an abbreviated form. Commands and filenames could generally be abbreviated and still be located if the abbreviation could be unambiguously expanded to the original name concerned.

Of course, such “magic” was just a form of implicitly applying wildcard characters in the places where hyphens were present in an abbreviated name, and this could presumably have been problematic in certain situations. It comes across as a weak selling point indeed, at least if one is trying to highlight the powerful features of an operating system, rather than any given command shell. Especially when the humble Acorn Electron also supported things like abbreviated commands and abbreviated BASIC keywords, the latter often being a source of complaint by reviewers appalled at the effects on program readability.

For real-time purposes, SINTRAN III seemingly stacked up well against Digital’s RSX-11M, and offered a degree of consistency between Norsk Data’s 16- and 32-bit environments. Nevertheless, its largely satisfied users saw the benefits in what Unix could provide and hoped for an environment where SINTRAN and Unix could coexist on the same system, with the former supporting real-time applications.

Perhaps taking such remarks into account, Norsk Data commissioned Logica to port 4.2BSD to the ND-500 family. Due to the architecture of such systems, its Unix implementation, NDIX, would run on the ND-500 processor but lean on the ND-100 front-end processor running SINTRAN for peripheral input/output and other support, such as handling interrupts occurring on the ND-500 processor itself, introducing the notion of “shadow programs”, “shadow processes”, or “twin processes” running on the ND-100 to support the handling of page faults.

Burdening the 16-bit component of the system with the activity of its more powerful 32-bit companion processor seems to have led to some dissatisfaction with the performance of the resulting system. Claims of such problems, particularly in connection with NDIX, being resolved and delivering a better experience than a VAX-11/785 seem rather fragile given the generally poor adoption of NDIX and the company’s unwillingness to promote it. Indeed, in 1988, amidst turbulent times and the need to adapt to market realities, Unix at Norsk Data was something apparently confined to Intel-based systems running SCO Unix and merely labelled up to look like models in the ND-5000 range that had succeeded the ND-500.

Half-hearted adoption of Unix was hardly confined to Norsk Data. Unix had been developed on Digital hardware and that company had offered a variant for its PDP-11 systems, but it only belatedly brought its VAX-based product, Ultrix, to that system in 1984, seven years after the machine’s introduction. Even then, certain models in various ranges would not support Ultrix, or at least not initially. Mitigating this situation was the early and continuing availability of the Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) for the platform, this having been the basis for Ultrix itself.

Mainframe incumbents like IBM and ICL were also less than enthusiastic about Unix, at least as far as those mainframes were concerned. ICL developed a Unix environment for its mainframe operating system before going round again on the concept and eventually delivering its VME/X product to a market that, after earlier signals, perhaps needed to be convinced that the company was truly serious about Unix and open systems.

IBM had also come across as uncommitted to Unix, in contrast to its direct competitor in the mainframe market, Amdahl, whose implementation, UTS, had resulted from an early interest in efforts outside the company to port Unix to IBM-compatible mainframe hardware. IBM had contracted Interactive Systems Corporation to do a Unix port for the PC XT in the form of PC/IX, and as a response to UTS, ISC also did a port called IX/370 to IBM’s System/370 mainframes. Thereafter, IBM would partner with Locus Computing Corporation to make AIX PS/2 for its personal computers and, eventually in 1990, AIX/370 to update its mainframe implementation.

IBM’s Unix efforts coincided with its own attempts to enter the Unix workstation market, initially seeing limited success with the RT PC in 1985, and later seeing much greater success with the RS/6000 series in 1990. ICL seemed more inclined to steer customers favouring Unix towards its DRS “departmental” systems, some of which might have qualified as workstations. Both companies increasingly found themselves needing to convince such customers that Unix was not just an afterthought or a cynical opportunity to sell a few systems, but a genuine fixture in their strategies, provided across their entire ranges. Nevertheless, ICL maintained its DRS range and eventually delivered its DRS 6000 series, allegedly renamed from DRS 600 to match IBM’s model numbering, based on the SPARC architecture and System V Unix.

A lack of enthusiasm for Unix amongst minicomputer and mainframe vendors contrasted strongly with the aspirations of some microcomputer manufacturers. Acorn’s founder Chris Curry articulated such enthusiasm early in the 1980s, promising an expansion to augment the BBC Micro and possibly other models that would incorporate the National Semiconductor 32016 processor and run a Unix variant. Acorn’s approach to computer architecture in the BBC Micro was to provide an expandable core that would be relegated to handling more mundane tasks as the machine was upgraded to newer and better processors, somewhat like the way a microcontroller may be retained in various systems to handle input and output, interrupts and so on.

(Meanwhile, another microcomputer, the Dimension 68000, took the concept of combining different processors to an extreme, but unlike Acorn’s more modest approach of augmenting a 6502-based system with potentially more expensive processor cards, the Dimension offered a 68000 as its main processor to be augmented with optional processor cards for a 6502 variant, Z80 and 8086, these providing “emulation” capabilities for Apple, Kaypro and IBM PC systems respectively. Reviewers were impressed by the emulation support but unsure as to the demand for such a product in the market. Such hybrid systems seem to have always been somewhat challenging to sell.)

Acorn reportedly engaged Logica to port Xenix to the 32016, despite other Unix variants already existing, including Genix from National itself along with more regular BSD variants seen on the Whitechapel MG-1. Financial and technical difficulties appear to have curtailed Acorn’s plans, some of the latter involving the struggle for National to deliver working silicon, but another significant reason involves Acorn’s architectural approach, the pitfalls of which were explored and demonstrated by another company with connections to Acorn from the early 1980s, Torch Computers.

Tasked with covering the business angle of the BBC Micro, Torch delivered the first Z80 processor expansion for the system. The company then explored Acorn’s architectural approach by releasing second processor expansions that featured the Motorola 68000, intended to run a selection of operating systems including Unix. Although products were brought to market, and some reports even suggested that Torch had become one of the principal Unix suppliers in the UK in selling its Unicorn-branded expansions, it became evident that connecting a more powerful processor to an 8-bit system and relying on that 8-bit system to be responsible for input and output processing rather impeded the performance of the resulting system.

While servicing things like keyboards and printers were presumably within the capabilities of the “host” 8-bit system, storage needed higher bandwidth, particularly if hard drives were to be employed, and especially if increasingly desirable features such as demand paging were to be available in any Unix implementation. Torch realised that to remedy such issues, they would need to design a system from scratch, with the main processor and supporting chips having direct access to storage peripherals, leaving pretty much all of the 8-bit heritage behind. Their Triple-X workstation utilised the 68010 and offered a graphical Unix environment, elements of which would be licensed by NeXT for its own workstations.

Out of Acorn’s abandoned plans for a range of business machines, the company’s Cambridge Workstation, consisting of a BBC Micro with the 32016 expansion plus display, storage and keyboard, ran a proprietary operating system that largely offered the same kind of microcomputing paradigm as the BBC Micro, boosted by high-level language compilers and tools that were far more viable on the 32016 than the 6502. Nevertheless, Unix would remain unsupported, the memory management unit omitted from delivered forms of the Cambridge Workstation and related 32016 expansion. Eventually, Acorn would bring a more viable product to market in the form of its R-series workstations: entirely 32-bit machines based on the ARM architecture, albeit with their own shortcomings.

Norsk Data had also contracted out its Unix porting efforts to Logica, but unlike IBM, who had grasped the nettle with both hands to at least give the impression of taking Unix support seriously, Norsk Data took on the development of NDIX and seemingly proceeded with it begrudgingly, only belatedly supporting the models that were introduced. Even in captive markets where opportunities could be engineered, such as in the case of one initiative where Norsk Data systems were procured by the Norwegian state under a dubious scheme that effectively subsidised the company through sales of systems and services to regional computing centres, the models able to run NDIX were not necessarily the expensive flagship models that were sold in. With limited support for open systems and an emphasis on the increasingly archaic terminal-based model of providing computing services, that initiative was a costly failure.

Had NDIX been a compelling product, Norsk Data would have had a substantial incentive to promote it. From various documents, it seems that a certain amount of the NDIX development work was carried out at Norsk Data’s UK subsidiary, perhaps suffering in the midst of Wordplex-related intrigues towards the end of the 1980s. But at CERN, where demand might have been more easily generated, NDIX was regarded as “not being entirely satisfactory” after two years of effort trying to deliver it on the ND-500 series. The 16-bit ND-100 front-end processor was responsible for input and output, including to storage media, and the overheads imposed by this slower, more constrained system, undermined the performance of Unix on the ND-500.

Norsk Data, in conjunction with its partners and customers, had rediscovered what Torch had presumably identified in maybe 1984 or 1985 before that company swiftly pivoted to a new systems architecture to more properly enter the Unix workstation business at the start of 1986. One could argue that the ND-5000 series and later refinements, arriving from 1987 onwards, would change this situation somewhat for Norsk Data, but time and patience were perhaps running out even in the most receptive of environments to these newer developments.

The Spectre of the Workstation

The workstation looms large in the fate of Norsk Data, both as the instrument of its demise as well as a concept the company’s leadership never really seemed to fathom. Already in the late 1970s, the industry was being influenced by work done at Xerox on systems such as the Alto. Companies like Three Rivers Computer Corporation and Apollo Computer were being founded, and it was understandable that others, even in Norway, might be inspired and want a piece of the action.

To illustrate how the fate of many of these companies is intertwined, ICL had passed up on the opportunity of partnering with Apollo, choosing Three Rivers and adopting their PERQ workstation instead. At the time, towards the end of the 1970s, this seemed like the more prudent strategy, Three Rivers having the more mature product and being more willing to commit to Unix. But Apollo rapidly embraced the Motorola 68000 family, while the PERQ remained a discrete logic design throughout its commercial lifetime, eventually being described as providing “poor performance” as ICL switched to reselling Sun workstations instead.

Within Norsk Data, several engineers formulated a next-generation machine known as Nord-X, later deciding to leave the company and establish a new enterprise, Sim-X, to make computers with graphical displays based on bitslice technology, rather like machines such as the Alto and PERQ. One must wonder whether even at this early stage, a discussion was had about the workstation concept, only for the engineers to be told that this was not an area Norsk Data would prioritise.

Sim-X barely gets a mention in Steine’s account of the corporate history (“Fenomenet Norsk Data”, “The Norsk Data Phenomenon”), but it probably involves a treatment all by itself. The company apparently developed the S-2000 for graphical applications, initially for newspaper page layout, but also for other kinds of image processing. Later, it formed the basis of an attempt to make a Simula machine, in the same vein as the once-fashionable Lisp machine concept. Although Sim-X failed after a few years, one of its founders pursued the image processing system concept in the US with a company known as Lightspeed. Frustratingly minimal advertising for, and other coverage of, the Lightspeed Qolor can be found in appropriate industry publications of the era.

Since certain industry trends appear to have infiltrated the thinking at Norsk Data and motivated certain strategic decisions, it was not surprising that its early workstation efforts were focused on specific markets. It was not unusual for many computer companies in the early 1980s to become enthusiastic about computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM). Even microcomputer companies like Acorn and Commodore aspired to have their own CAD workstation, focused on electronic design automation (EDA) and preferably based on Unix, largely having to defer its realisation until a point in time when they had the technical capabilities to deliver something credible.

Norsk Data had identified a vehicle for such aspirations in the form of Dietz Computer Systems, producer of the Technovision CAD system for mechanical design automation. This acquisition seemed to work well for the combined company, allowing the CAD operation to take advantage of Norsk Data’s hardware and base complete CAD systems on it. Such special-purpose workstations were arguably justifiable in an era where particular display technologies were superior for certain applications and where computing resources needed to be focused on particular tasks. However, more versatile machines, again inspired by the Alto and PERQ, drove technological development and gradually eliminated the need to compromise in the utilisation of various technologies. For instance, screens could be high-resolution, multicolour and support vector and bitmap graphics at acceptable resolutions, even accelerating the vector graphics on a raster display to cater to traditional vector display applications.

In its key scientific and engineering markets, Norsk Data had to respond to industry trends and the activities of its competitors. Hewlett-Packard may have embraced Unix and introduced PA-RISC to its product ranges in 1986, largely to Norsk Data’s apparent disdain, but it had also introduced an AI workstation. Language system workstations had emerged in the early 1980s, initially emphasising Pascal as the PERQ had done. Lisp machines had for a time been all the rage, emphasising Lisp as a language for artificial intelligence, knowledge base development, and for application to numerous other buzzword technologies of the era, empowering individual users with interactive, graphical environments that were meant to confer substantial productivity benefits.

Thus, Norsk Data attempted to jump on the Lisp machine bandwagon with Racal, the company that would produce the telecoms giant Vodafone, hoping to leverage the ability to microcode the ND-500 series to produce a faster, more powerful system than the average Lisp machine vendor. Predictably, claims were made about this Knowledge Processing System being “10 to 20 times more powerful than a VAX” for the intended applications. Reportedly, the company delivered some systems, although Steine contradicts this, claiming that the only system that was sold – to the University of Oslo – was never delivered. This is not entirely true, either, judging from an account of a “a burned-up backplane” in the KPS-10 delivered to the Institute for Informatics. Intriguingly, hardware from one delivered system has since surfaced on the Internet.

One potentially insightful article describes the memory-mapped display capabilities of the KPS-10, supporting up to 36 bitmapped monochrome screens or bitplanes, with the hardware supposedly supporting communications with graphical terminals at distances of 100 metres, suggesting that, once again, the company’s dogged adherence to the terminal computing paradigm had overridden any customer demand for autonomous networked workstations. It had been noted alongside the ambitious performance claims that increased integration using gate arrays would make a “single-user work station” possible, but such refinements would only arrive later with the ND-5000 series. In the research community, Racal’s brief presence in the AI workstation market, aiming to support Lisp and Prolog on the ND-500 hardware, left users turning to existing products and, undoubtedly, conventional workstations once Racal and Norsk Data pulled out.

With Norsk Data having announced a broader collaboration with Matra in France, the two companies announced a planned “desktop minisupercomputer” emphasising vector processing, which is another area where competing vendors had introduced products in venues like CERN, threatening the adoption of Norsk Data’s products. Although the “minisupercomputer” aspect of such an effort might have positioned the product alongside other products in the category, the “desktop” label is a curious one coming from Norsk Data. Perhaps the company had been made aware of systems like the Silicon Graphics IRIS 4D and had hoped to capture some of the growing interest in such higher-performance workstations, redirecting that interest towards their own products and advocating for solutions similar to that of the KPS-10. In any case, nothing came of the effort, and so the company had nothing to show.

The intrusion of categories like “desktop” and “workstation” into Norsk Data’s marketing will have been the result of shifting procurement trends in venues like CERN. From being a core vendor to CERN, contracted to provide hardware under non-competitive arrangements, conditions in the organisation had started to change, and with efforts ramping up on the Large Electron-Positron collider (LEP), procurement directed towards workstations also started to ramp up. Initially, Apollo featured prominently, gaining from their “first mover” advantage, but they were later joined by Sun Microsystems. Even IBM’s PC RT had appealed to some in the organisation. And despite Digital being perceived as a minicomputer company, it was still managing to sell VAXstations into CERN.

One has to wonder what Norsk Data’s sales representatives in France must have made of it all. Hundreds of workstations from other companies being bought in, millions of Swiss francs being left on the table, and yet the models being brought to market for them to sell were based on the Butterfly workstation concept, featuring Technostation models for CAD and Teamstation models for NOTIS, neither of them likely to appeal to people looking beyond the personal computer and wanting workstation capabilities on their desk. A Butterfly workstation based on the 80286 running NOTIS on a 16-bit minicomputer expansion card must have seemed particularly absurd and feeble.

Increased integration brought the possibilities of smaller deskside systems from Norsk Data, with the ND-5800 and later models perhaps being more amenable to smaller workloads and workstation applications. But it seems that the mindset persisted of such systems being powerful minicomputers to be shared, rather than powerful workstations for individuals. Graphics cards embedding Motorola 68000 family processors augmented Technovision models targeting the CAD market, but as the end of the 1980s beckoned, such augmentations fell rather short of the kind of hardware companies like Sun and Silicon Graphics were offering. Meanwhile, only the company’s lower-end models could sell at around the kind of prices set by the mainstream workstation vendors, but with low-end performance to match.

In a retrospective of the company, chief executive Rolf Skår remarked that the workstation vendors had deliberately cut margins instead of charging what was considered to be the value of a computer for a particular customer, which is perhaps another way of describing a form of pricing where what the market will bear determines how high the price will be set, squeezing the customer as much as possible. The article, featuring an erroneous figure for the price of a typical Norsk Data computer (100,000 Norwegian crowns, being broadly equivalent to $10,000) misleads the reader into thinking that the company’s machines were not that expensive after all and even competitive on price with a typical Sun workstation.

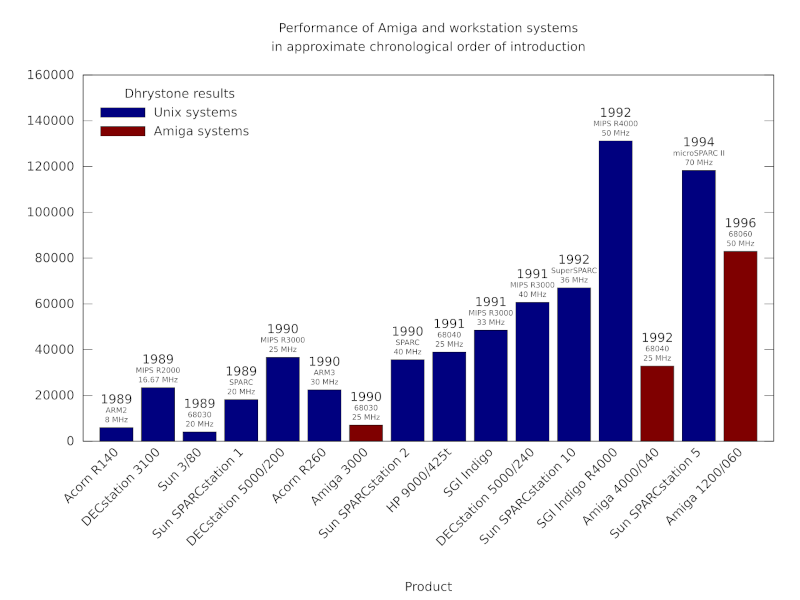

Evidently, there was confusion from Skår or the writer about the currencies involved, and such a computer would tend to cost more like 1 million crowns or $100,000: ten times that of the most affordable workstations. Norsk Data’s top-end machines ballooned in price in the mid-1980s, costing up to $500,000 for some single-processor models, and potentially $1.5 million for the very top-end four-processor configurations. Even with Sun introducing its first SPARC-based model at around $40,000, it could still outperform such “peak minicomputer” VAX and Norsk Data models and sell at a tenth of the price.

Norsk Data’s opportunistic pricing presumably tracked that of its big rival, Digital, and its own pricing of VAX models, sensing that if promoted as faster or better than the VAX, then potential customers would choose the Norsk Data machine, pricing and other characteristics being generally similar. When companies might have bought into a system with a big investment in information technology, this might have been a viable strategy, but as such technology became cheaper and available from numerous other providers, it became harder even for Digital to demand such a premium.

One can almost sense a sort of accusation that the workstation manufacturers ruined it for everyone, cheapening an otherwise lucrative market, but workstations were, of course, just another facet of the personal computing phenomenon and the gradual democratisation of computing itself. In the end, customers were always going to choose systems that delivered the computing power and user experience they desired, and it was simply a matter of those companies identifying and addressing such desires and needs, making such systems available at steadily more affordable prices, eventually coming to dominate the market. That Norsk Data’s management failed to appreciate such emerging trends, even when spelled out in black and white in procurement plans involving considerable sums of money, suggests that the blame for the company’s growth bonanza eventually coming to an end lay rather closer to home.

The Performance Game

With the ND-500 series, Norsk Data had been able to deliver floating-point performance that was largely competitive within the price bracket of its machines, and favourable comparisons were made between various ND-500 models and those in the VAX line-up, not entirely unjustifiably. Manufacturers who had not emphasised this kind of computation in their products found some kind of salvation in the form of floating-point processors or accelerators, made available by specialists like Mercury Computer Systems and Floating Point Systems, aided by the emergence of floating-point arithmetic chips from AMD and Weitek.

Presumably to fill a gap in its portfolio, Digital offered the Floating Point Systems accelerators in combination with some models. Meanwhile, the company had improved the performance of its VAX 8000 series to ostensibly eliminate many of Norsk Data’s performance claims. And curiously, Matra, who were supposed to be collaborating with Norsk Data on a vector computer, even offered the FPS products with the Norsk Data systems it had been selling, presumably to remedy a deficiency in its portfolio, but it is difficult to really know with a company like Matra.

Prior to the introduction of the ND-5000 series in 1987, Norsk Data had largely kept pace with their perceived competitors, alongside a range of other companies emphasising floating-point computation, but the company now needed to re-establish a lead over those competitors, particularly Digital. The ND-5000 series, employing CMOS gate array technology, was labelled as a “vaxkiller” in aggressive publicity but initially fell short of Norsk Data’s claims of better performance than the two-processor VAX 8800.

Using the only figures available to us, the top-end single-processor ND-5800 managed only 6.5 MWIPS and thus around 5 times the performance of the original VAX-11/780. In contrast, the dual-processor VAX 8800 was rated at around 9 times faster than its ancestor, with the single-processor VAX 8700 (later renamed to 8810) rated at around 6 times faster. All of these machines cost around half a million dollars. And yet, 1987 had seen some of the more potent first-generation RISC systems arrive in the marketplace from Hewlett-Packard and Silicon Graphics, both effectively betting their companies on the effectiveness of this technological phenomenon.

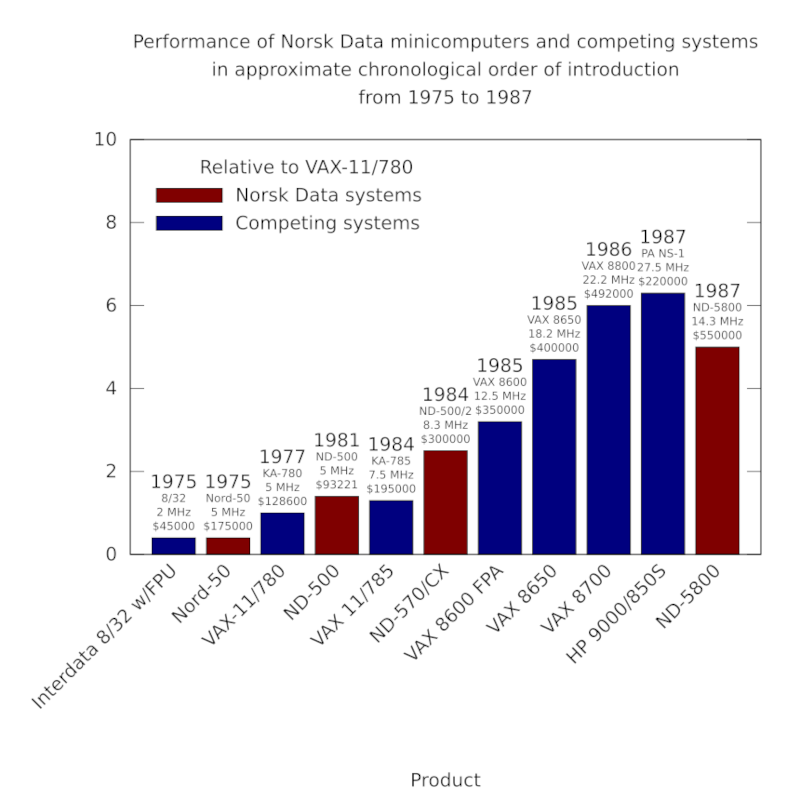

The performance of Norsk Data minicomputers and their competitors from 1975 to 1987. Although the ND-500 models were occasionally faster than the VAX machines at floating-point arithmetic, according to Whetstone benchmark results, Digital steadily improved its models, with the VAX 8700 of 1986 introducing similar architectural improvements to those introduced in the ND-5000 processors. Note how one of Hewlett-Packard’s first PA-RISC systems makes its mark alongside these established architectures.

Just as Digital’s management had kept RISC efforts firmly parked in the realm of “research”, even with completed RISC systems running Unix and feeding into more advanced research, Norsk Data’s technical leadership publicly dismissed RISC as a fad and their RISC competitors as unimpressive, even though the biggest names in computing – IBM, HP and Motorola – were at that very moment, formulating, developing and even delivering RISC products that threatened Norsk Data’s own products. RISC processors influenced and transformed the industry, and as the 1990s progressed, further performance gains were enabled by RISC architectural design principles.

To be fair to the designers at both Digital and Norsk Data, they also incorporated techniques often associated with RISC, just as Motorola had done while still downplaying the RISC phenomenon. The VAX 8800 and ND-5800 thus incorporated architectural improvements over their predecessors, such as pipelining, that provided at least a doubling of performance. The ND-5000 ES range, announced in 1988 and apparently available from 1989, were claimed to deliver another doubling in performance, seemingly through increasing the operating frequency. This, however, would merely put such server products alongside relatively low-cost RISC workstations using the somewhat established MIPS R2000 processor.

With Digital’s VAX 9000 project stalling, it was left to the CVAX, Rigel and NVAX processors to progressively follow through with the enhancements made in the VAX 8800, propagating them to more highly integrated processors and producing considerably faster and cheaper machines towards the end of the 1980s and into the early 1990s. But this consolidation, starting with the VAX 6000 series, and the accompanying modest gains in performance led to customer unease about the trailing performance of VAX systems, particularly amongst those customers interested in running Unix.

Thus, Digital introduced workstations and servers based on the MIPS architecture, delivering a performance boost almost immediately to those customers. A VAX 6000 processor could deliver around 7 times the performance of the original VAX-11/780, whereas a MIPS R2000-based DECstation 3100 could deliver around 11 times the performance. Crucially, such systems did not cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, but mere tens of thousands, with the lowest-end workstations costing barely ten thousand dollars.

To keep pace with these threats, it seems that Norsk Data’s final push involved a ramping up of the ND-5830 “Rallar” processor from an operating frequency of 25MHz to 45MHz in 1990 or so, just as the MIPS R3000 was proliferating in products from several vendors at more modest 25MHz and 33MHz frequencies but still nipping at the heels of this final, accelerated ND-5850 product. MIPS would suffer delays and limited availability of faster products like the R6000, also bringing consequences to the timely delivery of its 64-bit R4000 architecture. Nevertheless, products from IBM in its emerging RS/6000 range would arrive in the same year and demonstrate comprehensively superior performance to Norsk Data’s entire range.

Whetstone benchmark figures, particularly for the latter ND-5830 and ND-5850, are impressive. However, there may be caveats to claims of competitive performance. In one case, a ND-5800 system was reported as running a computational model in around 5 minutes with one set of parameters and 70 minutes with another. Meanwhile, the same inputs required respective running times of around 9 minutes and 78 minutes on a VAXstation 3500. The VAXstation 3500 was a 3 MWIPS system, whereas the ND-5800 was rated at around 6.5 MWIPS, and yet for a larger workload, it seems that any floating-point processing advantage of the ND-5800 was largely eliminated.

As for the integer or general performance of the ND-500 and ND-5000 families, Norsk Data appear to have been evasive. The company used “MIPS” to mean Whetstone MIPS, measuring floating-point performance, which was perhaps excusable for “number crunchers” but less applicable to other applications and a narrow measure that gave way to others over time, anyway. Otherwise, “relative performance” measures and numbers of users were often given, leaving us to wonder how the systems actually stacked up. LINPACK benchmark figures are few and far between, which is odd given the emphasis Norsk Data made on numerical computation when promoting the systems.

Another benchmark employed by Norsk Data concerned the company’s pivot to the “transaction processing” market with their high-end systems. Introducing the tpServer series based on its final ND-5000 range, the company stated a TP1 benchmark score of 10 transactions per second for its single-processor ND-5700 model, with a relative performance factor suggesting around 30 transactions per second for its single-processor ND-5850 model. Interestingly, its Uniline 88 range, introduced as the company also pivoted to more mainstream technology, was based on the Motorola 88000 architecture and also appears to have offered around 30 transactions per second, with similar scalability options involving up to four processors as with its tpServer and other traditional products.

The MC88100 used in the Uniline 88 showed similar general performance to competitors using the MIPS R3000 and SPARC processors, so we might conclude that the ND-5850 may have been comparable to and competitive with the mainstream at the turn of the 1990s. But this would mean that the ND-5000 series no longer offered any hope of differentiating itself from the mainstream in terms of performance. With Unix not being prioritised for the series, either, further development of the platform must have started to look like a futile and costly exercise, appealing to steadily fewer niche customers and gradually losing the revenue necessary for the substantial ongoing investment needed to keep it competitive. Switching to the 88000 family would give comparable performance, established and accepted Unix implementations, and broader industry support.

The ND-5850 arrived at a time when the MIPS R6000 and products from other industry players were experiencing difficulties in what might be considered a detour into emitter-coupled logic (ECL) fabrication, motivated by the purported benefits of the technology, somewhat replaying events from earlier times. Back in 1987, Norsk Data, had reportedly resisted the temptation to adopt ECL, sticking with the supposedly “ignored” (but actually ubiquitous) CMOS technology, and advertising this wisdom in the press. MIPS and Control Data Corporation would eventually bring the R6000 to market, but with far less success than hoped.

History would run full circle, however, and with the ND-5000 architecture having been consigned to maintenance status, and with Norsk Data having adopted the Motorola 88000 architecture for future high-end products, the engineering department of Norsk Data, spun-out into a separate company, would describe its plans of developing a superscalar variant of the 88000 to be fabricated in ECL and known as ORION. Perhaps not unsurprisingly, such plans met insurmountable but unspecified technical obstacles, and the product effectively evaporated, ending all further transformative aspirations in the processor business. Meanwhile, MIPS would, from 1992 onwards, at least have the consolation of delivering the 64-bit R4000 to market, aided by its CMOS fabrication partners.

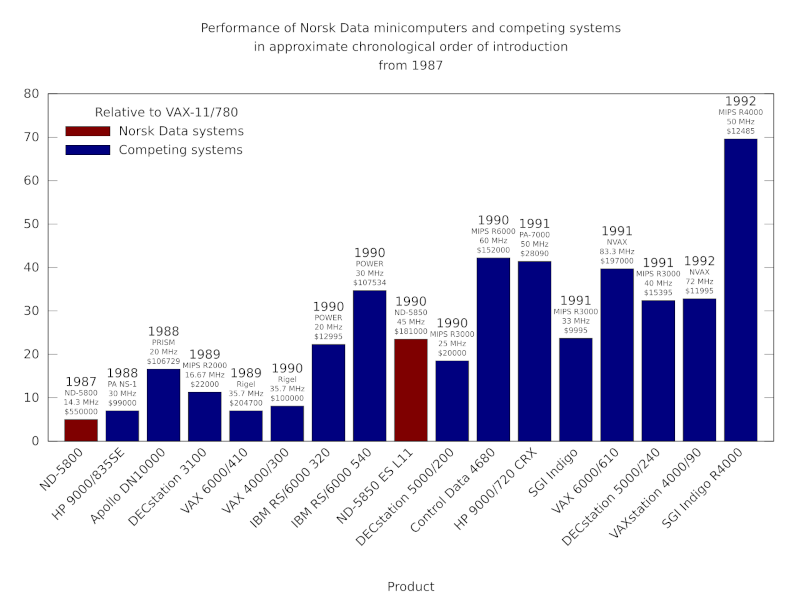

The performance of Norsk Data minicomputers and their competitors from 1987 onwards. The steady introduction of RISC products from Hewlett-Packard, Apollo Computer, Digital, IBM and others made the competitive landscape difficult for a low-volume manufacturer like Norsk Data. The company was soon having to contend with far cheaper workstation products from its competitors delivering comparable or superior performance (typically measured using SPECmark or SPECfp92 benchmarks here). Digital’s VAX products were also steadily improved and cost-reduced, but were eventually phased out in favour of Digital’s Alpha systems. In 1992, somewhat delayed, the MIPS R4000 appeared in systems like the SGI Indigo, offering a doubling of performance and maintaining the relentless pace of mainstream processor development.

Regardless, of whether specific Norsk Data products were better than specific products from its competitors, one is left wondering about that idea of Norsk Data making floating-point accelerators for other systems. After all, the ND-500 and ND-5000 processors were effectively accelerators for Norsk Data’s own 16-bit systems. And with that path having been taken, one might wonder whether the company would be the one having its offerings bundled by the likes of Digital. That a focus on such a market might have driven development at a faster tempo, pushing the company into the territory of floating-point specialists, minisupercomputers, and a lucrative market that would last until general-purpose products remedied their floating-point deficiencies, coupled with the rise of the RISC architectures.

Splitting off the floating-point expertise and coupling it with a variety of architectures in the form of a floating-point unit could have been an option. Indeed, Weitek, who had made such products the focus of their business apparently fabricated some of Norsk Data’s floating-point hardware for its later machines. Maybe there was good money in VLSI-fabricated Norsk Data accelerators for personal computers and workstations without great numeric processing options.

One might also wonder whether Norsk Data could have coupled its expertise in floating-point processing with an attractive instruction set architecture. Sadly, the company seemed wedded to the ND-500 architecture for compatibility reasons, involving an operating system that was not attractive to most potential customers, along with software that should have been portable and may not have been as desirable as perceived, anyway. Protecting the mirage of competitive advantage locked one form of expertise and potential commercial exploitation into others that were impeding commercial success.

The designers of the ND-5000 may have insisted that they could still match RISC designs even with their “complex instructions”, but Digital’s engineers had already concluded that their own comparable efforts to streamline VAX performance, achieving four- or five-fold gains within a couple of years, would remain inherently disadvantaged by the need to manage architectural complexity:

“So while VAX may “catch up” to current single-instruction-issue RISC performance, RISC designs will push on with earlier adoption of advanced implementation techniques, achieving still higher performance. The VAX architectural disadvantage might thus be viewed as a time lag of some number of years.”

In jettisoning the architectural baggage of the ND-500 architecture, Norsk Data’s intention was presumably to be able to more freely apply its expertise to the 88000 architecture, but all of this happened far too late in the day. To add insult to injury, it also involved the choice of what proved to be another doomed processor architecture.

Common Threads of Minicomputing History

January 9th, 2026

In the past few years, in my exploration of computing history, the case of the Norwegian computing manufacturer Norsk Data has been a particular fascination. Growing up in 1980s Britain, it is entirely possible that the name will have appeared in newspapers and magazines I may have seen or read, although I cannot remember any particular occurrences. It is also easy to mix it up with Nokia Data: a company that was eventually acquired by the United Kingdom’s own computing behemoth, ICL.

Looking back, however, and it turns out that Norsk Data even managed to get systems into institutions not too many miles from where I grew up, and the company did have a firm commercial presence in the UK, finding niches in various industries and forms of endeavour. Having now lived in Norway for a considerable amount of time, it is perhaps more surprising that Norsk Data is almost as forgotten, and leaves almost as few traces, in its home country.

When I arrived in Norway, I gave no thought whatsoever to Norsk Data, even though I had been working at an organisation that had been one of the company’s most prominent customers and the foundation for its explosive growth during the 1970s and 1980s. But my own path through the Norwegian computing sector may well have crossed those of the company’s many previous employees, and in fact, one former employer of mine was part of a larger group that had acquired parts of the disintegrating Norsk Data empire.

It might come as a surprise that a company with over 4000 employees at its peak, many of them presumably in Oslo, and with annual revenues of almost 3 billion Norwegian crowns (around $450 million), would crumble within years and leave so little behind to show for itself. Admittedly, some of the locations of the company’s facilities have been completely redeveloped in recent years. But one might have expected an enduring cultural or social legacy.

In looking back, we might make some observations about a phenomenon that shares certain elements with events in other countries and other companies, along with more general observations about technological aspiration, contrasting the aspirations of that earlier era with today’s “innovation” culture, where companies arguably have much more mundane goals.

Big Claims by Small People

One of my motivations for looking into the history of Norsk Data arose from studying some of the rhetoric about its achievements and its influences on mainstream technology and wider society, these intersecting with CERN and the World Wide Web. There are some that have dared to claim that the Web was practically invented on Norsk Data systems, and with that, imaginations run riot and other bold claims are made. I personally strongly dislike such behaviour.

When Apple devotees, for example, insist that Apple invented a range of technologies, the obligation is then put on others to correct the ignorant statements concerned and to act to prevent the historical record from being corrupted. So, no, Apple did not “invent” overlapping windows. And when corrected, one finds oneself obliged to chase down all the usual caveats and qualifications in response that are so often condensed into “but really they did”. So, no, Apple were not the first to demonstrate systems where the background windows remained “live” and updated, either.

Why can’t people be satisfied with the achievements that were made by their favourite companies? Is it not enough to respect the work actually done, instead of extrapolating and maximising a claim that then extends to a claim of “invention” and thus dominance? Such behaviour is not only disrespectful to the others who also did such work and made such discoveries, potentially at an earlier time, but it is disrespectful to the collaborative environment of the era, many of whose participants would not have seen themselves as adversaries. It is even disrespectful to the idols of the devotees making their exaggerated claims.

And if people revisited history, instead of being so intent on rewriting it, they might learn that such claims were litigated – literally – in decades past. Attempts to exclude other companies from delivering common technologies left Apple with little more than a trashcan. Maybe the company’s lawyers had wished that the perverse gesture of dragging a disk icon to a dustbin icon to eject a floppy disk might, for once, have just erased the company’s opportunistic, wasteful and flimsy lawsuit.

Questions of Heritage

What intrigued me most were some of the claims by Norsk Data itself. The company started out in the late 1960s, introducing the Nord-1, a 16-bit minicomputer, for industrial control applications. Numerous claims of “firsts” are made for that model in the context of minicomputing (virtual memory, built-in floating-point arithmetic support), perhaps contentious and subject to verification themselves, but it was the introduction of its successor where such claims start to tread on more delicate territory.

The Nord-5, introduced in 1972, has occasionally been claimed as the first 32-bit minicomputer. In fact, it could only operate in conjunction with a Nord-1, with the combination potentially being regarded as a minicomputing system. At the time, and for the handful of customers involved, this combination was described as the NORDIC system: a name that was apparently not used much if ever again. In practice, this was one or more 16-bit minicomputers with an attached 32-bit arithmetic processor.

Such clarifications might seem pedantic, but people do have strong opinions on such matters. Whereas Digital Equipment Corporation’s VAX, introduced in 1977, might be regarded as an influential machine in the proliferation of 32-bit minicomputing, occasionally and incorrectly cited as the first system of its kind, it is generally conceded that the Interdata 7/32 and 8/32, introduced in 1973, have a more substantial claim on any such title. Certainly, these may well have been the first minicomputers priced at $10,000 or below. Meanwhile, the NORDIC system cost over $600,000 for the Norwegian Meteorological Institute to acquire.

One might argue that NORDIC was not a typical minicomputing system, nor priced accordingly. And it does raise the observation that if one is to attach a component with certain superior characteristics to an existing component, as much as this attached component complements the capabilities of the existing component, the combination is not necessarily equivalent to a coherent system built entirely with such superior characteristics in the first place. We may return to this topic later, not least because certain phenomena have a habit of recurring in the computing industry.

As much as one might say in categorising the Nord-5, it was an interesting machine. Thanks to those who took an interest in archiving Norsk Data’s heritage, we are able to look at descriptions of the machine’s architecture, its instruction set, and so on. For those who have encountered systems from an earlier time and found them constraining and austere, the Nord-5 is surprising in a few ways. Most prominently, it has 64 general-purpose registers of 32 bits in size, pairs of which may be grouped to form 64-bit floating-point registers where required.

The Nord-5 has only a small number of instruction formats, although some of them seem rather haphazardly organised. It turns out that this is where the machine’s implementation, based heavily on discrete logic integrated circuits and the SN74181 arithmetic logic unit in particular, dictates the organisation of the machine. One might have thought that the limitations of the technology would have restrained the designers, making them focus on a limited feature set so as to minimise chip count and system cost, but exotic functionality exists that is difficult to satisfactorily explain or rationalise at first glance.

For instance, indirect addressing, familiar from various processor architectures, tends to involve an instruction accessing a particular memory location (or pair of locations), reading the contents of that location (or those locations), and then treating this value (or those values) as a memory address. Normally, one would then operate on the contents of this final address. However, in the Nord-5 architecture, such indirection can be done over and over again, so that instead of just one value being loaded and interpreted as an address, the value found at this address may be interpreted as an address, and its value may be interpreted as an address. And so on, for a maximum of sixteen levels, all traversed upon executing a single instruction over a number of clock cycles!

I must admit that I am not particularly familiar with mainframe and minicomputer architectures, but certain characteristics do seem similar to other machines. For example, the PDP-10 or DECsystem-10, a 36-bit mainframe from Digital introduced in 1966, has sixteen general-purpose registers and only two instruction formats. It also has floating-point arithmetic support using pairs of registers. Later, Digital would discontinue this line of computers in favour of its increasingly popular and profitable VAX range of computers: a development that would parallel Norsk Data’s own technological strategy in some ways.

The Nord-5 and its successor, the largely similar Nord-50, were regarded as commercially unsuccessful, although one might argue that the former gave the company access to funding at a crucial point in its history. They also delivered respectable floating-point arithmetic performance, bringing about considerations of making them available for minicomputers from other manufacturers. Described in some reporting as “a cheaper smaller scale version of the CDC Cyber 76 or Cray-1“, even if we ignore the hype, one can consider how pursuing this floating-point accelerator business might have influenced the eventual fate of the company.

Role Models and Rivals

In potentially lucrative sales environments like CERN, where Norsk Data gained a lucrative foothold during the 1970s, the company would have seen a lot of business going the way of companies like Digital, IBM and Hewlett-Packard. Such companies would have been almost like role models, indicating areas in which Norsk Data might operate, and providing recipes for winning business and keeping it.

Indeed, when discussing Norsk Data, it is almost impossible to avoid introducing Digital Equipment Corporation into the discussion, not least because Norsk Data constantly made comparisons of itself with Digital, favourably compared its products to those of Digital, and quite clearly aspired to be like Digital to the point of seemingly trying to emulate the more established company. However, it might be said that this approach rather depended on what Digital’s own strategy was perceived to be, and whether the people at Norsk Data actually understood Digital’s business and products.

Much has been written about Digital’s own fall from grace, being a company with sought-after products that helped define an industry, only to approach the end of the 1980s in a state of near crisis, with its products being outperformed by the insurgent Unix system vendors and with its own customers wanting a more convincing Unix story from their supplier. In certain respects, Norsk Data’s fortunes followed a similar path, and we might then be left wondering if in trying to be like Digital, the company inadvertently copied its larger rival’s flaws and replicated its mistakes.

One apparent perception of Digital was that of a complete provider of technology, and it is certainly apparent that Digital was the kind of supplier who would gladly provide everything from hardware and the operating system, through compilers, tools and productivity applications, all the way to removal services for computing facilities. Certainly, computing investments at the minicomputing and mainframe level were considerable, and having a capable vendor was essential.

It was apparently often remarked that “nobody ever got fired for buying IBM”, but it could also be said that buying IBM meant that a whole category of worries could be placed on the supplier. Indeed, Digital was perceived as only offering potential solutions through their technology, as opposed to the kind of complete, working solutions that IBM would be selling. Nevertheless, opportunities were identified in various areas where the bulk of such solutions were ready to deploy. Digital sought to enter the office automation market with its ALL-IN-1 software, competing with IBM’s established products. Naturally, Norsk Data wanted a piece of this action, too.

The business model was not the only way that Norsk Data seemed obsessed with Digital. Company financial reports highlighted the superior growth figures in comparison to Digital and other computer companies. The introduction of the VAX in 1977 demanded a response, and the company set to work on a genuine 32-bit “superminicomputer” as a result. This effort dragged out, however, only eventually delivering the ND-500 series in 1981.

The ND-500 introduced a new architecture incompatible with that of the Nord-5 and Nord-50, trading the large, general-purpose register set with a smaller set of registers partitioned into specialised groups acting as accumulators, index registers, extension registers, base registers, stack and frame registers, and so on. Although resembling an extended form of Norsk Data’s 16-bit architecture, no effort had been made to introduce instruction set compatibility between the ND-500 and that existing architecture.

The instruction set itself aimed for the orthogonality for which the VAX had become famous, implemented using microcode and supported by a variable-length instruction encoding. Instructions, consisting of instruction code and operand specifier units, could be a single byte or “several thousand bytes” in length. A variety of addressing modes and data types were supported in the large array of instructions and their variants.

And yet each ND-500 “processor” in any given configuration was still coupled with a 16-bit ND-100 “front-end”, this being an updated Nord-10 used for input/output and running much of the operating system, thus perpetuating the architectural relationship between the 16- and 32-bit components previously seen in the NORDIC system from several years earlier. In effect, the ND-500 still favoured computational workloads, and without the front-end unit, it could not be considered a minicomputing system in its own right.

Going Vertical

One distinct difference between the apparent strategy of Norsk Data and that of Digital, perhaps based on misconceptions of Digital’s approach or maybe founded on simple opportunism, was the way that the Norsk Data sought to be a complete, “vertically integrated” supplier in various specialised markets, whereas Digital could more accurately be described as a platform company. In one commentary I discovered while browsing, I found these pertinent remarks:

“In the old “Vertical” business model a major supplier would develop everything in house from basic silicon chips right through to … financial applications software packages. This model was clearly absurd. A company may be good at developing or providing several of the technologies and services in the value chain but it is inconceivable that any single company could be the best at doing everything.”

They originate from a representative of ICL, describing that company’s adoption of open standards and Unix as “a strategic platform”. Companies like ICL had their origins in earlier times when computer companies were almost expected to do everything for a customer, in part due to a lack of interoperability between systems, in part due to a traditional coupling of hardware and software, and in part due to a lack of expertise in information systems in the broader economy, making it a requirement for those companies to apply their proprietary technologies to the customer’s situation and to tackle each case as it came along.

Gradually, software became seen as an independent technology and product in its own right, interoperability materialised, and opportunities emerged for autonomous “third parties” in the industry. The “horizontal” model, where customers could choose and combine the technologies that were most appropriate for them, was resisted by various established companies, but in a dynamic market, they were eventually made to confront their own limitations.

In historical reviews of Norsk Data and its business, such as Tor Olav Steine’s “Fenomenet Norsk Data” (“The Norsk Data Phenomenon”), there is surprisingly little use of the word “solution” in the sense of an information technology system taken into practical use, which is a word that is used a lot in certain areas of the computer business. In those areas, like consultancy, the nature of the business may revolve entirely around the provision and augmentation of existing products to provide something a customer can use: what we call a “solution”. Such businesses simply could not exist without software and hardware platforms to deliver such solutions.

Where “solution” is used in such a way in Steine’s account, it is in the context of a company like Norsk Data choosing not to sell “solutions into specific markets” like the banking sector, identifying this a critical weakness of the company’s strategy. Certainly, a company like Norsk Data had to be adaptable and to accommodate initiatives to supply such sectors, but the mindset exhibited is that the company had to back up the salesforce with a “massive effort” to solve all of the customer’s problems. This was precisely the kind of “vertical” supplier that ICL and IBM had been out of historical necessity, entrusted with such endeavours, but also burdened by society’s continuing expectations of such companies.

Indeed, it says a great deal that IBM was the principal competition in the sector used to illustrate this alleged weakness of Norsk Data. IBM’s own crisis arrived in the early 1990s with a then-record financial loss and waves of reorganisations, somewhat decoupling the product divisions of the company from its growing services and solutions divisions, also gradually causing the company to adopt open systems and technologies. Its British counterpart in such traditional sectors, ICL, dabbled in open systems and Unix, largely keeping them away from its mainframe business, but pivoted strongly at the start of the 1990s, perhaps influenced by Fujitsu – its partner, investor and, eventually, owner – to adopt the SPARC architecture and System V Unix.

Norsk Data, however, stuck with vertical integration to its initial benefit and then its later detriment. The company had done some good business on the back of acquisitions in certain sectors – typesetting systems, computer-aided design/manufacturing – where opportunities were identified to migrate existing products to Norsk Data’s hardware and to ostensibly boost the performance that may have been lacking in the existing offerings, but the company found itself struggling to repeat such successes. In markets like the UK, it encountered indifference from software companies, who apparently perceived the company to be “too small”, and tried to invest in and cultivate smaller companies as vehicles for its technology.

Here, there may have been a possible lack of awareness or acceptance that instead of being “too small”, Norsk Data was perhaps too niche or too non-standard, in an era of emerging standards. After all, such standards increasingly defined software and hardware platforms on which other companies would build. The fixation on vertical market opportunities, having something that competitors did not, and “striking a knockout” in competitive situations, seems rather incompatible with cultivating an ecosystem around one’s products.

Another trait is apparent from discussion of the company, that being the tendency of selling in one set of products to a customer so as to be able to try and sell the customer another set of products. Thus, a customer buying one of the vertical market products might be coaxed into adopting various other strategic Norsk Data products, like the celebrated NOTIS suite of productivity applications. And with the potential for niche products to create opportunities for further sales and the proliferation of the company’s core technologies, Norsk Data got itself into trouble.

Personal Computing the Hard Way

Despite the increasing prominence of personal computing in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Norsk Data had remained largely dismissive of the trend, as many traditional vendors had also been initially. Minicomputer vendors sold multi-user machines that ran applications for each of the users, communicating output, usually character-based, to simple display terminals whose users would respond with keystrokes that would be communicated back to the “host”, thus providing an interactive computing environment. With shared storage, applications could provide a degree of collaboration absent from the average, standalone microcomputer. What exactly could a standalone microcomputer do that a terminal attached to a minicomputer could not?

Alongside this, applications that would become familiar to microcomputer users had emerged in minicomputer environments. For instance, word processing systems had demonstrated productivity benefits to organisations, providing far more flexibility and efficiency over typewriters and secretarial pools (also known as typing pools, so no, nothing to do with splashing around). Minicomputer environments could provide shared resources for still-expensive devices like printers, particularly high-end ones, and the shared storage permitted a library of materials to be accessed and curated.

From such easy triumphs in computerisation, much was anticipated from the nebulous practice of office automation. But perhaps because of the fragmented needs and demands of organisations, all-conquering big office systems could not hold off the gradual erosion of minicomputing dominance by the intrusion of microcomputers. Introduced at a relatable, personal level, one might argue that a personal computer as a simple product or commodity, along with software that was similarly packaged, may have been more obviously adaptable to some kinds of organisations, particularly small ones without strong expectations of what computer systems should do and how they might behave.

Indeed, where traditional suppliers of computers were perceived by newcomers as unapproachable or intimidating, microcomputers offered a potentially gentler introduction, as amusingly noted in one Norwegian article featuring IBM, Digital, HP and Norsk Data. For example, correspondence, documentation and other written records may have been cumbersome to prepare even with electronic typewriters – these providing only crude editing functions – and depending on the levels of enthusiasm for alternatives and frustration with the current situation, it would have been natural to acquire a personal computer with accessories, and to try out word processing and other applications to see what worked best for any given person, office, department, or organisation.

(A mixture of personal computing systems might have eventually generated interoperability problems, amongst others, but the agility that personal computers afforded organisations would potentially inform larger and more ambitious attempts to introduce technology later on.)

Personal computers began to shape user expectations of what computers of all kinds could do. Indeed, it is revealing that in treatments of the office automation market from the early 1980s, microcomputers keep recurring, and personal workstations – particularly the Xerox Star – set the tone for whatever office automation was meant to be. This was undoubtedly due to the unavoidable focus on the user interface that microcomputing and personal computing demanded. After all, personal computing cannot really be personal without considering the user!

Crucially, however, Xerox appeared to understand that one product could not be right for everyone, thus pitching a range of systems for a variety of users. The Xerox 860 focused largely on traditional word processing applications. The Xerox 8010 (or Star) was a networked workstation for sophisticated users. The company realised, particularly with IBM poised to move into personal computing, that a need existed for a more affordable product, leading to the much cheaper Xerox 820 running the established CP/M operating system. Although the Xerox 820 appears to have been considered a disappointment by commentators, who were perhaps expecting something more revolutionary, it did appear to signal that Xerox took affordable personal computing seriously, and the company was not alone in formulating such a product.

Digital tried a few different approaches to personal computing, two of which involved applications of their minicomputer architectures: the PDP-8-based DECmate, and the PDP-11-based DEC Professional. But it was their third and perhaps least proprietary approach, the DEC Rainbow, that perhaps stood the best chance of success, following a similar path to the Xerox 820, but taking the Zilog Z80-based core of such a machine and extending it with a companion Intel 8088 processor for increased versatility.

Such hybrid systems were not uncommon for a brief period at the start of the 1980s: established CP/M users would need Z80 compatibility, whereas new users and new software would have benefited from the 8088 running CP/M-86 or MS-DOS. The Rainbow was not a success, hampered by Digital’s proprietary instincts. Personally, I found it surprising to learn that the machine had a monochrome display as standard. Even with the RGB colour option, it would have rendered its own logo relatively unsatisfactorily!

What was Norsk Data’s response to the personal computing bandwagon? A telling quote can be found in an article from a 1985 newsletter:

“We do not believe in “the universal workstation” that can solve all problems for all user categories. Alternative hardware and software combinations seem to be the right answer. The functionality requirements for the personal workstations are definitely not satisfied by the “traditional PC”. For the majority of users today, the NOTIS terminal is the best alternative for a personal workstation that is integrated with the rest of the organization.”

The first two sentences seem reasonable enough, and the third could certainly have seemed reasonable at the time. But then comes the absurd, self-serving conclusion: a proprietary character terminal is the “best alternative” to something like the Xerox Star or its successor, the Xerox 6085 “Daybreak”, introduced in 1985, or other actual workstation products arriving on the market.

Evidently, decision-makers at the company remained fixated on what they considered their blockbuster products. But the personal computing trend was not about to disappear. The company’s first attempt at a product was initiated in 1983 and released in 1984, involving a rebadged IBM-PC-compatible from Columbia Computers, sold “half-heartedly” and was perhaps more influential within the company than outside.

Then, in 1986, came the product that only Norsk Data could make: the Butterfly workstation, featuring an Intel 80286 processor and running MS-DOS and contemporary Windows, but also featuring two expansion cards that implemented the ND-110 minicomputer processor to run the proprietary SINTRAN operating system. Naturally, such a workstation, with its built-in minicomputer, was intended to run the cherished NOTIS software, and a variant known as the Teamstation permitted the connection of four terminals to share in such goodness.

One can almost understand the thinking behind such products. There was an increasing clamour for approachable computing, with relatively low starting costs, and with buyers starting out with a single machine and seeing whether they liked the experience. Providing something whose experience for a single user could be expanded to cover another four users might have seemed like a reasonable idea. But to make sense to customers, those extra terminals would need to be inexpensive and offer something that another four personal computers might not, and the software involved would have to be better than the kinds of programs that ran natively on personal computers at the time. Here, the beliefs of those at Norsk Data and those of potential customers could easily have been rather different.

“Norsk Data didn’t buy Wordplex for nothing.” Norsk Data perhaps inadvertently played into 1980s stereotypes when boasting about having loads of money. Wordplex was a struggling word processing systems vendor, and the acquisition did not lead to the happy marriage of convenience – or otherwise – that was promised.

Turning Something into Nothing

Against the industry tide, it seems that the company did what came most naturally, seeking growth for its own applications amongst a captive customer audience. Thus, amidst a refinancing exercise at word processing supplier Wordplex, that turned into a takeover opportunity for Apricot Computers, Norsk Data barged in with a more valuable offer, leaving Apricot to withdraw from the contest, presumably with some relief. Wordplex, one of the success stories in an earlier phase of office automation, was struggling financially but had an enviable customer base in a market where Norsk Data had wanted a greater presence than it had previously managed to attain.

What the exact plan was for Wordplex is not entirely clear. The company had its own product roadmap, centred on its Zilog Z8000-based Series 8000 systems, initially running Wordplex’s proprietary operating system. Wordplex evidently acknowledged the emergence of Unix and sought to introduce Xenix for its systems, chosen perhaps for its continued support for the aging Z8000 architecture. Norsk Data’s contribution seems to have been to sell their own machines to “stand beside or stack vertically” on the Series 8000 machines, offering what looked suspiciously like the NOTIS suite. One could easily imagine that Wordplex’s product range was unlikely to receive much further development after that.

Commentators associated with Norsk Data seem to regard Wordplex as something of a misadventure. Steine goes as far as to accuse the Wordplex management of subverting the organisation and pursuing their own agenda, as opposed to getting on with their new duties of selling Norsk Data’s systems to those valuable customers. Yet he does seem to accept that by pushing new systems onto Wordplex’s customers, computing departments pushed back on the additional complexity these new, proprietary systems would introduce, although Steine seems to attribute such pushback more on an unwillingness to tolerate new vendors in their computer rooms.

Perhaps Wordplex’s management stuck to what they knew because they just weren’t given better tools for the job. Existing customers would want to see some continuity, even if their users would eventually see themselves migrated onto other technology. In the end, Norsk Data’s perceived opportunities never materialised, and Wordplex customers presumably saw the writing on the wall and migrated to other systems. The dedicated word processing business was being disrupted by low-cost personal computers either dressed up like word processors, in the case of the Amstrad PCW, or providing more general functionality, maybe even in a networked configuration.

It is telling that in the documentary covering the takeover, a remark is made about how Norsk Data seemed inexperienced at acquisitions and the task of integrating distinct corporate cultures, and yet the company had, in fact, acquired other companies to fuel its rapid growth. But still, it is apparent that entities like Comtec and Technovision remained distinct silos within the larger organisation. I have personal familiarity with one institutional customer of Comtec, although it may have been a faint memory by the time I interacted with its users.

That customer was CERN’s publishing section, responsible for the weekly Bulletin and other output, who had adopted the NORTEXT typesetting system with some success. In 1985, these users were gradually trying to adopt various NOTIS applications, expressing a form of cautious optimism. By 1986, with an audit of CERN’s information systems in progress, these users were facing an upgrade of NORTEXT that required terminals designed for NOTIS, as well as enhancements for NOTIS that stressed their older, 16-bit ND-100 series hardware, having been developed primarily for the newer, 32-bit, ND-500 systems.

More investment was requested to take advantage of newer hardware, increased storage, and to provide more terminals. Indeed, the introduction of ND-500 models would help to rationalise the hardware situation, reduce maintenance costs and demands, and provide better services to those users. But at the same time, amidst a “lively discussion”, the shortcomings of NOTIS were noted, that Norsk Data were “unlikely to satisfy the needs of the administration in terms of fully automated office functions such as agenda, calendars, conference scheduling”, and that better integration was needed with the growing Macintosh community inside CERN.

Indeed, the influence of the graphical user interface, and the success of the Macintosh in delivering a coherent platform for developers and users, put companies wedded to character-based terminal applications on the back foot. Graphical applications were the natural medium of such platforms, whereas companies like Norsk Data struggled to accommodate such applications within their paradigm, suggesting upgrades to more costly graphical terminals. At best, the result added around $1,000 to the cost of the terminal and merely offered an “experimental” and narrow attempt at being “Macintosh like”, in a world where potential users were more likely to opt for the real thing instead.

Despite the mythology around the Mac, the platform was, like many others, still finding its feet and lacking numerous desirable capabilities. The mid-1980s was a fluid era for the graphical personal computer, and although a similar mythology developed around the Amiga, which was more capable than the Mac in several respects, success for a platform demanded a combination of technology, applications, the convenience of making such applications, and a demand for them.

On the dominant IBM-compatible platform, it took a while for a dominant graphical layer to assert itself, leaving observers attempting to track the winner from candidates such as VisiOn, GEM, Windows, OS/2 and NewWave. It is perhaps unsurprising that Norsk Data had no ready answer, and that even as it introduced its own personal computers running DOS and early Windows software, it was merely waiting for an industry consensus to shake out. Other strategies could have been followed, however: vendors in Norsk Data’s situation chose to enter the workstation market, which is a topic to be considered in its own right.

Another company that struggled with personal computing was ICL. Having acquired some interesting products, such as those made by Singer Business Machines – a division of the Singer Corporation, perhaps most famous for its sewing machines – the same division, then operating as part as ICL, made a system that formed the basis of ICL’s Distributed Resource System product family. In the initial DRS 20 range, computers with 8085 processors running CP/M would run applications and access other machines acting as file servers over ICL’s proprietary Macrolan network.

Such solutions were not always well received by the personal computing media. Expectations that ICL would bring its market position to bear on the rapidly developing industry led to disappointment when the company introduced the first DRS models, drawing suggestions that the diskless “workstations” would make rather competitive personal computers, if only ICL were to remove the “nearly £1000” network card and replace it with a disk controller. Later models would upgrade the processor to the 8086 family and run Concurrent DOS. Low-end models did indeed get disk drives, but did not break out into the standalone personal computer market.

Instead, ICL also decided to sell a different set of products, licensed from a company called Rair, as its own Personal Computer series, and these even utilised similar technologies to its initial DRS line-up, such as the 8085, CP/M, and MP/M, but offered eight serial ports for connected terminals instead of network connectivity. Rair’s rise to prominence perhaps occurred through the introduction of the Rair Black Box, to which a terminal had to be attached in order to use the system. A repackaged version formed the basis of the first ICL PC.