Paul Boddie's Free Software-related blog

Paul's activities and perspectives around Free Software

Common Threads of Computer Company History

August 5th, 2025

When descending into the vaults of computing history, as I have found myself doing in recent years, and with the volume of historical material now available for online perusal, it has largely become possible to finally have the chance of re-evaluating some of the mythology cultivated by certain technological communities, some of it dating from around the time when such history was still being played out. History, it is said, is written by the winners, and this is true to a large extent. How often have we seen Apple being given the credit for many technological developments that were actually pioneered elsewhere?

But the losers, if they may be considered that, also have their own narratives about the failure of their own favourites. In “A Tall Tale of Denied Glory”, I explored some myths about Commodore’s Amiga Unix workstation and how it was claimed that this supposedly revolutionary product was destined for success, cheered on by the big names in workstation computing, only to be defeated by Commodore’s own management. The story turned out to be far more complicated than that, but it illustrates that in an earlier age where there was more limited awareness of an industry with broader horizons than many could contemplate, everyone could get round a simplistic tale and vent their frustration at the outcome.

Although different technological communities, typically aligned with certain manufacturers, did interact with each other in earlier eras, even if the interactions mostly focused on advocacy and argument about who had chosen the best system, there was always the chance of learning something from each other. However, few people probably had the opportunity to immerse themselves in the culture and folklore of many such communities at once. Today, we have the luxury of going back and learning about what we might have missed, reading people’s views, and even watching television programmes and videos made about the systems and platforms we just didn’t care for at the time.

It was actually while searching for something else, as most great discoveries seem to happen, that I encountered some more mentions of the Amiga Unix rumours, these being relatively unremarkable in their familiarity, although some of them were qualified by a claim by the person airing these rumours (for the nth time) that they had, in fact, worked for Sun. Of course, they could have been the mailboy for all I know, and my threshold for authority in potential source material for this matter is now set so high that it would probably have to be Scott McNealy for me to go along with these fanciful claims. However, a respondent claimed that a notorious video documenting the final days of Commodore covered the matter.

I will not link to this video for a number of reasons, the most trivial of which is that it just drags on for far too long. And, of course, one thing it does not substantially cover is the matter under discussion. A single screen of text just parrots the claims seen elsewhere about Sun planning to “OEM” the Amiga 3000UX without providing any additional context or verification. Maybe the most interesting thing for me was to see that Commodore were using Apollo workstations running the Mentor Graphics CAD suite, but then so were many other companies at one point in time or other.

In the video, we are confronted with the demise of a company, the accompanying desolation, cameraderie under adversity, and plenty of negative, angry, aggressive emotion coupled with regressive attitudes that cannot simply be explained away or excused, try as some commentators might. I found myself exploring yet another rabbit hole with a few amusing anecdotes and a glimpse into an era for which many people now have considerable nostalgia, but one that yielded few new insights.

Now, many of us may have been in similar workplace situations ourselves: hopeless, perhaps even deluded, management; a failing company shedding its workforce; the closure of the business altogether. Often, those involved may have sustained a belief in the merits of the enterprise and in its products and people, usually out of the necessity to keep going, whether or not the management might have bungled the company’s strategy and led it down a potentially irreversible path towards failure.

Such beliefs in the company may have been forged in earlier, more successful times, as a company grows and its products are favoured over those of the competition. A belief that one is offering something better than the competition can be highly motivating. Uncalibrated against the changing situation, however, it can lead to complacency and the experience of helplessly watching as the competition recover and recapture the market. Trapped in the moment, the sequence of events leading to such eventualities can be hard to unravel, and objectivity is usually left as a matter for future observers.

Thus, the belief often emerges that particular companies faced unique challenges, particularly by the adherents of those companies, simply because everything was so overwhelming and inexplicable when it all happened, like a perfect storm making an unexpected landfall. But, being aware of what various companies experienced, and in peeking over the fence or around the curtain at what yet another company may have experienced, it turns out that the stories of many of these companies all have some familiar, common themes. This should hardly surprise us: all of these companies will have operated largely within the same markets and faced common challenges in doing so.

A Tale of Two Companies

The successful microcomputer vendors of the 1980s, which were mostly those that actually survived the decade, all had to transition from one product generation to the next. Acorn, Apple and Commodore all managed to do so, moving up from 8-bit systems to more sophisticated systems using 32-bit architectures. But these transitions only got them so far, both in terms of hardware capabilities and the general sophistication of their systems, and by the early 1990s, another update to their technological platforms was due.

Acorn had created the ARM processor architecture, and this had mostly kept the company competitive in terms of hardware performance in its traditional markets. But it had chosen a compromised software platform, RISC OS, on which to base its Archimedes systems. It had also introduced a couple of Unix workstation products, themselves based on the Archimedes hardware, but these were trailing the pace in a much more competitive market. Acorn needed the newly independent ARM company to make faster, more capable chips, or it would need embrace other processor architectures. Without such a boost forthcoming, it dropped Unix and sought to expand in “longshot” markets like set-top boxes for video-on-demand and network computing.

Commodore had a somewhat easier time of it, at least as far as processors were concerned, riding on the back of what Motorola had to offer, which had been good enough during much of the 1980s. Like Acorn, Commodore made their own graphics chips and had enjoyed a degree of technical superiority over mainstream products as a result, but as Acorn had experienced, the industry had started to catch up, leading to a scramble to either deliver something better or to go with the mainstream. Unlike Acorn, Commodore did do a certain amount of business actually going with the mainstream and selling IBM-compatible PCs, although the increasing commoditisation of that business led the company to disengage and to focus on its own technologies.

Commodore had its own distractions, too. While Acorn pursued set-top boxes for high-bandwidth video-on-demand and interactive applications on metropolitan area networks, Commodore tried to leverage its own portfolio rather more directly, trading on its strengths in gaming and multimedia, hoping to be the one who might unite these things coherently and lucratively. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Japanese games console manufacturers had embraced the Compact Disc format, but NEC’s PC Engine CD-ROM² and Sega’s Mega-CD largely bolted CD technology onto existing consoles. Philips and Sony, particularly the former, had avoided direct competition with games consoles, pitching their CD-i technology more at the rather more sedate “edutainment” market.

With CDTV, Commodore attempted to enter the same market at Philips, downplaying the device’s Amiga 500 foundations and fast-tracking the product to market, only belatedly offering the missing CD-ROM drive option for its best-selling Amiga 500 system that would allow existing customers to largely recreate the same configuration themselves. Both CD-i and CDTV were considered failures, but Commodore wouldn’t let go, eventually following up with one of the company’s final products, the CD32, aiming more directly at the console market. Although a relative success against the lacklustre competition, it came too late to save the company which had entered a steep decline only to be driven to bankruptcy by a patent aggressor.

Whether plucky little Commodore would have made a comeback without financial headwinds and patent industry predators is another matter. Early multimedia consoles had unconvincing video playback capabilities without full-motion video hardware add-ons, but systems like the 3DO Interactive Multiplayer sought to strengthen the core graphical and gaming capabilities of such products, introducing hardware-accelerated 3D graphics and high-quality audio. Within only a year or so of the CD32’s launch, more complete systems such as the Sega Saturn and, crucially, the Sony PlayStation would be available. Commodore’s game may well have been over, anyway.

Back in Cambridge, a few months after Commodore’s demise, Acorn entered into a collaboration with an array of other local technology, infrastructure and media companies to deliver network services offering “interactive television“, video-on-demand, and many of the amenities (shopping, education, collaboration) we take for granted on the Internet today, including access to the Web of that era. Although Acorn’s core technologies were amenable to such applications, they did need strengthening in some respects: like multimedia consoles, video decoding hardware was a prerequisite for Acorn’s set-top boxes, and although Acorn had developed its own competent software-based video decoding technology, the market was coalescing around the MPEG standard. Fortunately for Acorn, MPEG decoder hardware was gradually becoming a commodity.

Despite this interactive services trial being somewhat informative about the application of the technologies involved, the video-on-demand boom fizzled out, perhaps demonstrating to Acorn once again that deploying fancy technologies in a relatively affluent region of the country for motivated, well-served early adopters generally does not translate into broader market adoption. Particularly if that adoption depended on entrenched utility providers having to break open their corporate wallets and spend millions, if not billions, on infrastructure investments that would not repay themselves for years or even decades. The experience forced Acorn to refocus its efforts on the emerging network computer trend, leading the company down another path leading mostly nowhere.

Such distractions arguably served both companies poorly, causing them to neglect their core product lines and to either ignore or to downplay the increasing uncompetitiveness of those products. Commodore’s efforts to go upmarket and enter the potentially lucrative Unix market had begun too late and proceeded too slowly, starting with efforts around Motorola 68020-based systems that could have opened a small window of opportunity at the low end of the market if done rather earlier. Unix on the 68000 family was a tried and tested affair, delivered by numerous companies, and supplied by established Unix porting houses. All Commodore needed to do was to bring its legendary differentiation to the table.

Indeed, Acorn’s one-time stablemate, Torch Computers, pioneered low-end graphical Unix computing around the earlier 68010 processor with its Triple X workstation, seeking to upgrade to the 68020 with its Quad X workstation, but it had been hampered by a general lack of financing and an owner increasingly unwilling to continue such financing. Coincidentally, at more or less the same time that the assets of Torch were finally being dispersed, their 68030-based workstation having been under development, Commodore demonstrated the 68030-based Amiga 3000 for its impending release. By the time its Unix variant arrived, Commodore was needing to bring far more to the table than what it could reasonably offer.

Acorn themselves also struggled in their own moves upmarket. While the ARM had arrived with a reputation of superior performance against machines costing far more, the march of progress had eroded that lead. The designers of the ARM had made a virtue of a processor being able to make efficient use of its memory bandwidth, as opposed to letting the memory sit around idle as the processor digested each instruction. This facilitated cheaper systems where, in line with the design of Acorn’s 8-bit computers, the processor would take on numerous roles within the system including that of performing data transfers on behalf of hardware peripherals, doing so quite effectively and obviating the need for costly interfacing circuitry that would let hardware peripherals directly access the memory themselves.

But for more powerful systems, the architectural constraints can be rather different. A processor that is supposedly inefficient in its dealings with memory may at least benefit from peripherals directly accessing memory independently, raising the general utilisation of the memory in the system. And even a processor that is highly effective at keeping itself busy and highly efficient at utilising the memory might be better off untroubled by interrupts from hardware devices needing it to do work for them. There is also the matter of how closely coupled the processor and memory should be. When 8-bit processors ran at around the same speed as their memory devices, it made sense to maximise the use of that memory, but as processors increased in speed and memory struggled to keep pace, it made sense to decouple the two.

Other RISC processors such as those from MIPS arrived on the market making deliberate use of faster memory caches to satisfy those processors’ efficient memory utilisation while acknowledging the increasing disparity between processor and memory speeds. When upgrading the ARM, Acorn had to introduce a cache in its ARM3 to try and keep pace, doing so with acclaim amongst its customers as they saw a huge jump in performance. But such a jump was long overdue, coming after Acorn’s first Unix workstation had shipped and been largely overlooked by the wider industry.

Acorn’s second generation of workstations, being two configurations of the same basic model, utilised the ARM3 but lacked a hardware floating-point unit. Commodore could rely on the good old 68881 from Motorola, but Acorn’s FPA10 (floating-point accelerator) arrived so late that only days after its announcement, three years or so after those ARM3-based systems had been launched and two years later than expected, Acorn discontinued its Unix workstation effort altogether.

It is claimed that Commodore might have skipped the 68030 and gone straight for the 68040 in its Unix workstation, but indications are that the 68040 was probably scarce and expensive at first, and soon only Apple would be left as a major volume customer for the product. All of the other big Motorola 68000 family customers had migrated to other architectures or were still planning to, and this was what Commodore themselves resolved to do, formulating an ambitious new chipset called Hombre based around Hewlett-Packard’s PA-RISC architecture that was never realised.

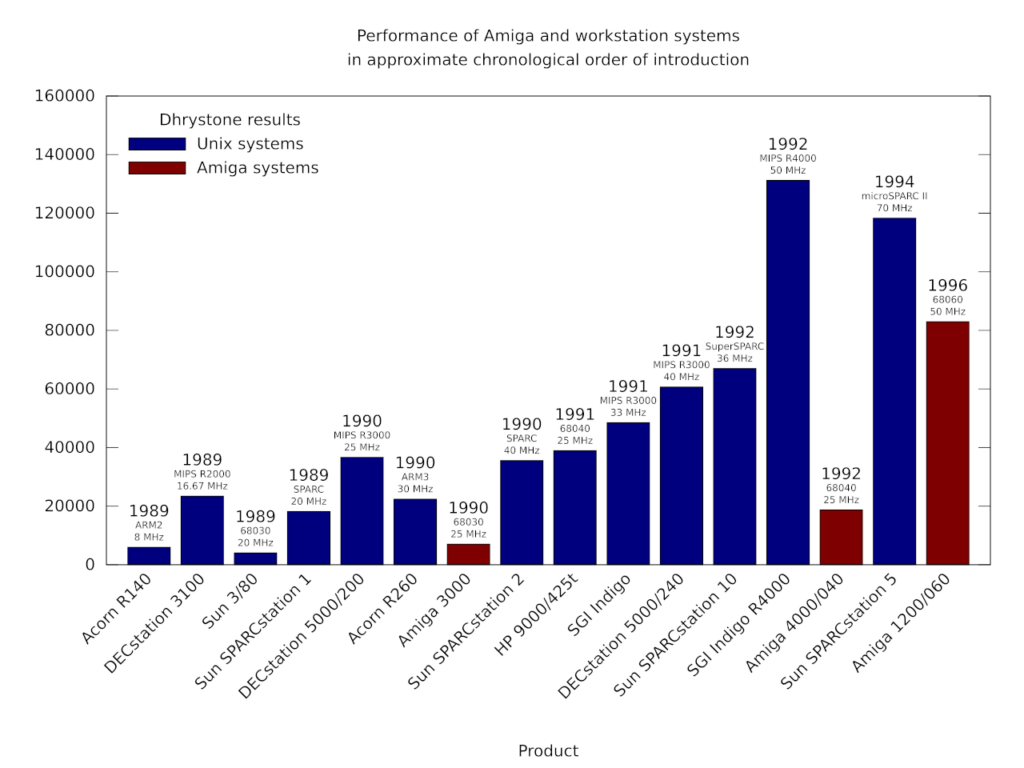

A chart showing how Unix workstation performance steadily improved, largely through the introduction of steadily faster RISC processors. Note how the HP 9000/425t gets quite impressive performance from the 68040. Even a system introduced with a 68060 straight off the first production run in 1994 would have been up against fearsome competition. Worth mentioning is that Acorn’s R140, although underpowered, was a low-cost colour workstation running Unix and the X Window System.

Acorn, meanwhile, finally got a chip upgrade from ARM in the form of the rather modest ARM6 series, choosing to develop new systems around the ARM600 and ARM610 variants, along with systems using upgraded sound and video hardware. One additional benefit of the newer ARM chips was an integrated memory management unit more suitable for Unix implementations than the one originally developed for the ARM. For followers of the company, such incoming enhancements provided a measure of hope that the company’s products would remain broadly competitive in hardware terms with mainstream personal computers.

Perhaps most important to most Acorn users at the time, given the modest gains they might see from the ARM600/610, was the prospect of better graphical capabilities, but Acorn chose not to release their intermediate designs along the way to their grand new system. And so, along came the Risc PC: a machine with two processor sockets and logic to allow one of the processors to be an x86-compatible processor that could run PC software. Once again, Acorn gave the whole hardware-based PC accelerator card concept another largely futile outing, failing to learn that while existing users may enjoy dabbling with software from another platform, it hardly ever attracts new customers in any serious numbers. Even Commodore had probably learned that lesson by then.

Nevertheless, Acorn’s Risc PC was a somewhat credible platform for Unix, if only Acorn hadn’t cancelled their own efforts in that realm. Prominent commentators and enthusiastic developers seized the moment, and with Free Software Unix implementations such as NetBSD and FreeBSD emerging from the shadow of litigation cast upon them, a community effort could be credibly pursued. Linux was also ported to ARM, but such work was actually begun on Acorn’s older A5000 model.

Acorn never seized this opportunity properly, however. Despite entering the network computer market in pursuit of some of Larry Ellison’s billions, expectations of the software in network computers had also increased. After all, networked computers have many of the responsibilities of those sophisticated minicomputers and workstations. But Acorn was still wedded to RISC OS and, for the most part, to ARM. And it ultimately proved that while RISC OS might present quite a nice graphical interface, it was actually NetBSD that could provide the necessary versatility and reliability being sought for such endeavours.

And as the 1990s got underway, the mundane personal computer started needing some of those workstation capabilities, too, eventually erasing the distinction between these two product categories. Tooling up for Unix might have seemed like a luxury, but it had been an exercise in technological necessity. Acorn’s RISC OS had its attractions, notably various user interface paradigms that really should have become more commonplace, together with a scalable vector font system that rendered anti-aliased characters on screen years before Apple or Microsoft managed to, one that permitted the accurate reproduction of those fonts on a dot-matrix printer, a laser printer, and everything in-between.

But the foundations of RISC OS were a legacy from Acorn’s 8-bit era, laid down hastily in an arguably cynical fashion to get the Archimedes out of the door and to postpone the consequences. Commodore inevitably had similar problems with its own legacy software technology, ostensibly more modern than Acorn’s when it was introduced in the Amiga, even having some heritage from another Cambridge endeavour. Acorn might have ported its differentiating technologies to Unix, following the path taken by Torch and its close relative, IXI, also using the opportunity to diversify its hardware options.

In all of this consideration given to Acorn and Commodore, it might seem that Apple, mentioned many paragraphs earlier, has been forgotten. In fact, Apple went through many of the same trials and ordeals as its smaller rivals. Indeed, having made so much money from the Macintosh, Apple’s own attempts to modernise itself and its products involve such a catalogue of projects and initiatives that even summarising them would expand this article considerably.

Only Apple would buy a supercomputer to attempt to devise its own processor architecture – Aquarius – only not to follow through and eventually be rescued by the pair of IBM and Motorola, humbled by an unanticipated decline in their financial and market circumstances. Or have several operating system projects – Opus, Pink, Star Trek, NuKernel, Copland – that were all started but never really finished. Or to get into personal digital assistants with the unfairly maligned Newton, or to consider redesigning the office entirely with its Workspace 2000 collaboration. And yet end up acquiring NeXT, revamping its technologies along that company’s lines, and still barely make it to the end of the decade.

The Final Chapters

Commodore got almost half-way through the 1990s before bankruptcy beckoned. Motorola’s 68060, informed by the work on the chip manufacturer’s abandoned 88000 RISC architecture, provided a considerable performance boost to its more established architecture, even if it now trailed the pack, perhaps only matching previous generations of SPARC and MIPS processors, and now played second fiddle to PowerPC in Motorola’s own line-up.

Acorn’s customers would be slightly luckier. Digital’s StrongARM almost entirely eclipsed ARM’s rather sedate ARM7-based offerings, except in floating-point performance in comparison to a single system-on-chip product, the ARM7500FE. This infusion of new technology was a blessing and a curse for Acorn and its devotees. The Risc PC could not make full use of this performance, and a new machine would be needed to truly make the most of it, also getting a long-overdue update in a range of core industry technologies.

Commodore’s devotees tend to make much of the company’s mismanagement. Deserved or otherwise, one may now be allowed to judge whether the company was truly unique in this regard. As Acorn’s network computer ambitions were curtailed, market conditions became more unfavourable to its increasingly marginalised platform, and the lack of investment in that core platform started to weigh heavily on the company and its customers. A shift in management resulted in a shift in business and yet another endeavour being initiated.

Acorn’s traditional business units were run down, the company’s next generation of personal computer hardware cancelled, and yet a somewhat tangential silicon design business was effectively being incubated elsewhere within the organisation. Meanwhile, Acorn, sitting on a substantial number of shares in ARM, supposedly presented a vulnerability for the latter and its corporate stability. So, a plan was hatched that saw Acorn sold off to a division of an investment bank based in a tax haven, the liberation of its shares in ARM, and the dispersal of Acorn’s assets at rather low prices. That, of course, included the newly incubated silicon design operation, bought by various figures in Acorn’s “senior management”.

Just as Commodore’s demise left customers and distributors seemingly abandoned, so did Acorn’s. While Commodore went through the indignity of rescues and relaunches, Acorn itself disappeared into the realms of anonymous holding companies, surfacing only occasionally in reports of product servicing agreements and other unglamorous matters. Acorn’s product lines were kept going for as long as could be feasible by distributors who had paid for the privilege, but without the decades of institutional experience of an organisation terminated almost overnight, there was never likely to be a glorious resurgence of its computer systems. Its software platform was developed further, primarily for set-top box applications, and survives today more as a curiosity than a contender.

In recent days, efforts have been made by Commodore devotees to secure the rights to trademarks associated with the company, these having apparently been licensed by various holding companies over the years. Various Acorn trademarks were also offloaded to licensors, leading to at least one opportunistic but ill-conceived and largely unwelcome attempt to trade on nostalgia and to cosplay the brand. Whether such attempts might occur in future remains uncertain: Acorn’s legacy intersects with that of the BBC, ARM and other institutions, and there is perhaps more sensitivity about how its trademarks might be used.

In all of this, I don’t want to downplay all of the reasons often given for these companies’ demise, Commodore’s in particular. In reading accounts of people who worked for the company, it is clear that it was not a well-run workplace, with exploitative and abusive behaviour featuring disturbingly regularly. Instead, I wish to highlight the lack of understanding in the communities around these companies and the attribution of success or failure to explanations that do not really hold up.

For instance, the Acorn Electron may have consumed many resources in its development and delivery, but it did not lead to Acorn’s “downfall”, as was claimed by one absurd comment I read recently. Acorn’s rescue by Olivetti was the consequence of several other things, too, including an ill-advised excursion into the US market, an attempt to move upmarket with an inadequate product range, some curious procurement and logistics practices, and a lack of capital from previous stock market flotations. And if there had been such a “downfall”, such people would not be piping up constantly about ARM being “the chip in everyone’s phone”, which is tiresomely fashionable these days. ARM may well have been just a short footnote in some dry text about processor architectures.

In these companies, some management decisions may have made sense, while others were clearly ill-considered. Similarly, those building the products could only do so much given the technological choices that had already been made. But more intriguing than the actual intrigues of business is to consider what these companies might have learned from each other, what the product developers might have borrowed from each other had they been able to, and what they might have achieved had they been able to collaborate somehow. Instead, both companies went into decline and ultimately fell, divided by the barriers of competition.

On a tale of two pull requests

June 15th, 2025

I was going to leave a comment on “A tale of two pull requests”, but would need to authenticate myself via one of the West Coast behemoths. So, for the benefit of readers of the FSFE Community Planet, here is my irritable comment in a more prominent form.

I don’t think I appreciate either the silent treatment or the aggression typically associated with various Free Software projects. Both communicate in some way that contributions are not really welcome: that the need for such contributions isn’t genuine, perhaps, or that the contributor somehow isn’t working hard enough or isn’t good enough to have their work integrated. Never mind that the contributor will, in many cases, be doing it in their own time and possibly even to fix something that was supposed to work in the first place.

All these projects complain about taking on the maintenance burden from contributions, yet they constantly churn up their own code and make work for themselves and any contributors still hanging on for the ride. There are projects that I used to care about that I just don’t care about any more. Primarily, for me, this would be Python: a technology I still use in my own conservative way, but where the drama and performance of Python’s own development can just shake itself out to its own disastrous conclusion as far as I am concerned. I am simply beyond caring.

Too bad that all the scurrying around trying to appeal to perceived market needs while ignoring actual needs, along with a stubborn determination to ignore instructive prior art in the various areas they are trying to improve, needlessly or otherwise, all fails to appreciate the frustrating experience for many of Python’s users today. Amongst other things, a parade of increasingly incoherent packaging tools just drives users away, heaping regret on those who chose the technology in the first place. Perhaps someone’s corporate benefactor should have invested in properly addressing these challenges, but that patronage was purely opportunism, as some are sadly now discovering.

Let the core developers of these technologies do end-user support and fix up their own software for a change. If it doesn’t happen, why should I care? It isn’t my role to sustain whatever lifestyle these people feel that they’re entitled to.

Consumerists Never Really Learn

May 15th, 2025

Via an article about a Free Software initiative hoping to capitalise on the discontinuation of Microsoft Windows 10, I saw that the consumerists at Which? had published their own advice. Predictably, it mostly emphasises workarounds that merely perpetuate the kind of bad choices Which? has promoted over the years along with yet more shopping opportunities.

Those workarounds involve either continuing to delegate control to the same company whose abandonment of its users is the very topic of the article, or to switch to another surveillance economy supplier who will inevitably do the same when they deem it convenient. Meanwhile, the shopping opportunities involve buying a new computer – as one would entirely expect from Which? – or upgrading your existing computer, but only “if you’re using a desktop”. I guess adding more memory to a laptop or switching to solid-state media, both things that have rejuvenated a laptop from over a decade ago that continues to happily runs Linux, is beyond comprehension at Which? headquarters.

Only eventually do they suggest Ubuntu, presumably because it is the only Linux distribution they have heard of. I personally suggest Debian. That laptop happily running Linux was running Ubuntu, since that is what it was shipped with, but then Ubuntu first broke upgrades in an unhelpful way, hawking commercial support in the update interface to the confusion of the laptop’s principal user (and, by extension, to my confusion as I attempted to troubleshoot this anomalous behaviour), and also managed to put out a minor release of Dippy Dragon, or whatever it was, that was broken and rendered the machine unbootable without appropriate boot media.

Despite this being a known issue, they left this broken image around for people to download and use instead of fixing their mess and issuing a further update. That this also happened during the lockdown years when I wasn’t able to personally go and fix the problem in person, and when the laptop was also needed for things like interacting with public health services, merely reinforced my already dim view of some of Ubuntu’s release practices. Fortunately, some Debian installation media rescued the situation, and a switch to Debian was the natural outcome. It isn’t as if Ubuntu actually has any real benefits over Debian any more, anyway. If anything, the dubious custodianship of Ubuntu has made Debian the more sensible choice.

As for Which? and their advice, had the organisation actually used its special powers to shake up the corrupt computing industry, instead of offering little more than consumerist hints and tips, all the while neglecting the fundamental issues of trust, control, information systems architecture, sustainability and the kind of fair competition that the organisation is supposed to promote, then their readers wouldn’t be facing down an October deadline to fix a computer that Which? probably recommended in the first place, loaded up with anti-virus nonsense and other workarounds for the ecosystem they have lazily promoted over the years.

And maybe the British technology sector would be more than just the odd “local computer repair shop” scratching a living at one end of the scale, a bunch of revenue collectors for the US technology industry pulling down fat public sector contracts and soaking up unlimited amounts of taxpayer money at the other, and relatively little to mention in between. But that would entail more than casual shopping advice and fist-shaking at the consequences of a consumerist culture that the organisation did little to moderate, at least while it could consider itself both watchdog and top dog.

Replaying the Microcomputing Revolution

January 6th, 2025

Since microcomputing and computing history are particular topics of interest of mine, I was naturally engaged by a recent article about the Raspberry Pi and its educational ambitions. Perhaps obscured by its subsequent success in numerous realms, the aspirations that originally drove the development of the Pi had their roots in the effects of the introduction of microcomputers in British homes and schools during the 1980s, a phenomenon that supposedly precipitated a golden age of hands-on learning, initiating numerous celebrated and otherwise successful careers in computing and technology.

Such mythology has the tendency to greaten expectations and deepen nostalgia, and when society enters a malaise in one area or another, it often leads to efforts to bring back the magic through new initiatives. Enter the Raspberry Pi! But, as always, we owe it to ourselves to step through the sequence of historical events, as opposed to simply accepting the narratives peddled by those with an agenda or those looking for comforting reminders of their own particular perspectives from an earlier time.

The Raspberry Pi and other products, such as the BBC Micro Bit, associated with relatively recent educational initiatives, were launched with the intention of restoring the focus of learning about computing to that of computing and computation itself. Once upon a time, computers were largely confined to large organisations and particular kinds of endeavour, generally interacting only indirectly with wider society. Thus, for most people, what computers were remained an abstract notion, often coupled with talk of the binary numeral system as the “language” of these mysterious and often uncompromising machines.

However, as microcomputers emerged both in the hobbyist realm – frequently emphasised in microcomputing history coverage – and in commercial environments such as shops and businesses, governments and educators identified a need for “computer literacy”. This entailed practical experience with computers and their applications, informed by suitable educational material, enabling the broader public to understand the limitations and the possibilities of these machines.

Although computers had already been in use for decades, microcomputing diminished the cost of accessible computing systems and thereby dramatically expanded their reach. And when technology is adopted by a much larger group, there is usually a corresponding explosion in applications of that technology as its users make their own discoveries about what the technology might be good for. The limitations of microcomputers relative to their more sophisticated predecessors – mainframes and minicomputers – also meant that existing, well-understood applications were yet to be successfully transferred from those more powerful and capable systems, leaving the door open for nimble, if somewhat less capable, alternatives to be brought to market.

The Capable User

All of these factors pointed towards a strategy where users of computers would not only need to be comfortable interacting with these systems, but where they would also need to have a broad range of skills and expertise, allowing them to go beyond simply using programs that other people had made. Instead, they would need to be empowered to modify existing programs and even write their own. With microcomputers only having a limited amount of memory and often less than convenient storage solutions (cassette tapes being a memorable example), and with few available programs for typically brand new machines, the emphasis of the manufacturer was often on giving the user the tools to write their own software.

Computer literacy efforts sensibly and necessarily went along with such trends, and from the late 1970s and early 1980s, after broader educational programmes seeking to inform the public about microelectronics and computing, these efforts targeted existing models of computer with learning materials like “30 Hour BASIC”. Traditional publishers became involved as the market opportunities grew for producing and selling such materials, and publications like Usbourne’s extensive range of computer programming titles were incredibly popular.

Numerous microcomputer manufacturers were founded, some rather more successful and long-lasting than others. An industry was born, around which was a vibrant community – or many vibrant communities – consuming software and hardware for their computers, but crucially also seeking to learn more about their machines and exchanging their knowledge, usually through the specialist print media of the day: magazines, newsletters, bulletins and books. This, then, was that golden age, of computer studies lessons at school, learning BASIC, and of late night coders at home, learning machine code (or, more likely, assembly language) and gradually putting together that game they always wanted to write.

One can certainly question the accuracy of the stereotypical depiction of that era, given that individual perspectives may vary considerably. My own experiences involved limited exposure to educational software at primary school, and the anticipated computer studies classes at secondary school never materialising. What is largely beyond dispute is that after the exciting early years of microcomputing, the educational curriculum changed focus from learning about computers to using them to run whichever applications happened to be popular or attractive to potential employers.

The Vocational Era

Thus, microcomputers became mere tools to do other work, and in that visionless era of Thatcherism, such other work was always likely to be clerical: writing letters and doing calculations in simple spreadsheets, sowing the seeds of dysfunction and setting public expectations of information systems correspondingly low. “Computer studies” became “information technology” in the curriculum, usually involving systems feigning a level of compatibility with the emerging IBM PC “standard”. Naturally, better-off schools will have had nicer equipment, perhaps for audio and video recording and digitising, plus the accompanying multimedia authoring tools, along with a somewhat more engaging curriculum.

At some point, the Internet will have reached schools, bringing e-mail and Web access (with all the complications that entails), and introducing another range of practical topics. Web authoring and Web site development may, if pursued to a significant extent, reveal such things as scripts and services, but one must then wonder what someone encountering the languages involved for the first time might be able to make of them. A generation or two may have grown up seeing computers doing things but with no real exposure to how the magic was done.

And then, there is the matter of how receptive someone who is largely unexposed to programming might be to more involved computing topics, lower-level languages, data structures and algorithms, of the workings of the machine itself. The mythology would have us believe that capable software developers needed the kind of broad exposure provided by the raw, unfiltered microcomputing experience of the 1980s to be truly comfortable and supremely effective at any level of a computing system, having sniffed out every last trick from their favourite microcomputer back in the day.

Those whose careers were built in those early years of microcomputing may now be seeing their retirement approaching, at least if they have not already made their millions and transitioned into some kind of role advising the next generation of similarly minded entrepreneurs. They may lament the scarcity of local companies in the technology sector, look at their formative years, and conclude that the system just doesn’t make them like they used to.

(Never mind that the system never made them like that in the first place: all those game-writing kids who may or may not have gone on to become capable, professional developers were clearly ignoring all the high-minded educational stuff that other people wanted them to study. Chess computers and robot mice immediately spring to mind.)

A Topic for Another Time

What we probably need to establish, then, is whether such views truly incorporate the wealth of experience present in society, or whether they merely reflect a narrow perspective where the obvious explanation may apply to some people’s experience but fails to explain the entire phenomenon. Here, we could examine teaching at a higher educational level than the compulsory school system, particularly because academic institutions were already performing and teaching computing for decades before controversies about the school computing curriculum arose.

We might contrast the casual, self-taught, experimental approach to learning about programming and computers with the structured approach favoured in universities, of starting out with high-level languages, logic, mathematics, and of learning about how the big systems achieved their goals. I encountered people during my studies who had clearly enjoyed their formative experiences with microcomputers becoming impatient with the course of these studies, presumably wondering what value it provided to them.

Some of them quit after maybe only a year, whereas others gained an ordinary degree as opposed to graduating with honours, but hopefully they all went on to lucrative and successful careers, unconstrained and uncurtailed by their choice. But I feel that I might have missed some useful insights and experiences had I done the same. But for now, let us go along with the idea that constructive exposure to technology throughout the formative education of the average person enhances their understanding of that technology, leading to a more sophisticated and creative population.

A Complete Experience

Backtracking to the article that started this article off, we then encounter one educational ambition that has seemingly remained unaddressed by the Raspberry Pi. In microcomputing’s golden age, the motivated learner was ostensibly confronted with the full power of the machine from the point of switching on. They could supposedly study the lowest levels and interact with them using their own software, comfortable with their newly acquired knowledge of how the hardware works.

Disregarding the weird firmware situation with the Pi, it may be said that most Pi users will not be in quite the same position when running the Linux-based distribution deployed on most units as someone back in the 1980s with their BBC Micro, one of the inspirations for the Pi. This is actually a consequence of how something even cheaper than a microcomputer of an earlier era has gained sophistication to such an extent that it is architecturally one of those “big systems” that stuffy university courses covered.

In one regard, the difference in nature between the microcomputers that supposedly conferred developer prowess on a previous generation and the computers that became widespread subsequently, including single-board computers like the Pi, undermines the convenient narrative that microcomputers gave the earlier generation their perfect start. Systems built on processors like the 6502 and the Z80 did not have different privilege levels or memory management capabilities, leaving their users blissfully unaware of such concepts, even if the curious will have investigated the possibilities of interrupt handling and been exposed to any related processor modes, or even if some kind of bank switching or simple memory paging had been used by some machines.

Indeed, topics relevant to microcomputers from the second half of the 1980s are surprisingly absent from retrocomputing initiatives promoting themselves as educational aids. While the Commander X16 is mostly aimed at those seeking a modern equivalent of their own microcomputer learning environment, and many of its users may also end up mostly playing games, the Agon Light and related products are more aggressively pitched as being educational in nature. And yet, these projects cling to 8-bit processors, some inviting categorisation as being more like microcontrollers than microprocessors, as if the constraints of those processor architectures conferred simplicity. In fact, moving up from the 6502 to the 68000 or ARM made life easier in many ways for the learner.

When pitching a retrocomputing product at an audience with the intention of educating them about computing, also adding some glamour and period accuracy to the exercise, it would arguably be better to start with something from the mid-1980s like the Atari ST, providing a more scalable processor architecture and sensible instruction set, but also coupling the processor with memory management hardware. The Atari ST and Commodore Amiga didn’t have a memory management unit in their earliest models, only introducing one later to attempt a move upmarket.

Certainly, primary school children might not need to learn the details of all of this power – just learning programming would be sufficient for them – but as they progress into the later stages of their education, it would be handy to give them new challenges and goals, to understand how a system works where each program has its own resources and cannot readily interfere with other programs. Indeed, something with a RISC processor and memory management capabilities would be just as credible.

How “authentic” a product with a RISC processor and “big machine” capabilities would be, in terms of nostalgia and following on from earlier generations of products, might depend on how strict one decides to be about the whole exercise. But there is nothing inauthentic about a product with such a feature set. In fact, one came along as the de-facto successor to the BBC Micro, and yet relatively little attention seems to be given to how it addressed some of the issues faced by the likes of the Pi.

Under The Hood

In assessing the extent of the Pi’s educational scope, the aforementioned article has this to say:

“Encouraging naive users to go under the hood is always going to be a bad idea on systems with other jobs to do.”

For most people, the Pi is indeed running many jobs and performing many tasks, just as any Linux system might do. And as with any “big machine”, the user is typically and deliberately forbidden from going “under the hood” and interfering with the normal functioning of the system. Even if a Pi is only hosting a single user, unlike the big systems of the past with their obligations to provide a service to many users.

Of course, for most purposes, such a system has traditionally been more than adequate for people to learn about programming. But traditionally, low-level systems programming and going under the hood generally meant downtime, which on expensive systems was largely discouraged, confined to inconvenient times of day, and potentially undertaken at one’s peril. Things have changed somewhat since the old days, however, and we will return to that shortly. But satisfying the expectations of those wanting a responsive but powerful learning environment was a challenge encountered even as the 1980s played out.

With early 1980s microcomputers like the BBC Micro, several traits comprised the desirable package that people now seek to reproduce. The immediacy of such systems allowed users to switch on and interact with the computer in only a few seconds, as opposed to a lengthy boot sequence that possibly also involved inserting disks, never mind the experiences of the batch computing era that earlier computing students encountered. Such interactivity lent such systems a degree of transparency, letting the user interact with the system and rapidly see the effects. Interactions were not necessarily constrained to certain facets of the system, allowing users to engage with the mechanisms “under the hood” with both positive and negative effects.

The Machine Operating System (MOS) of the BBC Micro and related machines such as the Acorn Electron and BBC Master series, provided well-defined interfaces to extend the operating system, introduce event or interrupt handlers, to deliver utilities in the form of commands, and to deliver languages and applications. Such capabilities allowed users to explore the provided functionality and the framework within which it operated. Users could also ignore the operating system’s facilities and more or less take full control of the machine, slipping out of one set of imposed constraints only to be bound by another, potentially more onerous set of constraints.

Earlier Experiences

Much is made of the educational impact of systems like the BBC Micro by those wishing to recapture some of the magic on more capable systems, but relatively few people seem to be curious about how such matters were tackled by the successor to the BBC Micro and BBC Master ranges: Acorn’s Archimedes series. As a step away from earlier machines, the Archimedes offers an insight into how simplicity and immediacy can still be accommodated on more powerful systems, through native support for familiar technology such as BASIC, compatibility layers for old applications, and system emulators for those who need to exercise some of the new hardware in precisely the way that worked on the older hardware.

When the Archimedes was delivered, the original Arthur operating system largely provided the recognisable BBC Micro experience. Starting up showed a familiar welcome message, and even if it may have dropped the user at a “supervisor” prompt as opposed to BASIC, something which did also happen occasionally on earlier machines, typing “BASIC” got the user the rest of the way to the environment they had come to expect. This conferred the ability to write programs exercising the graphical and audio capabilities of the machine to a substantial degree, including access to assembly language, albeit of a different and rather superior kind to that of the earlier machines. Even writing directly to screen memory worked, albeit at a different location and with a more sensible layout.

Under Arthur, users could write programs largely as before, with differences attributable to the change in capabilities provided by the new machines. Even though errant pokes to exotic memory locations might have been trapped and handled by the system’s enhanced architecture, it was still possible to write software that ran in a privileged mode, installed interrupt handlers, and produced clever results, at the risk of freezing or crashing the system. When Arthur was superseded by RISC OS, the desktop interface became the default experience, hiding the immediacy and the power of the command prompt and BASIC, but such facilities remained only a keypress away and could be configured as the default with perhaps only a single command.

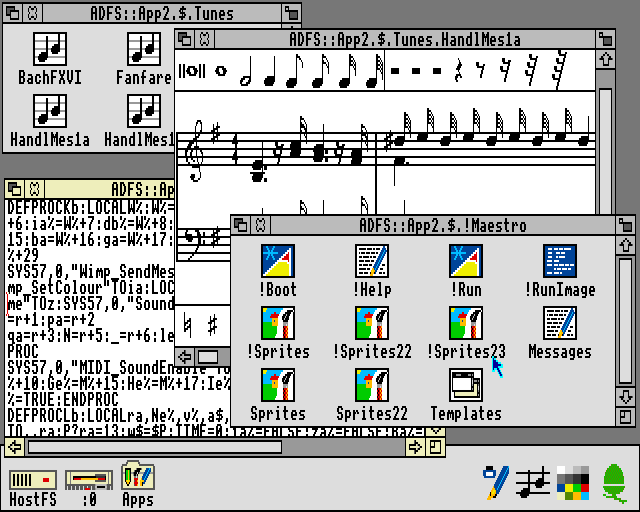

RISC OS exposed the tensions between the need for a more usable and generally accessible interface, potentially doing many things at once, and the desire to be able to get under the hood and poke around. It was possible to write desktop applications in BASIC, but this was not really done in a particularly interactive way, and programs needed to make system calls to interact with the rest of the desktop environment, even though the contents of windows were painted using the classic BASIC graphics primitives otherwise available to programs outside the desktop. Desktop programs were also expected to cooperate properly with each other, potentially hanging the system if not written correctly.

The Maestro music player in RISC OS, written in BASIC. Note that the !RunImage file is a BASIC program, with the somewhat compacted code shown in the text editor.

A safer option for those wanting the classic experience and to leverage their hard-earned knowledge, was to forget about the desktop and most of the newer capabilities of the Archimedes and to enter the BBC Micro emulator, 65Host, available on one of the supplied application disks, writing software just as before, and then running that software or any other legacy software of choice. Apart from providing file storage to the emulator and bearing all the work of the emulator itself, this did not really exercise the newer machine, but it still provided a largely authentic, traditional experience. One could presumably crash the emulated machine, but this should merely have terminated the emulator.

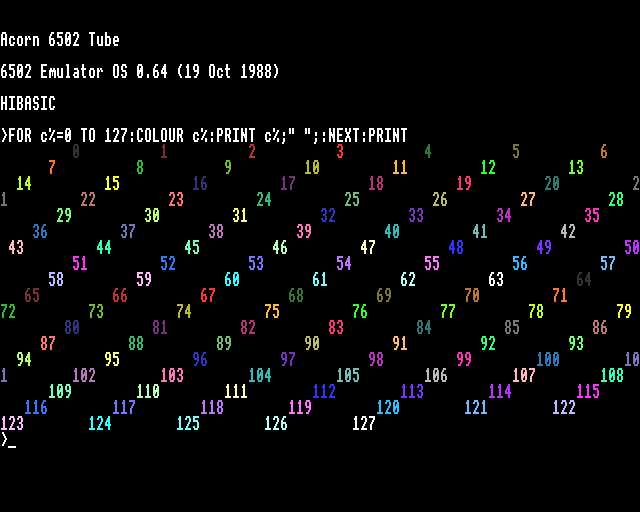

An intermediate form of legacy application support was also provided. 65Tube, with “Tube” referencing an interfacing paradigm used by the BBC Micro, allowed applications written against documented interfaces to run under emulation but accessing facilities in the native environment. This mostly accommodated things like programming language environments and productivity applications and might have seemed superfluous alongside the provision of a more comprehensive emulator, but it potentially allowed such applications to access capabilities that were not provided on earlier systems, such as display modes with greater resolutions and more colours, or more advanced filesystems of different kinds. Importantly, from an educational perspective, these emulators offered experiences that could be translated to the native environment.

65Tube running in MODE 15, utilising many more colours than normally available on earlier Acorn machines.

Although the Archimedes drifted away from the apparent simplicity of the BBC Micro and related machines, most users did not fully understand the software stack on such earlier systems, anyway. However, despite the apparent sophistication of the BBC Micro’s successors, various aspects of the software architecture were, in fact, preserved. Even the graphical user interface on the Archimedes was built upon many familiar concepts and abstractions. The difficulty for users moving up to the newer system arose upon finding that much of their programming expertise and effort had to be channelled into a software framework that confined the activities of their code, particularly in the desktop environment. One kind of framework for more advanced programs had merely been replaced by others.

Finding Lessons for Today

The way the Archimedes attempted to accommodate the expectations cultivated by earlier machines does not necessarily offer a convenient recipe to follow today. However, the solutions it offered should draw our attention to some other considerations. One is the level of safety in the environment being offered: it should be possible to interact with the system without bringing it down or causing havoc.

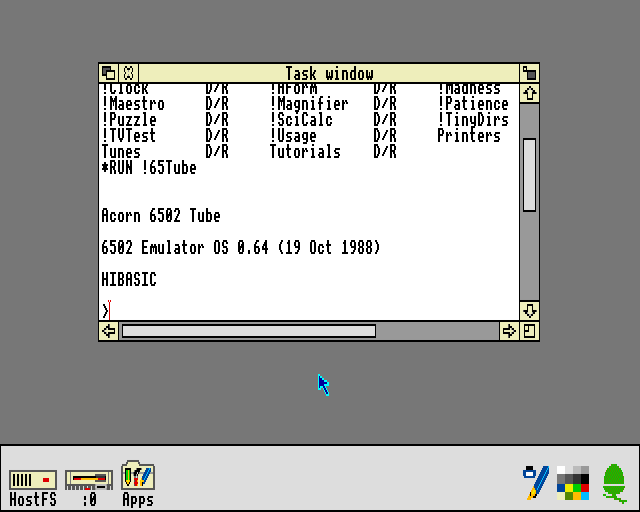

In that respect, the Archimedes provided a sandboxed environment like an emulator, but this was only really viable for running old software, as indeed was the intention. It also did not multitask, although other emulators eventually did. The more integrated 65Tube emulator also did not multitask, although later enhancements to RISC OS such as task windows did allow it to multitask to a degree.

65Tube running in a task window. This relies on the text editing application and unfortunately does not support fancy output.

Otherwise, the native environment offered all the familiar tools and the desired level of power, but along with them plenty of risks for mayhem. Thus, a choice between safety and concurrency was forced upon the user. (Aside from Arthur and RISC OS, there was also Acorn’s own Unix port, RISC iX, which had similar characteristics to the kind of Linux-based operating system typically run on the Pi. You could, in principle, run a BBC Micro emulator under RISC iX, just as people run emulators on the Pi today.)

Today, we could actually settle for the same software stack on some Raspberry Pi models, with all its advantages and disadvantages, by running an updated version of RISC OS on such hardware. The bundled emulator support might be missing, however, but for those wanting to go under the hood and also take advantage of the hardware, it is unlikely that they would be so interested in replicating the original BBC Micro experience with perfect accuracy, instead merely seeking to replicate the same kind of experience.

Another consideration the Archimedes raises is the extent to which an environment may take advantage of the host system, and it is this consideration that potentially has the most to offer in formulating modern solutions. We may normally be completely happy running a programming tool in our familiar computing environments, where graphical output, for example, may be confined to a window or occasionally shown in full-screen mode. Indeed, something like a Raspberry Pi need not have any rigid notion of what its “native” graphical capabilities are, and the way a framebuffer is transferred to an actual display is normally not of any real interest.

The learning and practice of high-level programming can be adequately performed in such a modern environment, with the user safely confined by the operating system and mostly unable to bring the system down. However, it might not adequately expose the user to those low-level “under the hood” concepts that they seem to be missing out on. For example, we may wish to introduce the framebuffer transfer mechanism as some kind of educational exercise, letting the user appreciate how the text and graphics plotting facilities they use lead to pixels appearing on their screen. On the BBC Micro, this would have involved learning about how the MOS configures the 6845 display controller and the video ULA to produce a usable display.

The configuration of such a mechanism typically resides at a fairly low level in the software stack, out of the direct reach of the user, but allowing a user to reconfigure such a mechanism would risk introducing disruption to the normal functioning of the system. Therefore, a way is needed to either expose the mechanism safely or to simulate it. Here, technology’s steady progression does provide some possibilities that were either inconvenient or impossible on an early ARM system like the Archimedes, notably virtualisation support, allowing us to effectively run a simulation of the hardware efficiently on the hardware itself.

Thus, we might develop our own framebuffer driver and fire up a virtual machine running our operating system of choice, deploying the driver and assessing the consequences provided by a simulation of that aspect of the hardware. Of course, this would require support in the virtual environment for that emulated element of the hardware. Alternatively, we might allow some kind of restrictive access to that part of the hardware, risking the failure of the graphical interface if misconfiguration occurred, but hopefully providing some kind of fallback control mechanism, like a serial console or remote login, to restore that interface and allow the errant code to be refined.

A less low-level component that might invite experimentation could be a filesystem. The MOS in the BBC Micro and related machines provided filesystem (or filing system) support in the form of service ROMs, and in RISC OS on the Archimedes such support resides in the conceptually similar relocatable modules. Given the ability of normal users to load such modules, it was entirely possible for a skilled user to develop and deploy their own filesystem support, with the associated risks of bringing down the system. Linux does have arguably “glued-on” support for unprivileged filesystem deployment, but there might be other components in the system worthy of modification or replacement, and thus the virtual machine might need to come into play again to allow the desired degree of experimentation.

A Framework for Experimentation

One can, however, envisage a configurable software system where a user session might involve a number of components providing the features and services of interest, and where a session might be configured to exclude or include certain typical or useful components, to replace others, and to allow users to deploy their own components in a safe fashion. Alongside such activities, a normal system could be running, providing access to modern conveniences at a keypress or the touch of a button.

We might want the flexibility to offer something resembling 65Host, albeit without the emulation of an older system and its instruction set, for a highly constrained learning environment where many aspects of the system can be changed for better or worse. Or we might want something closer to 65Tube, again without the emulation, acting mostly as a “native” program but permitting experimentation on a few elements of the experience. An entire continuum of possibilities could be supported by a configurable framework, allowing users to progress from a comfortable environment with all of the expected modern conveniences, gradually seeing each element removed and then replaced with their own implementation, until arriving in an environment where they have the responsibility at almost every level of the system.

In principle, a modern system aiming to provide an “under the hood” experience merely needs to simulate that experience. As long as the user experiences the same general effects from their interactions, the environment providing the experience can still isolate a user session from the underlying system and avoid unfortunate consequences from that misbehaving session. Purists might claim that as long as any kind of simulation is involved, the user is not actually touching the hardware and is therefore not engaging in low-level development, even if the code they are writing would be exactly the code that would be deployed on the hardware.

Systems programming can always be done by just writing programs and deploying them on the hardware or in a virtual machine to see if they work, resetting the system and correcting any mistakes, which is probably how most programming of this kind is done even today. However, a suitably configurable system would allow a user to iteratively and progressively deploy a customised system, and to work towards deploying a complete system of their own. With the final pieces in place, the user really would be exercising the hardware directly, finally silencing the purists.

Naturally, given my interest in microkernel-based systems, the above concept would probably rest on the use of a microkernel, with much more of a blank canvas available to define the kind of system we might like, as opposed to more prescriptive systems with monolithic kernels and much more of the basic functionality squirrelled away in privileged kernel code. Perhaps the only difficult elements of a system to open up to user modification, those that cannot also be easily delegated or modelled by unprivileged components, would be those few elements confined to the microkernel and performing fundamental operations such as directly handling interrupts, switching execution contexts (threads), writing memory mappings to the appropriate registers, and handling system calls and interprocess communications.

Even so, many aspects of these low-level activities are exposed to user-level components in microkernel-based operating systems, leaving few mysteries remaining. For those advanced enough to progress to kernel development, traditional systems programming practices would surely be applicable. But long before that point, motivated learners will have had plenty of opportunities to get “under the hood” and to acquire a reasonable understanding of how their systems work.

A Conclusion of Sorts

As for why people are not widely using the Raspberry Pi to explore low-level computing, the challenge of facilitating such exploration when the system has “other jobs to do” certainly seems like a reasonable excuse, especially given the choice of operating system deployed on most Pi devices. One could remove those “other jobs” and run RISC OS, of course, putting the learner in an unfamiliar and more challenging environment, perhaps giving them another computer to use at the same time to look things up on the Internet. Or one could adopt a different software architecture, but that would involve an investment in software that few organisations can be bothered to make.

I don’t know whether the University of Cambridge has seen better-educated applicants in recent years as a result of Pi proliferation, or whether today’s applicants are as similarly perplexed by low-level concepts as those from the pre-Pi era. But then, there might be a lesson to be learned about applying some rigour to technological interventions in society. After all, there were some who justifiably questioned the effectiveness of rolling out microcomputers in schools, particularly when teachers have never really been supported in their work, as more and more is asked of them by their political overlords. Investment in people and their well-being is another thing that few organisations can be bothered to make, too.

Dual Screen CI20

December 15th, 2024

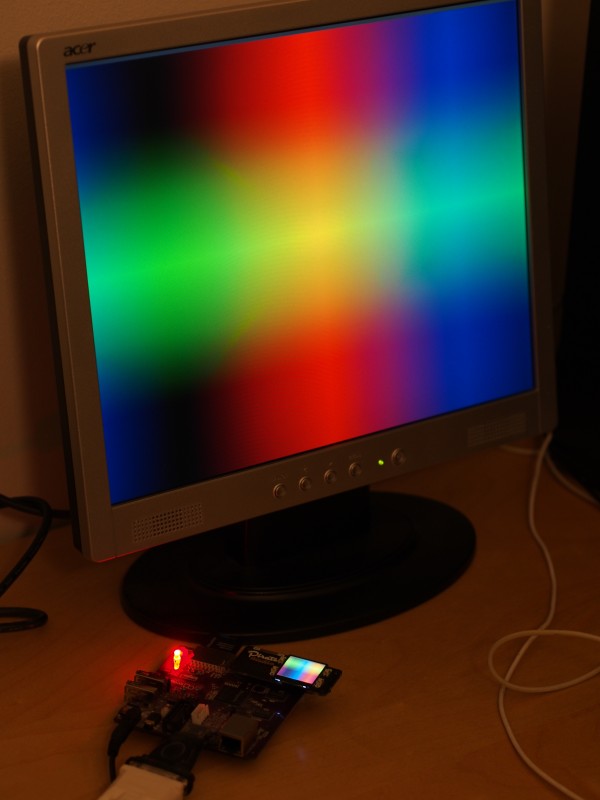

Following on from yesterday’s post, where a small display was driven over SPI from the MIPS Creator CI20, it made sense to exercise the HDMI output again. With a few small fixes to the configuration files, demonstrating that the HDMI output still worked, I suppose one thing just had to be done: to drive both displays at the same time.

The MIPS Creator CI20 driving an SPI display and a monitor via HDMI.

Thus, two separate instances of the spectrum example, each utilising their own framebuffer, potentially multiplexed with other programs (but not actually done here), are displayed on their own screen. All it required was a configuration that started all the right programs and wired them up.

Again, we may contemplate what the CI20 was probably supposed to be: some kind of set-top box providing access to media files stored on memory cards or flash memory, possibly even downloaded from the Internet. On such a device, developed further into a product, there might well have been a front panel display indicating the status of the device, the current media file details, or just something as simple as the time and date.

Here, an LCD is used and not in any sensible orientation for use in such a product, either. We would want to use some kind of right-angle connector to make it face towards the viewer. Once upon a time, vacuum fluorescent displays were common for such applications, but I could imagine a simple, backlit, low-resolution monochrome LCD being an alternative now, maybe with RGB backlighting to suit the user’s preferences.

Then again, for prototyping, a bright LCD like this, decadent though it may seem, somehow manages to be cheaper than much simpler backlit, character matrix displays. And I also wonder how many people ever attached two displays to their CI20.

Testing Newer Work on Older Boards

December 14th, 2024

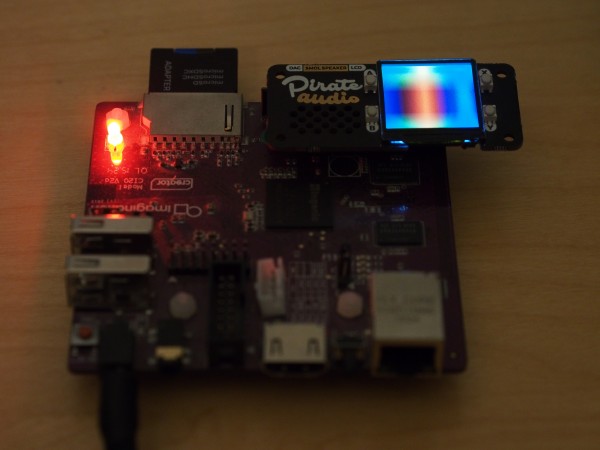

Since I’ve been doing some housekeeping in my low-level development efforts, I had to get the MIPS Creator CI20 out and make sure I hadn’t broken too much, also checking that the newer enhancements could be readily ported to the CI20’s pinout and peripherals. It turns out that the Pimoroni Pirate Audio speaker board works just fine on the primary expansion header, at least to use the screen, and doesn’t need the backlight pin connected, either.

The Pirate Audio speaker hat on the MIPS Creator CI20.

Of course, the CI20 was designed to be pinout-compatible with the original Raspberry Pi, which had a 26-pin expansion header. This was replaced by a 40-pin header in subsequent Raspberry Pi models, presumably wrongfooting various suppliers of accessories, but the real difficulties will have been experienced by those with these older boards, needing to worry about whether newer, 40-pin “hat” accessories could be adapted.

To access the Pirate Audio hat’s audio support, some additional wiring would, in principle, be necessary, but the CI20 doesn’t expose I2S functionality via its headers. (The CI20 has a more ambitious audio architecture involving a codec built into the JZ4780 SoC and a wireless chip capable of Bluetooth audio, not that I’ve ever exercised this even under Linux.) So, this demonstration is about as far as we can sensibly get with the CI20. I also tested the Waveshare panel and it seemed to work, too. More testing remains, of course!

A Small Update

December 6th, 2024

Following swiftly on from my last article, I decided to take the opportunity to extend my framebuffer components to support an interface utilised by the L4Re framework’s Mag component, which is a display multiplexer providing a kind of multiple window environment. I’m not sure if Mag is really supported any more, but it provided the basis of a number of L4Re examples for a while, and I brought it into use for my own demonstrations.

Eventually, having needed to remind myself of some of the details of my own software, I managed to deploy the collection of components required, each with their own specialised task, but most pertinently a SoC-specific SPI driver and a newly extended display-specific framebuffer driver. The framebuffer driver could now be connected directly to Mag in the Lua-based coordination script used by the Ned initialisation program, which starts up programs within L4Re, and Mag could now request a region of memory from the framebuffer driver for further use by other programs.

All of this extra effort merely provided another way of delivering a familiar demonstration, that being the colourful, mesmerising spectrum example once provided as part of the L4Re software distribution. This example also uses the programming interface mentioned above to request a framebuffer from Mag. It then plots its colourful output into this framebuffer.

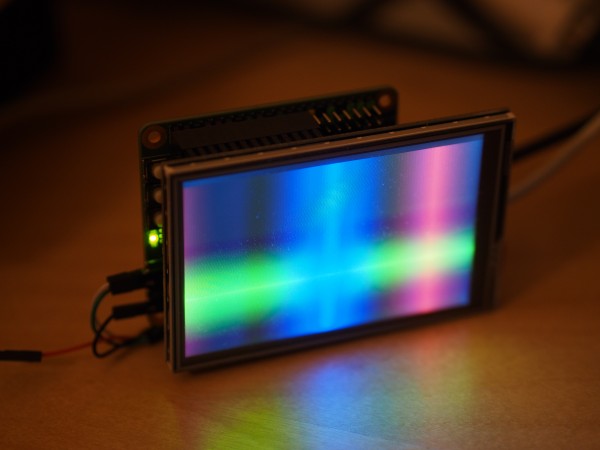

The result is familiar from earlier articles:

The spectrum example on a screen driven by the ILI9486 controller.

The significant difference, however, is that underneath the application programs, a combination of interchangeable components provides the necessary adaptation to the combination of hardware devices involved. And the framebuffer component can now completely replace the fb-drv component that was also part of the L4Re distribution, thereby eliminating a dependency on a rather cumbersome and presumably obsolete piece of software.

Recent Progress

December 2nd, 2024

The last few months have not always been entirely conducive to making significant progress with various projects, particularly my ongoing investigations and experiments with L4Re, but I did manage to reacquaint myself with my previous efforts sufficiently to finally make some headway in November. This article tries to retrieve some of the more significant accomplishments, modest as they might be, to give an impression of how such work is undertaken.

Previously, I had managed to get my software to do somewhat useful things on MIPS-based single-board computer hardware, showing graphical content on a small screen. Various problems had arisen with regard to one revision of a single-board computer for which the screen was originally intended, causing me to shift my focus to more general system functionality within L4Re. With the arrival of the next revision of the board, I leveraged this general functionality, combining it with support for memory cards, to get my minimalist system to operate on the board itself. I rather surprised myself getting this working, it must be said.

Returning to the activity at the start of November, there were still some matters to be resolved. In parallel to my efforts with L4Re, I had been trying to troubleshoot the board’s operation under Linux. Linux is, in general, a topic upon which I do not wish to waste my words. However, with the newer board revision, I had also acquired another, larger, screen and had been investigating its operation, and there were performance-related issues experienced under Linux that needed to be verified under other conditions. This is where a separate software environment can be very useful.

Plugging a Leak

Before turning my attention to the larger screen, I had been running a form of stress test with the smaller screen, updating it intensively while also performing read operations from the memory card. What this demonstrated was that there were no obvious bandwidth issues with regard to data transfers occurring concurrently. Translating this discovery back to Linux remains an ongoing exercise, unfortunately. But another problem arose within my own software environment: after a while, the filesystem server would run out of memory. I felt that this problem now needed to be confronted.

Since I tend to make such problems for myself, I suspected a memory leak in some of my code, despite trying to be methodical in the way that allocated objects are handled. I considered various tools that might localise this particular leak, with AddressSanitizer and LeakSanitizer being potentially useful, merely requiring recompilation and being available for a wide selection of architectures as part of GCC. I also sought to demonstrate the problem in a virtual environment, this simply involving appropriate test programs running under QEMU. Unfortunately, the sanitizer functionality could not be linked into my binaries, at least with the Debian toolchains that I am using.

Eventually, I resolved to use simpler techniques. Wondering if the memory allocator might be fragmenting memory, I introduced a call to malloc_stats, just to get an impression of the state of the heap. After failing to gain much insight into the problem, I rolled up my sleeves and decided to just look through my code for anything I might have done with regard to allocating memory, just to see if I had overlooked anything as I sought to assemble a working system from its numerous pieces.

Sure enough, I had introduced an allocation for “convenience” in one kind of object, making a pool of memory available to that object if no specific pool had been presented to it. The memory pool itself would release its own memory upon disposal, but in focusing on getting everything working, I had neglected to introduce the corresponding top-level disposal operation. With this remedied, my stress test was now able to run seemingly indefinitely.

Separating Displays and Devices

I would return to my generic system support later, but the need to exercise the larger screen led me to consider the way I had previously introduced support for screens and displays. The smaller screen employs SPI as the communications mechanism between the SoC and the display controller, as does the larger screen, and I had implemented support for the smaller screen as a library combining the necessary initialisation and pixel data transfer code with code that would directly access the SPI peripheral using a SoC-specific library.

Clearly, this functionality needed to be separated into two distinct parts: the code retaining the details of initialising and operating the display via its controller, and the code performing the SPI communication for a specific SoC. Not doing this could require us to needlessly build multiple variants of the display driver for different SoCs or platforms, when in principle we should only need one display driver with knowledge of the controller and its peculiarities, this then being combined using interprocess communication with a single, SoC-specific driver for the communications.

A few years ago now, I had in fact implemented a “server” in L4Re to perform short SPI transfers on the Ben NanoNote, this to control the display backlight. It became appropriate to enhance this functionality to allow programs to make longer transfers using data held in shared memory, all of this occurring without those programs having privileged access to the underlying SPI peripheral in the SoC. Alongside the SPI server appropriate for the Ben NanoNote’s SoC, servers would be built for other SoCs, and only the appropriate one would be started on a given hardware device. This would then mediate access to the SPI peripheral, accepting requests from client programs within the established L4Re software architecture.

One important element in the enhanced SPI server functionality is the provision of shared memory that can be used for DMA transfers. Fortunately, this is mostly a matter of using the appropriate settings when requesting memory within L4Re, even though the mechanism has been made somewhat more complicated in recent times. It was also fortunate that I previously needed to consider such matters when implementing memory card support, saving me time in considering them now. The result is that a client program should be able to write into a memory region and the SPI server should be able to send the written data directly to the display controller without any need for additional copying.

Complementing the enhanced SPI servers are framebuffer components that use these servers to configure each kind of display, each providing an interface to their own client programs which, in turn, access the display and provide visual content. The smaller screen uses an ST7789 controller and is therefore supported by one kind of framebuffer component, whereas the larger screen uses an ILI9486 controller and has its own kind of component. In principle, the display controller support could be organised so that common code is reused and that support for additional controllers would only need specialisations to that generic code. Both of these controllers seem to implement the MIPI DBI specifications.

The particular display board housing the larger screen presented some additional difficulties, being very peculiarly designed to present what would seem to be an SPI interface to the hardware interfacing to the board, but where the ILI9486 controller’s parallel interface is apparently used on the board itself, with some shift registers and logic faking the serial interface to the outside world. This complicates the communications, requiring 16-bit values to be sent where 8-bit values would be used in genuine SPI command traffic.