Paul Boddie's Free Software-related blog

Paul's activities and perspectives around Free Software

More on Kolab and Debian

October 23rd, 2013

Well, after my recent blog post highlighting some surprising problems with my Kolab installation – not at all a complaint about the packages, really, but more of a contribution towards improving the packaging situation, as I see it at least – some more interest in the situation around Kolab packaging for Debian has been shown:

- HowTo improve Debian packages using OBS describes the documented packaging-related process in more detail for a specific improvement.

- A Call for Participation invites those interested in Debian packaging to get involved.

Packaging for Debian can be a challenge. My own experience involved a pure-Python tool and still required lots of iterations to satisfy the Debian gatekeepers; this is understandable given that they try to virtually guarantee a coherent experience and provide a large selection of software whose copyright and licensing status must be clear, acceptable and without nasty surprises. I respect the effort that has gone into Kolab packaging for Debian already: without that effort, I probably wouldn’t even have tried the software.

The plan now must surely involve input from the Debian groupware initiative, especially as the Kolab architecture presumably resembles some of the other packaged solutions, and those who have contributed to the existing packaging work, as well as some discussion on the Kolab development mailing list, and some effort with the Open Build Service tools (with the “build commander” tool fortunately being available as a Debian package).

It is unfortunate that as Torsten points out, “Currently, there’s only one volunteer working on the Debian packages in his limited spare time, but hundreds of people who want to use reliable Debian packages.” Meanwhile, Timotheus points out, “Since there seems to be no corporate funding available for the Debian packages, we all need to pull together as a community and get it done!” It seems to me that those organisations that stand to benefit from more adoption of Free Software groupware, especially those using Debian as their foundation, might do well to assist this work instead of waiting for people to get it done in their free time.

Kolab and Debian Packaging Pitfalls

October 21st, 2013

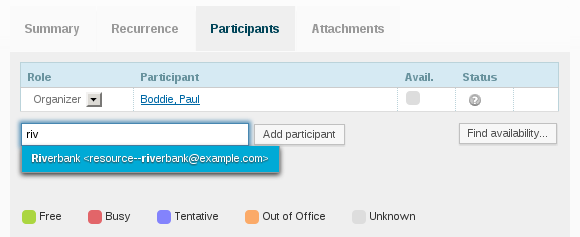

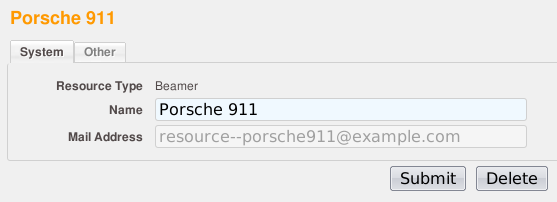

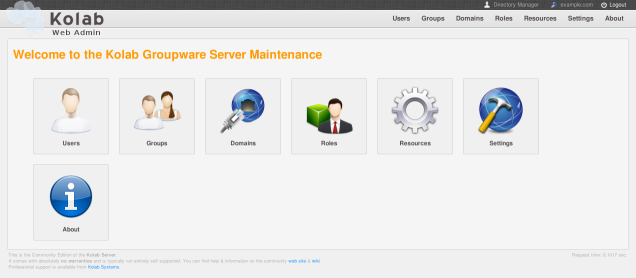

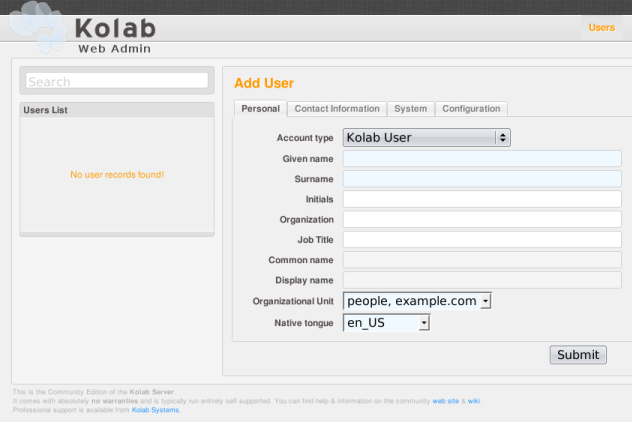

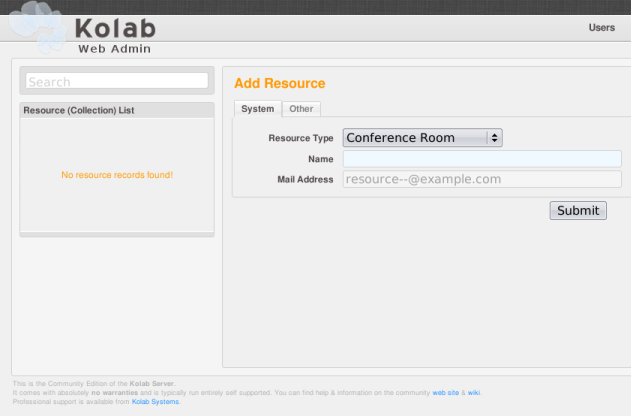

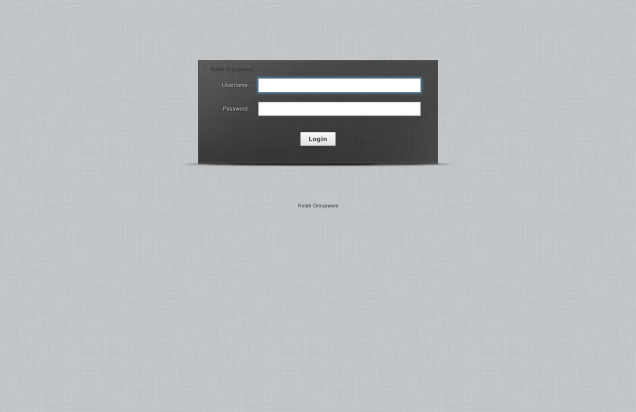

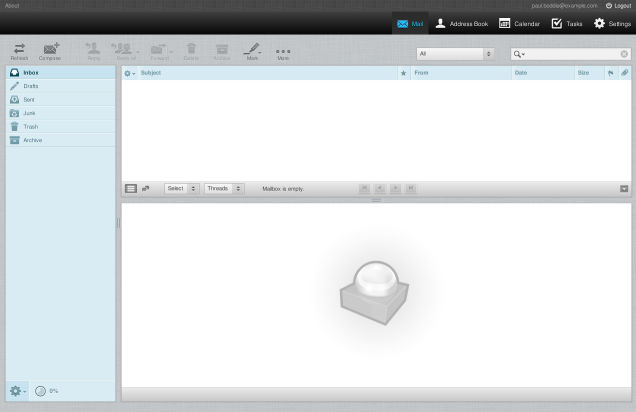

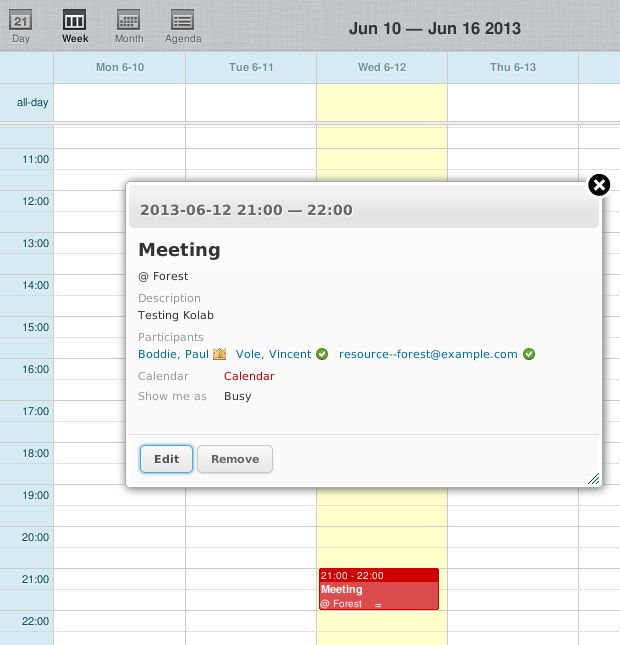

Hugo Roy has been trying to install Kolab and not getting on particularly well with it. His experiences persuaded me to take another look at my Kolab installation done back in June, and to my surprise it didn’t seem to work any more. I eventually discovered some things that will probably need fixing in the packaging, and these are mentioned below. I suppose I’ll try and pursue these with the developers and packagers.

The LDAP server (provided by the 389-ds suite of packages, but actually started when the ns-slapd program is run, and known as the dirsrv service – yes, all very confusing stuff) doesn’t want to run until the permissions are fixed on the /var/run/dirsrv and /var/lock/dirsrv directories so that the ns-slapd program can create pid and lock files.

The kolab-saslauthd service won’t be running if the LDAP server isn’t running. (You can check this using service --status-all and seeing what is running and what isn’t.) Some Kolab programs seem to get upset when they can’t connect to the LDAP or IMAP servers, and if the LDAP server is brought up, there’s a frequent, recurring error from a Python program complaining about IMAP server connections failing…

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/usr/lib/python2.7/dist-packages/kolabd/process.py", line 44, in synchronize

auth.synchronize()

File "/usr/lib/python2.7/dist-packages/pykolab/auth/__init__.py", line 243, in synchronize

self._auth.synchronize()

File "/usr/lib/python2.7/dist-packages/pykolab/auth/ldap/__init__.py", line 860, in synchronize

callback=self._synchronize_callback,

File "/usr/lib/python2.7/dist-packages/pykolab/auth/ldap/__init__.py", line 2151, in _search

secondary_domains

File "", line 10, in

File "/usr/lib/python2.7/dist-packages/pykolab/auth/ldap/__init__.py", line 1895, in _persistent_search

secondary_domains=secondary_domains

File "/usr/lib/python2.7/dist-packages/pykolab/auth/ldap/__init__.py", line 1735, in _synchronize_callback

eval("self._change_none_%s(entry, change_dict)" % (entry['type']))

File "", line 1, in

File "/usr/lib/python2.7/dist-packages/pykolab/auth/ldap/__init__.py", line 1389, in _change_none_user

self.imap.connect(domain=self.domain)

File "/usr/lib/python2.7/dist-packages/pykolab/imap/__init__.py", line 144, in connect

self._imap[hostname].login(admin_login, admin_password)

File "/usr/lib/python2.7/dist-packages/pykolab/imap/cyrus.py", line 133, in login

cyruslib.CYRUS.login(self, *args, **kw)

File "/usr/lib/python2.7/dist-packages/cyruslib.py", line 416, in login

self.__doexception("LOGIN", error)

File "/usr/lib/python2.7/dist-packages/cyruslib.py", line 359, in __doexception

self.__doraise( function.upper(), msg )

File "/usr/lib/python2.7/dist-packages/cyruslib.py", line 368, in __doraise

raise CYRUSError( idError[0], mode, msg )

CYRUSError: (10, 'LOGIN', 'generic failure')

Restarting the kolab-saslauthd service fixes this; maybe restarting the cyrus-imapd service also helps. Restarting the kolab-server service should apparently synchronise the constituent services, but I’m not sure it helps if you get the above Python error. You may also see an LDAP-related error which just appears to be the same program or a related one getting even more upset about the LDAP server.

Also, if you don’t update for a while, the clamav-freshclam service uses a lot of CPU and bandwidth performing updates. Such stuff needs turning off if you value your computer’s interactivity, in my experience.

Neo900: Combining Communities to Create Opportunities

September 10th, 2013

Ever since the withdrawal of Openmoko from open smartphone development, it appears to have been challenging to find large numbers of people who might be interested in supporting similar open hardware efforts, either by having them put down money to fund the development and production of devices, or by encouraging them to develop Free Software to run on the hardware produced by those efforts. That anyone can go and buy an Android phone and tell themselves that it is just like that dream they once had of running Linux on a phone (if they turn the lights down low enough and ignore the technical and ethical limitations) serves as just enough of a distraction to keep people merely curious about things like Openmoko and open hardware, persuading them to hold off supporting such things until everybody else has jumped on board and already made it a safe choice. It almost goes without saying that where risk-takers are needed to make something happen, that thing is not going to happen if everybody looks to everybody else to take the risk. (And even when people do take the risk, they seem to think that their pledges and donations are as good as money in the bank, but that is another story.)

Naturally, the Ubuntu Edge campaign showed that some money is floating around and can be attracted to suitably exciting projects. Unfortunately, one may be tempted to conclude that anything more mundane than a next generation product – one that can only be delivered at some point in the future, once it becomes feasible and economic to manufacture and sell something with “out of this world” specifications – is unlikely to attract the interest of potential customers with money to pledge towards something. Such potential customers surely want something their money cannot already buy, and offering only things like openness and freedom as enhancements to today’s specifications is perhaps not exciting enough for some of those people.

It is therefore rather refreshing that two communities have recently become more aware of the possibilities offered by, and available to, open hardware: the OpenPhoenux community with their ongoing GTA04 project to follow on from the work of Openmoko, and the Maemo community seeking a sustainable future beyond the now-discontinued Nokia N900 smartphone. Despite heroic efforts to sustain the GTA04 project, outside interest has apparently been low enough that additional production has been placed on hold: a minimum number of orders needs to exist before any kind of further manufacturing can take place. Meanwhile, a community of people whose devices may one day fail to function or perhaps no longer function already, forcing them to seek replacements in the second-hand market with all the usual online auction profiteering and the purchasing uncertainties that go along with it, have been made aware of an active hardware project whose foundations largely resemble those of the devices they wish to sustain.

So, unlike Ubuntu Edge, the Neo900 initiative is not offering next year’s hardware. In fact, it is not even offering this year’s hardware. But what it does offer is a sustainable path into the future for those who like the form factor and software provided by the N900: people who were having to come to terms with buying a device that would not be as satisfactory as the one they already have, merely because the device they already have has reached the end of its usable life, and because the mobile device industry has a different idea of progress from the one they happen to have. In effect, the Neo900 is about taking control, owning the roadmap, deciding when or whether the fads and fashions of the industry at large will serve them better, and being able to choose or to reject the wider industry’s offerings on a more reasonable timescale.

The N900, as a product abandoned some time ago by Nokia as it retreated into being a vassal state of the Microsoft empire, gets an opportunity to rise from the ashes of the ruin wrought by the establishment of that corporate relationship. At a time where Nokia sees its core business incorporated into Microsoft itself in the final chapter of what has to be one of the most widely predicted and reported acts of alleged corporate looting in recent years, and where former Nokia executives announce plans to re-establish the business independently by attracting neglected Nokia talent, the open phoenix in the form of OpenPhoenux may help the N900 to rise above its troubled past and to shine once again as its former custodians struggle with the mayhem of corporate integration or corporate reconstruction, depending on where they end up.

People might wonder why anyone would want more of the same rather than something new, different, exciting, shiny. The fact is that away from the noise of exhibition floor, trade show and developer conference demonstrations, most people just want something that works and, preferably, something they already know. Their life goes on and does not wait for them to have to learn the latest gestures and moves to make some new gadget do what their old gadget was doing before it broke down. Some people – those with an N900 or those who wanted one – now have a new opportunity available to them, thanks to open hardware and the Neo900 initiative. For the rest of us, it offers more choice and maybe some hope that open hardware will be able to cater to more people in times to come.

Terms of the Pirates

September 3rd, 2013

According to the privacy policy on the Web site of the UK Pirate Party, “The information generated by the cookie about your use of the website (including your IP address) will be transmitted to and stored by Google on servers in the United States.” Would it not be more appropriate for the pirates to do their own visitor analysis using a Free Software solution like Piwik?

Come on, pirates, you can do better than this!

Licensing in a Post Copyright World: Some Clarifications

July 28th, 2013

Every now and then, someone voices their dissatisfaction with the GNU General Public License (GPL). A recent example is the oddly titled Licensing in a Post Copyright World: odd because if anything copyright is getting stronger, even though public opposition to copyright legislation and related measures is also growing. Here I present some necessary clarifications for anyone reading the above article. This is just a layman’s interpretation, not legal advice.

Licence Incompatibility

It is no secret that code licensed only under specific versions of the GPL cannot be combined with code under other specific versions of the GPL such that the resulting combination will have a coherent and valid licence. But why are the licences incompatible? Because the decision was taken to strengthen the GPL in version 3 (GPLv3), but since this means adding more conditions to the licence that were not present in version 2 (GPLv2), and since GPLv2 does not let people who are not the authors of the code involved add new conditions, the additional conditions of GPLv3 cannot be applied to the “GPLv2 only” licensed code. Meanwhile, the “GPLv3 only” licensed code requires these additional conditions and does not allow people who are not the authors of the code to strip them away to make the resulting whole distributable under GPLv2. There are ways to resolve this as I mention below.

(There apparently was an initiative to make version 2.2 of the GPL as a more incremental revision of the licence, although incorporating AGPLv3 provisions, but according to one of the central figures in the GPL drafting activity, work progressed on GPLv3 instead. I am sure some people wouldn’t have liked the GPLv2.2 anyway, as the AGPLv3 provisions seem to be one of many things they don’t like.)

Unnecessary Amendments

Why is the above explanation about licence compatibility so awkward? Because of the “only” stipulation that people put on their code, against the advice of the authors of the licence. It turns out that some people have so little trust in the organisation that wrote the licence they have nevertheless chosen to use that in a flourish of self-assertion, they needlessly stipulate “only” instead of “or any later version” and feel that they have mastered the art of licensing.

So the problems experienced by projects who put “only” everywhere, becoming “stuck” on certain GPL versions is a situation of their own making, like someone seeing a patch of wet cement and realising that their handprint can be preserved for future generations to enjoy. Other projects suffer from such distrust, too, because even if they use “or any later version” to future-proof their licensing, they can be held back by the “only” crowd if they make use of that crowd’s software, rendering the licence upgrade option ineffective.

It is somewhat difficult to make licences that request that people play fair and at the same time do not require people to actually do anything to uphold that fairness, so when those who write the licences give some advice, it is somewhat impertinent to reject that advice and then to blame those very people for one’s own mistake later on. Even people who have done the recommended thing, but who suffer from “only” proliferation amongst the things on which their code depends should be blaming the people who put “only” everywhere, not the people who happened to write the licence in the first place.

A Political Movement

The article mentions that the GPL has become a “political platform”. But the whole notion of copyleft has been political from the beginning because it is all about a social contract between the developers and the end-users: not exactly the preservation of a monopoly on a creative work that the initiators of copyright had in mind. The claim is made that Apple shuns GPLv3 because it is political. In fact, companies like Apple and Nokia chiefly avoid GPLv3 because the patent language has been firmed up and makes those companies commit to not suing recipients of the code at will. (Nokia trumpeted a patent promise at one point, as if the company was exhibiting extreme generosity, but it turned out that they were obliged to license the covered patents because of the terms of GPLv2.) Apple has arguably only accepted the GPL in the past because the company could live with the supposed inconvenience of working with a wider development community on that community’s terms. As projects like WebKit have shown, even when obliged to participate under a copyleft licence, Apple can make collaboration so awkward that some participants (such as Google) would rather cultivate their own fork than deal with Apple’s obsession to control everything.

It is claimed that “the license terms are a huge problem for companies”, giving the example of Apple wanting to lock down their products and forbid anyone from installing anything other than Apple-approved software on devices that they have paid for and have in their own possession, claiming that letting people take control of their devices would obligate manufacturers to “get rid of the devices’ security systems”. In fact, it is completely possible to give the choice to users to either live with the restrictions imposed by the vendor and be able to access whichever online “app” store is offered by that vendor, or to let those users “root” or “jailbreak” their device and to tell them that they must find other sources of software and content. Such choices do not break any security systems at all, or at least not ones that we should be caring very much about.

People like to portray the FSF as being inflexible and opposed to the interests of businesses. However, the separation of the AGPL and the GPL contradicts such convenient assertions. Meanwhile, the article seems to suggest that we should blame the GPL for Apple’s inflexibility, which is, of course, absurd.

Blaming the Messenger

The article blames the AGPLv3 for the proliferation of “open core” business models. Pointing the finger at the licence and blaming it for the phenomenon is disingenuous since one could very easily concoct a licence that requires people to choose either no-cost usage, where they must share their code, or paid usage, where they get to keep their code secret. The means by which people can impose such a choice is their ownership of the code.

Although people can enforce an “open core” model more easily using copyleft licensing as opposed to permissive licensing, this is a product of the copyright ownership or assignment regime in place for a project, not something that magically materialises because a copyleft licence was chosen. It should be remembered that copyleft licences effectively regulate and work best with projects having decentralised ownership. Indeed, people have become more aware of copyright and licensing transfers and assignments perhaps as a result of “open core” business models and centralised project ownership, and they should be distrustful of commercial entities wanting such transfers and assignments to be made, regardless of any Free Software licence chosen, because they designate a privileged status in a project. Skepticism has even been shown towards the preference that projects transfer enforcement rights, if not outright ownership, to the FSF. Such skepticism is only healthy, even if one should probably give the FSF the benefit of the doubt as to the organisation’s intentions, in contrast to some arbitrary company who may change strategy from quarter to quarter.

The article also blames the GPLv3 or the AGPLv3 for the behaviour of “licence trolls”, but this is disingenuous. If Oracle offers a product with a choice of AGPLv3 or a special commercial licence, and if as a consequence those who want permissively licensed software for use in their proprietary products cannot get such software under permissive licences, it is the not the fault of any copyleft licence for merely existing: it is the fault (if this is even a matter of blame) of those releasing the software and framing the licence choices. Again, you do not need the FSF’s copyleft licences to exist to offer customers a choice of paying money or making compromises on how they offer their own work.

Of course, if people really cared about the state of projects that have switched licences, they would step up and provide a viable fork of the code starting from a point just before the licence change, but as can often be the case with permissively licensed software and a community of users dependent on a strong vendor, most people who claim to care are really looking for someone else to do the work so that they can continue to enjoy free gifts with as few obligations attached as possible. There are permissively licensed software projects with vibrant development communities, but remaining vibrant requires people to cooperate and for ownership to be distributed, if one really values community development and is not just looking for someone with money to provide free stuff. Addressing fundamental matters of project ownership and governance will get you much further than waving a magic wand and preferring permissive licensing, because you will be affected by those former things whichever way you decide to go with the latter.

Defining the New Normal

The article refers to BusyBox being “infamous” for having its licence enforced. That is a great way of framing reasonable behaviour in such a way as to suggest that people must be perverse for wanting to stand behind the terms under which, and mechanisms through which, they contributed their effort to a project. What is perverse is choosing a licence where such terms and mechanisms are defined and then waiving the obligation to defend it: it would not only be far easier to just choose another licence instead, but it would also be more honest to everyone wanting to use that project as well as everyone contributing to the project, too. The former group would have legal clarity and not the nods and winks of the project leadership; the latter group would know not to waste their time most likely helping people make proprietary software, if that is something they object to.

Indeed, when people contribute to a project it is on the basis of the social contract of the licence. When the licence is a copyleft licence, people will care whether others uphold their obligations. Some people say that they do not want the licence enforced on a project they contribute to. They have a right to express their own preference, but they cannot speak for everyone else who contributed under the explicit social contract that is the licence. Where even one person who has a contribution to a project sees their code used against the terms of the licence, that person has the right to demand that the situation be remedied. Denying individuals such rights because “they didn’t contribute very much” or “the majority don’t want to enforce the licence” (or even claiming that people are “holding the project to ransom”) sets a dangerous precedent and risks making the licence unenforceable for such projects as well as leaving the licence itself as a worthless document that has nothing to say about the culture or functioning of the project.

Some people wonder, “Why do you care what people do with your code? You have given it away.” Firstly, you have not given it away: you have shared it with people with the expectation that they will continue to share it. Copyleft licensing is all about the rights of the end-user, not about letting people do what they want with your code so that the end-user gets a binary dropped in their lap with no way of knowing what it is, what it does, or having any way of enjoying the rights given to the people who made that binary. As smartphone purchasers are discovering, binary-only shipments lead to unsustainable computing where devices are made obsolete not by fundamental changes in technology or physical wear and tear but by the unavailability of fixed, improved or maintained software that keep such devices viable.

Agreeing on the Licence

Disregarding the incompatibility between GPL versions, as discussed above, it appears more tempting to blame the GPL for situations of GPL-incompatibility than it does to blame other licences written after GPLv2 for causing such incompatibility in the first place. The article mentions that Sun deliberately made the CDDL incompatible with the GPL, presumably because they did not want people incorporating Solaris code into the GNU or Linux projects, thus maintaining that “competitive edge”. We all know how that worked out for Solaris: it can now be considered a legacy platform like AIX, HP-UX, and IRIX. Those who like to talk up GPL incompatibilities also like to overlook the fact that GPLv3 provides additional compatibility with other licences that had not been written in a GPLv2-compatible fashion.

The article mentions MoinMoin as being affected by a need for GPLv2 compatibility amongst its dependencies. In fact, MoinMoin is licensed under the GPLv2 or any later version, so those combining MoinMoin with various Apache Software Licence 2.0 licensed dependencies could distribute the result under GPLv3 or any later version. For those projects who stipulated GPLv2 only (against better advice) or even ones who just want the choice of upgrading the licence to GPLv3 or any later version, it is claimed that projects cannot change this largely because the provenance of the code is frequently uncertain, but the Mercurial project managed to track down contributors and relicensed to GPLv2 or any later version. It is a question of having the will and the discipline to achieve this. If you do not know who wrote your project’s code, not even permissive licences will protect you from claims of tainted code, should such claims ever arise.

The Fear Factor

Contrary to popular belief, all licences require someone to do (or not do) something. When people are not willing to go along with what a licence requires, we get into the territory of licence violation, unless people are taking the dishonest route of not upholding the licence and thus potentially betraying their project’s contributors. And when people fall foul of the licence, either inadvertently or through dishonesty, people want to know what might happen next.

It is therefore interesting that the article chooses to dignify claims of a GPL “death penalty”, given that such claims are largely made by people wanting to scare off others from Free Software, as was indeed shown when there may have been money and reputations to be made by engaging in punditry on the Google versus Oracle case. Not only have the actions taken to uphold the GPL been reasonable (contrary to insinuations about “infamous” reputations), but the licence revision process actually took such concerns seriously: version 3 of the GPL offers increased confidence in what the authors of the GPL family of licences actually meant. Obviously, by shunning GPLv3 and stipulating GPLv2 “only”, recipients of code licensed in such a way do not get the benefit of such increased clarity, but it is still likely that the fact that the licence authors sought to clarify such things may indeed weigh on interpretations of GPLv2, bringing some benefit in any case.

The Scapegoat

People like to invoke outrage by mentioning Richard Stallman’s name and some of the things he has said. Unfortunately for those people, Stallman has frequently been shown to be right. Interestingly, he has been right about issues that people probably did not consider to be of serious concern at the time they were raised, so that mentions of patents in GPLv2 not only proved to be far-sighted and useful in ensuring at least a workable level of protection for Free Software developers, but they also alerted Free Software communities, motivated people to resist patent expansionism, and predicted the unfortunate situation of endless, costly litigation that society currently suffers from. Such things are presumably an example of “specific usecases that were relevant at the time the license was written” according to the article, but if licence authors ignore such things, others may choose to consider them and claim some freedom in interpreting the licence on their behalf. In any case, should things like patents and buy-to-rent business models ever become extinct, a tidying up of the licence text for those who cannot bear to be reminded of them will surely do just fine.

Especially certain elements in the Python community seem to have a problem with Stallman and copyleft licensing, some blaming disagreements with, and the influence of, the FSF during the Python 1.6 licensing fiasco where the FSF rightly pointed out that references to venues (“Commonwealth of Virginia”) and having “click to accept” buttons in the licence text (with implicit acceptance through usage) would cause problems. Indeed, it is all very well lamenting that the interactions of licences with local law is not well understood, but one would think that where people have experience with such matters, others might choose to listen to such opinions.

It is a misrepresentation of Stallman’s position to claim that he wants strong copyright, as the article claims: in fact, he appears to want a strengthening of the right to share; copyleft is only a strategy to achieve this in a world with increasingly stronger copyright legislation. His objections to the Swedish Pirate Party’s proposals on five year copyright terms merely follow previous criticisms of additional instruments – in this case end-user licence agreements (EULAs) – that allow some parties to circumvent copyright restrictions on other people’s work whilst imposing additional restrictions – in previous cases, software patents – on their own and others’ works. Finding out what Stallman’s real position might require a bit of work, but it isn’t secret and in fact even advocates significantly reduced copyright terms, just as the Pirate Party advocates. If one is going to describe someone else’s position on a topic, it is best not to claim anything at all if the alternative is to just make stuff up instead.

The article ramps up the ridicule by claiming that the FSF itself claims that “cloud computing is the devil, cell phones are exclusively tracking devices”. Ridiculing those with legitimate concerns about technology and how it is used builds a culture of passive acceptance that plays into the hands of those who will exploit public apathy to do precisely what people labelled as “paranoid” or “radical” had warned everyone about. Recent events have demonstrated the dangers of such fashionable and conformist ridicule and the complacency it builds in society.

All Things to All People

Just as Richard Stallman cannot seemingly be all things to all people – being right about things like the threat of patents, for example, is just so annoying to those who cannot bring themselves to take such matters seriously – so the FSF and the GPL cannot be all things to all people, either. But then they are not claiming to be! The FSF recognises other software licences as Free Software and even recommends non-copyleft licences from time to time.

For those of us who prefer to uphold the rights of the end-user, so that they may exercise control over their computing environment and computing experience, the existence of the GPL and related copyleft licences is invaluable. Such licences may be complicated, but such complications are a product of a world in which various instruments are available to undermine the rights of the end-user. And defining a predictable framework through which such licences may be applied is one of the responsibilities that the FSF has taken upon itself to carry out.

Indeed, few other organisations have been able to offer what the FSF and closely associated organisations have provided over the years in terms of licensing and related expertise. Maybe such lists of complaints about the FSF or the GPL are a continuation of the well-established advertising tradition of attacking a well-known organisation to make another organisation or its products look good. The problem is that nobody really looks good as a result: people believe the bizarre insinuations of political propaganda and are less inclined to check what the facts say on whichever matter is being discussed.

People are more likely to make bad choices when they have only been able to make uninformed choices. The article seeks to inform people about some of the practicalities of licence compatibility but overemphasises sources with an axe to grind – and, in some cases, sources with rather dubious motivations – that are only likely to drive people away from reliable sources of information, filling the knowledge gap of the reader with innuendo from third parties instead. If the intention is to promote permissive licensing or merely licences that are shorter than the admittedly lengthy GPL, we would all be better served if those wishing to do so would stick to factual representations of both licensing practice and licence author intent.

And as for choosing a licence, some people have considered such matters before. Seeking to truly understand licences means having all the facts on the table, not just the ones one would like others to consider combined with random conjecture on the subject. I hope I have, at least, brought some of the missing facts to the table.

Ubuntu Edge: Making Things Even Harder for Open Hardware?

July 24th, 2013

The idea of a smartphone supportive of Free Software, using hardware that can be supported using Free Software, goes back a few years. Although the Openmoko Neo 1973 attracted much attention back in 2007, not only for its friendliness to Free Software but also for the openness around its hardware design, the Trolltech Greenphone had delivered, almost a full year before the Neo, a hardware platform that ran mostly Free Software and was ultimately completely supported using entirely Free Software (something that had been a matter of some earlier dispute). Unfortunately, both of these devices were discontinued fairly quickly: the Greenphone was more a vehicle to attract interest in the Qt-based Qtopia environment amongst developers, existing handset manufacturers and operators, and although the Neo 1973 was superseded by the Neo FreeRunner, the commercial partner of the endeavour eventually chose to abandon development of the platform and further products of this nature. (Openmoko now sells a product called WikiReader, which is an intriguing concept in itself, principally designed as an offline reader for Wikipedia.)

What survived the withdrawal of Openmoko from the pursuit of the Free Software smartphone was the community or communities around such work, having taken an active interest in developing software for such devices and having seen the merits of being able to influence the design of such devices through the principles of open hardware. Some efforts were made to continue the legacy: the GTA04 project develops and offers replacement hardware for the FreeRunner (known as GTA02 within the Openmoko project) using updated and additional components; a previous “gta02-core” effort attempted to refine the development process and specification of a successor to the FreeRunner but did not appear to produce any concrete devices; a GTA03 project which appeared to be a more participative continuation of the previous work, inviting the wider community into the design process alongside those who had done the work for the previous generations of Neo devices, never really took off other than to initiate the gta02-core effort, perhaps indicating that as the commercial sponsor’s interest started to vanish, the community was somewhat unreasonably expected to provide the expertise withdrawn by the sponsor (which included a lot of the hardware design and manufacturing expertise) as well as its own. Nevertheless, there is a degree of continuity throughout the false starts of GTA03 and gta02-core through to GTA04 and its own successes and difficulties today.

Then and Now

A lot has happened in the open hardware world since 2007. Platforms like Arduino have become very popular amongst electronics enthusiasts, encouraging the development of derivatives, clones, accessories and an entire marketplace around experimentation, prototyping and even product development. Other long-established microcontroller-based solution vendors have presumably benefited from the level of interest shown towards Arduino and other “-duino” products, too, even if those solutions do not give customers the right to copy and modify the hardware as Arduino does with its hardware licensing. Access to widely used components such as LCD panels has broadened substantially with plenty of reasonably priced products available that can be fairly easily connected to devices like the Arduino, BeagleBoard, Raspberry Pi and many others. Even once-exotic display technologies like e-paper are becoming accessible to individuals in the form of ready-to-use boards that just plug into popular experimenter platforms.

Meanwhile, more sophisticated parts of the open hardware world have seen their own communities develop in various ways. One community emerging from the Openmoko endeavour was Qi-Hardware, supported by Sharism who acquired the rights to produce the Ben NanoNote from the vendor of an existing product, thus delivering a device with completely documented electronics hardware, every aspect of which can be driven by Free Software. Unfortunately, efforts to iterate on the concept stalled after attempts to make improved revisions of the Ben, presumably in preparation to deliver future versions of the NanoNote concept. Another project founded under the Qi-Hardware umbrella has been extending the notion of “copyleft hardware” to system on a chip (SoC) solutions and delivering the Milkymist platform in the shape of the Milkymist One video synthesizer. Having dealt with commercially available but proprietary SoC solutions, such as the SoC used in the Ben NanoNote, there appears to be a desire amongst some to break free of the dependency on silicon vendors and their often poorly documented products and to take control not only of the hardware using Free Software tools, but also to decide how the very hardware platform itself is designed and built.

There are plenty of other hardware development initiatives taking place – OpenPandora, the EOMA-68 initiative, the Vivaldi KDE tablet (which is now going to be based on EOMA-68 hardware), the Novena open laptop – many of which have gained plenty of experience – sometimes very hard-earned experience – in getting hardware designed and produced. Indeed, the history of the Vivaldi initiative seems to provide a good illustration of how lessons that others have already learned are continuing to be learned independently: having negotiated manufacturing whilst suffering GPL-violating industry practices, the manufacturer changed the specification and rendered a lot of the existing work useless (presumably the part supporting the hardware with Free Software drivers).

In short, if you are considering designing a device “to run Linux”, the chances are that someone else is already doing just that. When people suggest that you look at various other projects or initiatives, they are not doing so to inflate the reputation of those projects: it is most likely the case that people associated with those projects can give you advice that will save you time and effort, even if there is no further collaboration to be had beyond exchanges of useful information.

The Competition for Attention

Ubuntu Edge – the recently announced, crowd-funded “dockable” smartphone – emerges at a time when there are already many existing open hardware projects in need of funding. Those who might consider supporting such worthy efforts may be able to afford supporting more than one of them, but they may find it difficult to justify doing so. Precious few details exist of the hardware featured in the Ubuntu Edge product, and it would be reasonable to suspect given the emphasis on specifications and features that it will not be open hardware. Moreover, given the tendency of companies wishing to enter the smartphone market to do so as conveniently as possible by adopting the “chipset of the month”, combined with the scarcity of silicon favouring true Free Software support, we might also suspect that the nature of the software support will be less than what we should be demanding: the ability to modify and maintain the software in order to use the hardware indefinitely and independently of the vendor.

Meanwhile, other worthy projects beyond the open hardware realm compete for the money of potential sponsors and donors. The Fairphone initiative has also invited people to pledge money towards the delivery of devices, although in a more tangible fashion than Ubuntu Edge, with genuine plans having been made for raw materials sourcing and device manufacture, and with software development supposedly undertaken on behalf of the project. As I noted previously, there are some unfortunate shortcomings with the Fairphone initiative around the openness of the software, and unless the participants are able to change the mindset of the chipset vendor and the suppliers of various technologies incorporated into the chipset, sustainable Free Software support may end up being dependent on reverse-engineering efforts. Mozilla’s Firefox OS, meanwhile, certainly emphasises a Free Software stack along with free and open standards, but the status of the software support for certain hardware functions are likely to be dependent on the details of the actual devices themselves.

Interest in open phones is not new, nor even is interest in “dockable” smartphones, and there are plenty of efforts to build elements of both while upholding Free Software support and even the principles of open hardware. Meanwhile, the Ubuntu Edge campaign provides no specifics about the details of the hardware; it is thus unable to make any commitment about Free Software drivers or binary firmware “blobs”. Maybe the intention is to one day provide things like board layouts and case designs as resources for further use and refinement by the open hardware community, but the recent track-record of Canonical and Ubuntu with secretive and divisive – or at least not particularly transparent or cooperative – product development suggests that this may be too much to hope.

Giving the Gift

$32 million is a lot of money. Broken into $600 chunks with the reward of the advertised device, or a consolation prize of your money back minus a few percent in fees and charges if the fund-raising campaign fails to reach its target, it is a lot of money for an individual, too. (There is also the worst-case eventuality that the target is met but the product is not delivered, at which point everybody might have found that they have merely made a donation towards a nice but eventually unrealisable or undeliverable idea.) One could do quite a bit of good work with even small multiples of $600, and with as much as around 0.5% of the Ubuntu Edge campaign target, one could fund something like the GCW Zero. That might not aggressively push back the limits of mobile technology on every front, but it gives people something different and valuable to them while still leaving plenty of money floating around looking for a good cause.

But it is not merely about the money, even though many of those putting down money for the Ubuntu Edge are likely to have ruled out doing the same for the Fairphone (and perhaps some of those who have ordered their Fairphone regret placing their order now that the Ubuntu Edge has made its appearance), purely because they neither need nor can reasonably afford or justify buying two new smartphones for delivery at some point in the future. The other gift that could be given is collaboration and assistance to the many projects already out there toiling to put Linux on some SoC or other, developing an open hardware design for others to use and improve, and deepening community expertise that might make these challenges more tolerable in the future.

Who knows how the Ubuntu Edge will be developed if or when the funding target is reached, or regardless of it being reached? But imagine what it would be like if such generosity could be directed towards existing work and if existing and new projects were able to work more closely with each other; if the expertise in different projects could be brought in to make some new endeavour more likely to succeed and less fraught with problems; if communities were included, encouraged to participate, and encouraged to take their own work further to enrich their own project and improve any future collaborations.

Investing, not Purchasing

$32 million is a lot of money. Less exciting things (to the average gadget buyer) like the OpenRISC funding drive to produce an ASIC version of an open hardware SoC wanted only $250000 – still a lot of money, but less than 1% of the Ubuntu Edge campaign target – and despite the potential benefits for both individuals and businesses it still fell far short of the mark, but if such projects were funded they might open up opportunities that do not exist now and would probably still not exist if Ubuntu got their product funded. And there are plenty of other examples where donations are more like investments in a sustainable future instead of one-off purchases of nice-looking gadgets.

Those thinking about making a Free Software phone might want to check in with the GTA04 project to see if there is anything they can learn or help out with. Similarly, that project could perhaps benefit from evaluating the EOMA-68 initiative which in turn could consider supporting genuinely open SoCs (and also removing the uncertainty about patent assertion for participants in the initiative by providing transparent governance mechanisms and not relying on the transient goodwill of the current custodians). As expertise is shared and collaboration increases, the money might start to be spread around a bit more as well, and cash-starved projects might be able to do things before those things become less interesting or even irrelevant because the market has moved on.

We have to invest both financially and collaboratively in the good work already taking place. To not do so means that opportunities that are almost within our grasp are not seized, and that people who have worked hard to offer us such opportunities are let down. We might lose the valuable expertise of such people through pure disillusionment, and yet the casual observer might still wonder when we might see the first fully open, Free Software friendly, mass-market-ready smartphone, thinking it is simply beyond “the community” to deliver. In fact, we might be letting the opportunity to deliver such things pass us by more often than we realise, purely out of ignorance of the ongoing endeavours of the community.

Diversions and Distractions

Ubuntu Edge sounds exciting. It is just a shame that it does not appear to enable and encourage everyone who has already been working to realise such ambitions on substantially lower budgets and with less of a brand reputation to cultivate the interest of the technology media and enthusiastic consumers. Millions of dollars of committed funds and an audience preferring to take the passive position of expectant customers, as opposed to becoming active contributors to existing efforts, all adds up to a diversion of participation and resources from open hardware projects.

Such blockbuster campaigns may even distract from open hardware projects because for those who might need slight persuasion to get involved, the apparition of an easy solution demanding only some spare cash and no intellectual investment may provide the discouragement necessary to affirm that as with so many other matters, somebody else has got them covered. Consequently, such people retreat from what might have been a rewarding pursuit that deepens their understanding of technology and the issues around it.

Not everyone has the time or inclination to get involved with open hardware, of course, especially if they are starting with practically no knowledge of the field. But with many people and their green pieces of paper parked and waiting for Ubuntu Edge, it is certainly possible to think that the campaign might make things even harder for the open hardware movement to get the recognition and the traction it deserves.

Students: Beware of the Academic Cloud!

July 21st, 2013

Things were certainly different when I started my university degree many years ago. For a start, institutions of higher education provided for many people their first encounter with the Internet, although for those of us in the United Kingdom, the very first encounter with wide area networking may well have involved X.25 and PAD terminals, and instead of getting a “proper” Internet e-mail address, it may have been the case that an address only worked within a particular institution. (My fellow students quickly became aware of an Internet mail gateway in our department and the possibility, at least, of sending Internet mail, however.)

These days, students beginning their university studies have probably already been using the Internet for most of their lives, will have had at least one e-mail address as well as accounts for other online services, may be publishing blog entries and Web pages, and maybe even have their own Web applications accessible on the Internet. For them, arriving at a university is not about learning about new kinds of services and new ways of communicating and collaborating: it is about incorporating yet more ways of working online into their existing habits and practices.

So what should students expect from their university in terms of services? Well, if things have not changed that much over the years, they probably need a means of communicating with the administration, their lecturers and their fellow students, along with some kind of environment to help them do their work and provide things like file storage space and the tools they won’t necessarily be able to provide themselves. Of course, students are more likely to have their own laptop computer (or even a tablet) these days, and it is entirely possible that they could use that for all their work, subject to the availability of tools for their particular course, and since they will already be communicating with others on the Internet, communicating with people in the university is not really anything different from what they are already doing. But still, there are good reasons for providing infrastructure for students to use, even if those students do end up working from their laptops, uploading assignments when they are done, and forwarding their mail to their personal accounts.

The Student Starter Kit

First and foremost, a university e-mail account is something that can act as an official communications channel. One could certainly get away with using some other account, perhaps provided by a free online service like Google or Yahoo, but if something went wrong somewhere – the account gets taken over by an imposter and then gets shut down, for example – that channel of communication gets closed and important information may be lost.

The matter of how students carry out their work is also important. In computer science, where my experiences come from and where computer usage is central to the course, it is necessary to have access to suitable tools to undertake assignments. As everyone who has used technology knows, the matter of “setting stuff up” is one that often demands plenty of time and distracts from the task at hand, and when running a course that requires the participants to install programs before they can make use of the learning materials, considerable amounts of time are wasted on installing programs and troubleshooting. Thus, providing a ready-to-use environment allows students to concentrate on their work and to more easily relate to the learning materials.

There is the matter of the nature of teaching environments and the tools chosen. Teaching environments also allow students to become familiar with desirable practices when finding solutions to the problems in their assignments. In software engineering, for example, the use of version control software encourages a more controlled and rational way of refining a program under development. Although the process itself may not be recognised and rewarded when an assignment is assessed, it allows students to see how things should be done and to take full advantage of the opportunity to learn provided by the institution.

Naturally, it should be regarded as highly undesirable to train students to use specific solutions provided by selected vendors, as opposed to educating them to become familiar with the overarching concepts and techniques of a particular field. Schools and universities are not vocational training institutions, and they should seek to provide their students with transferable skills and knowledge that can be applied generally, instead of taking the easy way out and training those students to perform repetitive tasks in “popular” software that gives them no awareness of why they are doing those things or any indication that the rest of the world might be doing them in other ways.

Minority Rule

So even if students arrive at their place of learning somewhat equipped to learn, communicate and do their work, there may still be a need for a structured environment to be provided for them. At that place of learning they will join those employed there who already have a structured environment in place to be able to do their work, whether that is research, teaching or administration. It makes a certain amount of sense for the students to join those other groups in the infrastructure already provided. Indeed, considering the numbers of people involved, with the students outnumbering all other groups put together by a substantial margin, one might think that the needs of the students would come first. Sadly, things do not always work that way.

First of all, students are only ever “passing through”. While some university employees may be retained for similar lengths of time – especially researchers and others on temporary contracts (a known problem with social and ethical dimensions of its own) – others may end up spending most of their working life there. As a result, the infrastructure is likely to favour such people over time as their demands are made known year after year, with any discomfort demanding to be remedied by a comfortable environment that helps those people do their work. Not that there is anything wrong with providing employees with a decent working environment: employers should probably do even more to uphold their commitments in this regard.

But when the demands and priorities of a relatively small group of people take precedence over what the majority – the students – need, one can argue that such demands and priorities have begun to subvert the very nature of the institution. Imposing restrictions on students or withholding facilities from them just to make life easier for the institution itself is surely a classic example of “the tail wagging the dog”. After all, without students and teaching an institution of higher education can no longer be considered a university.

Outsourcing Responsibility

With students showing up every year and with an obligation to provide services to them, one might imagine that an institution might take the opportunity to innovate and to evaluate ways in which it might stand out amongst the competition, truly looking after the group of people that in today’s increasingly commercialised education sector are considered the institution’s “customers”. When I was studying for my degree, the university’s mathematics department was in the process of developing computer-aided learning software for mathematics, which was regarded as a useful way of helping students improve their understanding of the course material through the application of knowledge recently acquired. However, such attempts to improve teaching quality are only likely to get substantial funding either through teaching-related programmes or by claiming some research benefit in the field of teaching or in another field. Consequently, developing software to benefit teaching is likely to be an activity located near the back of the queue for attention in a university, especially amongst universities whose leadership regard research commercialisation as their top priority.

So it becomes tempting for universities to minimise costs around student provision. Students are not meant to be sophisticated users whose demands must be met, mostly because they are not supposed to be around for long enough to be comfortable and for those providing services to eventually have to give in to student demands. Moreover, university employees are protected by workplace regulation (in theory, at least) whereas students are most likely protected by much weaker regulation. To take one example, whereas a university employee could probably demand appropriate accessibility measures for a disability they may have, students may have to work harder to get their disabilities recognised and their resulting needs addressed.

The Costs of Doing Business

So, with universities looking to minimise costs and to maximise revenue-generating opportunities, doing things like running infrastructure in a way that looks after the needs of the student and researcher populations seems like a distraction. University executives look to their counterparts in industry and see that outsourcing might offer a solution: why bother having people on the payroll when there are cloud computing services run by friendly corporations?

Let us take the most widely-deployed service, e-mail, as an example. Certainly, many students and employees might not be too concerned with logging into a cloud-based service to access their university e-mail – many may already be using such services for personal e-mail, and many may already be forwarding their university e-mail to their personal account – and although they might be irritated by the need to use one service when they have perhaps selected another for their personal use, a quick login, some adjustments to the mail forwarding settings, and logging out (never to return) might be the simple solution. The result: the institution supposedly saves money by making external organisations responsible for essential services, and the users get on with using those services in the ways they find most bearable, even if they barely take advantage of the specially designated services at all.

However, a few things may complicate this simplified scenario somewhat: reliability, interoperability, lock-in, and privacy. Reliability is perhaps the easiest to consider: if “Office 365” suddenly becomes “Office 360” for a few days, cloud-based services cannot be considered suitable for essential services, and if the “remedy” is to purchase infrastructure to bail out the cloud service provider, one has to question the decision to choose such an external provider in the first place. As for interoperability, if a user prefers Gmail, say, over some other hosted e-mail solution where that other solution doesn’t exchange messages properly with Gmail, that user will be in the awkward position of having to choose between a compromised experience in their preferred solution or an experience they regard as inconvenient or inferior. With services more exotic and less standardised than e-mail, the risk is that a user’s preferred services or software will not work with the chosen cloud-based service at all. Either way, users are forced to adopt services they dislike or otherwise have objections to using.

Product Placement

With users firmly parked on a specific vendor’s cloud-based platform, the temptation will naturally grow amongst some members of an organisation to “take advantage” of the other services on that platform whether they support interoperability or not. Users will be forced to log into the solution they would rather avoid or ignore in order to participate in processes and activities initiated by those who have actively embraced that platform. This is rather similar to the experience of getting a Microsoft Office document in an e-mail by someone requesting that one reads it and provides feedback, even though recipients may not have access to a compatible version of Microsoft Office or even run the software in question at all. In an organisational context, legitimate complaints about poor workflow, inappropriate tool use, and even plain unavailability of software (imagine being a software developer using a GNU/Linux or Unix workstation!) are often “steamrollered” by management and the worker is told to “deal with it”. Suddenly, everyone has to adapt to the tool choices of a few managerial product evangelists instead of participating in a standards-based infrastructure where the most important thing is just getting the work done.

We should not be surprised that vendors might be very enthusiastic to see organisations adopt both their traditional products as well as cloud-based platforms. Not only are the users exposed to such vendors’ products, often to the exclusion of any competing or alternative products, but by having to sign up for those vendors’ services, organisations are effectively recruiting customers for the vendor. Indeed, given the potential commercial benefits of recruiting new customers – in the academic context, that would be a new group of students every year – it is conceivable that vendors might offer discounts on products, waive the purchase prices, or even pay organisations in the form of services rendered to get access to new customers and increased revenue. Down the line, this pays off for the vendor: its organisational customers are truly locked in, cannot easily switch to other solutions, and end up paying through the nose to help the vendor recruit new customers.

How Much Are You Worth?

All of the above concerns are valid, but the most important one of all for many people is that of privacy. Now, most people have a complicated relationship with privacy: most people probably believe that they deserve to have a form of privacy, but at the same time many people are quite happy to be indiscreet if they think no-one else is watching or no-one else cares about what they are doing.

So, they are quite happy to share information about themselves (or content that they have created or acquired themselves) with a helpful provider of services on the Internet. After all, if that provider offers services that permit convenient ways of doing things that might be awkward to do otherwise, and especially if no money is changing hands, surely the meagre “payment” of tedious documents, mundane exchanges of messages, unremarkable images and videos, and so on, all with no apparently significant value or benefit to the provider, gets the customer a product worth far more in return. Everybody wins!

Well, there is always the matter of the small print – the terms of use, frequently verbose and convoluted – together with how other people perceive the status of all that content you’ve been sharing. As your content reaches others, some might perceive it as fair game for use in places you never could have imagined. Naturally, unintended use of images is no new phenomenon: I once saw one of my photographs being used in a school project (how I knew about it was that the student concerned had credited me, although they really should have asked me first, and an Internet search brought up their page in the results), whereas another photograph of mine was featured in a museum exhibition (where I was asked for permission, although the photograph was a lot less remarkable than the one found by the student).

One might argue that public sharing of images and other content is not really the same as sharing stuff over a closed channel like a social network, and so the possibility of unintended or undesirable use is diminished. But take another look at the terms of use: unlike just uploading a file to a Web site that you control, where nobody deems to claim any rights to what you are sharing, social networking and content sharing service providers frequently try and claim rights to your work.

Privacy on Parade

When everyone is seeking to use your content for their own goals, whether to promote their own businesses or to provide nice imagery to make their political advocacy more palatable, or indeed to support any number of potential and dubious endeavours that you may not agree with, it is understandable that you might want to be a bit more cautious about who wants a piece of your content and what they intend to do with it once they have it. Consequently, you might decide that you only want to deal with the companies and services you feel you can trust.

What does this have to do with students and the cloud? Well, unlike the services that a student may already be using when they arrive at university to start their studies, any services chosen by the institution will be imposed on the student, and they will be required to accept the terms of use of such services regardless of whether they agree with them or not. Now, although it might be said that the academic work of a student might be somewhat mundane and much the same as any other student’s work (even if this need not be the case), and that the nature of such work is firmly bound to the institution and it is therefore the institution’s place to decide how such work is used (even though this could be disputed), other aspects of that student’s activities and communications might be regarded as beyond the interests of the institution: who the student communicates with, what personal views they may express in such communications, what academic or professional views they may have.

One might claim that such trivia is of no interest to anyone, and certainly not to commercial entities who just want to sell advertising or gather demographic data or whatever supposedly harmless thing they might do with the mere usage of their services just to keep paying the bills and covering their overheads, but one should still be wary that information stored on some remote server in some distant country might somehow make its way to someone who might take a closer and not so benign interest in it. Indeed, the matter of the data residing in some environment beyond their control is enough for adopters of cloud computing to offer specially sanctioned exemptions and opt-outs. Maybe it is not so desirable that some foreign student writing about some controversial topic in their own country has their work floating around in the cloud, or as far as a university’s legal department is concerned, maybe it does not look so good if such information manages to wander into the wrong hands only for someone to ask the awkward question of why the information left the university’s own systems in the first place.

Excuses, Excuses

Cloud-based service providers are likely to respond to fears articulated about privacy violations and intrusions by insisting that such fears are disproportionate: that no-one is really looking at the data stored on their servers, that the data is encrypted somewhere/somehow, that if anything does look at the data it is merely an “algorithm” and not a person. Often these protests of innocence contradict each other, so that at any point in time there is at least one lie being told. But what if it is “only an algorithm” looking at your data? The algorithm will not be keeping its conclusions to itself.

How would you know what is really being done with your data? Not only is the code being run on a remote server, but with the most popular cloud services the important code is completely proprietary – service providers may claim to support Free Software and even contribute to it, but they do so only for part of their infrastructure – and you have no way of verifying any of their claims. Disturbingly, some companies want to enforce such practices within your home, too, so that when Microsoft claims that the camera on their most recent games console has to be active all the time but only for supposedly benign reasons and that the data is only studied by algorithms, the company will deny you the right to verify this for yourself. For all you know the image data could be uploaded somewhere, maybe only on command, and you would not only be none the wiser but you would also be denied the right to become wiser about the matter. And even if the images were not shared with mysterious servers, there are still unpleasant applications of “the algorithm”: it could, for example, count people’s faces and decide whether you were breaking the licensing conditions on a movie or other content by holding a “performance” that goes against the arbitrary licensing that accompanies a particular work.

Back in the world of the cloud, companies like Microsoft typically respond to criticism by pointing the finger at others. Through “shell” or “front” organisations the alleged faults of Microsoft’s competitors are brought to the attention of regulators, and in the case of the notorious FairSearch organisation, to take one example, the accusing finger is pointed at Google. We should all try and be aware of the misdeeds of corporations, that unscrupulous behaviour may have occurred, and we should insist that such behaviour be punished. But we should also not be distracted by the tactics of corporations that insist that all the problems reside elsewhere. “But Google!” is not a reason to stop scrutinising the record of a company shouting it out loud, nor is it an excuse for us to disregard any dubious behaviour previously committed by the company shouting it the loudest. (It is absurd that a company with a long history of being subject to scrutiny for anticompetitive practices – a recognised monopoly – should shout claims of monopoly so loudly, and it is even more absurd for anyone to take such claims at face value.)

We should be concerned about Google’s treatment of user privacy, but that should not diminish our concern about Microsoft’s treatment of user privacy. As it turns out, both companies – and several others – have some work to do to regain our trust.

I Do Not Agree

So why should students specifically be worried about all this? Does this not also apply to other groups, like anyone who is made to use software and services in their job? Certainly, this does affect more than just students, but students will probably be the first in line to be forced to accept these solutions or just not be able to take the courses they want at the institutions they want to attend. Even in countries with relatively large higher education sectors like the United Kingdom, it can be the case that certain courses are only available at a narrow selection of institutions, and if you consider a small country like Norway, it is entirely possible that some courses are only available at one institution. For students forced to choose a particular institution and to accept that institution’s own technological choices, the issue of their online privacy becomes urgent because such institutional changes are happening right now and the only way to work around them is to plan ahead and to make it immediately clear to those institutions that the abandonment of the online privacy rights (and other rights) of their “customers” is not acceptable.

Of course, none of this is much comfort to those working in private businesses whose technological choices are imposed on employees as a consequence of taking a job at such organisations. The only silver lining to this particular cloud is that the job market may offer more choices to job seekers – that they can try and identify responsible employers and that such alternatives exist in the first place – compared to students whose educational path may be constrained by course availability. Nevertheless, there exists a risk that both students and others may be confronted with having to accept undesirable conditions just to be able to get a study place or a job. It may be too disruptive to their lives not to “just live with it” and accept choices made on their behalf without their input.

But this brings up an interesting dilemma. Should a person be bound by terms of use and contracts where that person has been effectively coerced into accepting them? If their boss tells them that they have to have a Microsoft or Google account to view and edit some online document, and when they go to sign up they are presented with the usual terms that nobody can reasonably be expected to read, and given that they cannot reasonably refuse because their boss would then be annoyed at that person’s attitude (and may even be angry and threaten them with disciplinary action), can we not consider that when this person clicks on the “I agree” button it is only their employer who really agrees, and that this person not only does not necessarily agree but cannot be expected to agree, either?

Excuses from the Other Side

Recent events have probably made people wary of where their data goes and what happens with it once it has left their own computers, but merely being concerned and actually doing something are two different things. Individuals may feel helpless: all their friends use social networks and big name webmail services; withdrawing from the former means potential isolation, and withdrawing from the latter involves researching alternatives and trying to decide whether those alternatives can be trusted more than one of the big names. Certainly, those of us who develop and promote Free Software should be trying to provide trustworthy alternatives and giving less technologically-aware people the lifeline that they need to escape potentially exploitative services and yet maintain an active, social online experience. Not everyone is willing to sacrifice their privacy for shiny new online toys that supposedly need to rifle through your personal data to provide that shiny new online experience, nor is everyone likely to accept such constraints on their privacy when made aware of them. We should not merely assume that people do not care, would just accept such things, and thus do not need to be bothered with knowledge about such matters, either.

As we have already seen, individuals can make their own choices, but people in organisations are frequently denied such choices. This is where the excuses become more irrational and yet bring with them much more serious consequences. When an organisation chooses a solution from a vendor known to share sensitive information with other, potentially less friendly, parties, they might try and explain such reports away by claiming that such behaviour would never affect “business applications”, that such applications are completely separate from “consumer applications” (where surveillance is apparently acceptable, but no-one would openly admit to thinking this, of course), and that such a vendor would never jeopardise their relationship with customers because “as a customer we are important to them”.

But how do you know any of this? You cannot see what their online services are actually doing, who can access them secretly, whether people – unfriendly regimes, opportunistic law enforcement agencies, dishonest employees, privileged commercial partners of the vendor itself – actually do access your data, because how all that stuff is managed is secret and off-limits. You cannot easily inspect any software that such a vendor provides to you because it will be an inscrutable binary file, maybe even partially encrypted, and every attempt will have been made to forbid you from inspecting it both through licence agreements and legislation made at the request of exactly these vendors.

And how do you know that they value your business, that you are important to them? Is any business going to admit that no, they do not value your business, that you are just another trophy, that they share your private data with other entities? With documentation to the contrary exposing the lies necessary to preserve their reputation, how do you know you can believe anything they tell you at all?

The Betrayal

It is all very well for an individual to make poor decisions based on wilful ignorance, but when an organisation makes poor decisions and then imposes them on other people for those people to suffer, this ignorance becomes negligence at the very least. In a university or other higher education institution, apparently at the bottom of the list of people to consult about anything, the bottoms on seats, the places to be filled, are the students: the first in line for whatever experiment or strategic misadventure is coming down the pipe of organisational reform, rationalisation, harmonisation, and all the other buzzwords that look great on the big screen in the boardroom.

Let us be clear: there is nothing inherently wrong with storing content on some network-accessible service, provided that the conditions under which that content is stored and accessed uphold the levels of control and privacy that we as the owners of that data demand, and where those we have elected to provide such services to us deserve our trust precisely by behaving in a trustworthy fashion. We may indeed select a service provider or vendor who respects us, rather than one whose terms and conditions are unfathomable and who treats its users and their data as commodities to be traded for profits and favours. It is this latter class of service providers and vendors – ones who have virtually pioneered the corrupted notion of the consumer cloud, with every user action recorded, tracked and analysed – that this article focuses on.

Students should very much beware of being sent into the cloud: they have little influence and make for a convenient group of experimental subjects, with few powerful allies to defend their rights. That does not mean that everyone else can feel secure, shielded by employee representatives, trade unions, industry organisations, politicians, and so on. Every group pushed into the cloud builds the pressure on every subsequent group until your own particular group is pressured, belittled and finally coerced into resignation. Maybe you might want to look into what your organisation is planning to do, to insist on privacy-preserving infrastructure, and to advocate Free Software as the only effective way of building that infrastructure.

And beware of the excuses – for the favourite vendor’s past behaviour, for the convenience of the cloud, for the improbability that any undesirable stuff could happen – because after the excuses, the belittlement of the opposition, comes the betrayal: the betrayal of sustainable and decentralised solutions, the betrayal of the development of local and institutional expertise, the betrayal of choice and real competition, and the betrayal of your right to privacy online.

Norwegian Voting and the Illusion of “Open Source”

June 30th, 2013