Paul Boddie's Free Software-related blog

Paul's activities and perspectives around Free Software

Python 3: I Told You So?

January 4th, 2014

Five or so years ago I managed to achieve a small amount of notoriety by being quoted in a Linux.com article about Python 3 where I stated that Python 3 was all very well, but the efforts of the core development community would have been better spent on fixing the major perceived flaws with Python, specifically those affecting the “reference implementation” known as CPython that were giving Python a bad name. Now, in an article discussing the current state of Python 3 adoption, Alex Gaynor has belatedly arrived at the same conclusion. What is also interesting, however, is the response to his remarks about bridging the compatibility gap between Python 2 and Python 3.

Some people evidently seem to think that Python’s “benevolent dictator for life” Guido van Rossum should try harder to coerce people to use Python 3 instead of Python 2. Back in 2008, I pointed out what was rather obvious from the very start of the introduction of Python 3: it represents a considerable inconvenience for relatively little reward; people effectively need to put in lots of work just to arrive at what they already have with their Python 2 systems, albeit with some kind of future-proofing as a bonus (and even then, Python 3 has had its own share of compatibility discontinuities and false starts).

When people choose to adopt Free Software technologies, which is what most Python implementations are and what Python the language effectively is, they tend to want more control over those technologies, their roadmaps, and the pace at which they need to update and migrate their systems to benefit from the continued development of those technologies. Indeed, people resent being told to do thankless work at the command of other people, since in many cases this is precisely why they have abandoned or rejected proprietary software whose vendors have acted in such a dictatorial fashion towards their users and customers. And coercion can never really work in a viable Free Software community, anyway: as some people have pointed out, if the majority reject the direction of the project, they will happily see the leaders of the project recede into the distance leading a minority group that may even be diminishing, which is arguably what has happened here.

Free Software project leaders and developers have to remember that even if they have an abundance of time, energy and resources to bring to a project, the people who use and depend on that project’s software may not be able to match such investments themselves. Stamping one’s foot at the indifference of a community to adapt to exciting new ways of doing things shows a disregard for the investments the members of that community have already made in the project, and it demonstrates an arrogance which suggests that the supposed needs of the project surpass any and all needs of the project’s users, even when those of the project may be frivolous whereas those of its users may actually determine the continued viability of those users’ businesses or operations.

Opening Up the Road Ahead

When Python core developers by their own admission often do not use Python 3 as their primary platform, members of the wider community should hardly feel bad about sticking to Python 2. Pushing others in front to suffer the trials of migration is just one of the unfortunate traits exhibited by the whole Python 3 affair. The other one that comes to mind is the pandering to people who insisted that breaking backwards compatibility was essential to making Python a better language for their particular domain. I am reminded of various delegations of Lisp users supposedly entertaining a switch to Python (as their own language languishes in popularity) who insisted that certain improvements be made to make Python a worthy enough candidate for their use. Such people are best ignored for the most part (after taking on board any genuinely useful suggestions) because they never tend to stick around, anyway, and if they really are serious to adopt a technology then they will eventually make the effort to migrate all by themselves.

Certainly, one should never inconvenience the existing community to pander to a bunch of fickle potential users. And one should always lead by example, demonstrate the viability of the project’s direction, and show that as the project leadership one is willing to share the resulting inconvenience and thereby seek to reduce it for others through hard-won experience with the problems one is advocating that others should choose to face. Back in 2008, only a small part of my response to the author of the Linux.com article was quoted, but I originally wrote the following:

There is this argument, especially with open source projects but it applies more generally, that no-one is forced to adopt backward incompatible change, yet by indicating that the favoured version of the future is a backward incompatible one, people are confronted with what could be called a roadblock on their roadmap. Who will be responsible for maintenance of the language system if they choose not to take the favoured path? If any security fixes are required in the future, where will they come from?

I sincerely hope that the Python core developers do not continue to impose this roadblock on the community in the hope that people will be encouraged through such coercion to adopt Python 3. Yet it appears that hopes are still high that GNU/Linux distributions will still be able to switch to Python 3 and deprecate Python 2 in the relatively near future, provoked by a refusal of the core developers to continue to support Python 2 (either by maintaining the CPython implementation of it or by acknowledging it as the more widespread form of the language) and an apparent reluctance to allow others to do so under the Python community umbrella.

People will continue to use Python 2 for some time to come, and if they might one day consider switching to Python 3 it will only happen if they have not already been alienated by seemingly petty acts of the Python core developers who have sought to punish them for not enthusiastically embracing the project’s latest vision by some arbitrary deadline. Because, as has also been noted, it may be easier for those users to take another path and thus choose another technology entirely than to deal with this needless obstruction on the road ahead. And then, not even the reluctant embrace of actively maintained Python 2 implementations such as PyPy by the core developers will be able to mend the damage.

Integrating setup-kolab with Debian Packaging

December 18th, 2013

My recent diversion via pykolab may appear to have rather little to do with the matter of improving the Debian packaging situation for Kolab, but after initial tidying exercises with the pykolab code, I started to consider how the setup-kolab program should behave in the context of Debian packaging operations: what it should do when a package is installed, if anything, and whether it can rely on anything having been configured in advance. Until now, setup-kolab has been regarded as a tool that is run once the Kolab software is mostly or completely present on a system, but this is a somewhat different approach to the way many service-providing Debian packages are set up.

Take MySQL as an example. Upon installing the appropriate Debian package providing the MySQL server, the user is prompted to set up the administrative credentials for the server. After this brief interaction, MySQL should be available for general use without further configuration work, although it may be the case that some tuning might be beneficial. It seems to me that Kolab could be delivered with the same convenience in Debian.

The Different Ways of Configuring Kolab

Until now, many of the individual Kolab meta-packages – those grouping together individual components as functional units providing mail transport (MTA), storage (IMAP) or directory (LDAP) functionality – have only indirectly relied on the presence of the kolab-conf package providing the setup-kolab program. Indeed, if the top-level kolab meta-package is installed, kolab-conf will be pulled in as a dependency and setup-kolab will be available, and as noted above, since setup-kolab has been the program that configures a complete system, this makes some sense. However, this causes the work of configuring Kolab to be put off until the very end and thus to pile up so that a user may have to undertake a lengthy question-and-answer process to get the software working, and this can lead to mistakes and a non-working installation.

But setup-kolab is familiar with the notion of configuring individual components. Although the Kolab documentation has emphasised a “one shot” configuration of everything at once, setup-kolab can be asked to configure different individual things, such as the LDAP integration or the integration with Roundcube (the webmail software supported by Kolab). Thus, it becomes interesting to consider whether individual packages can be configured one by one using setup-kolab until they have all been configured, and whether this produces the same desired result of everything having been set up (and hopefully without the same intensity of questioning).

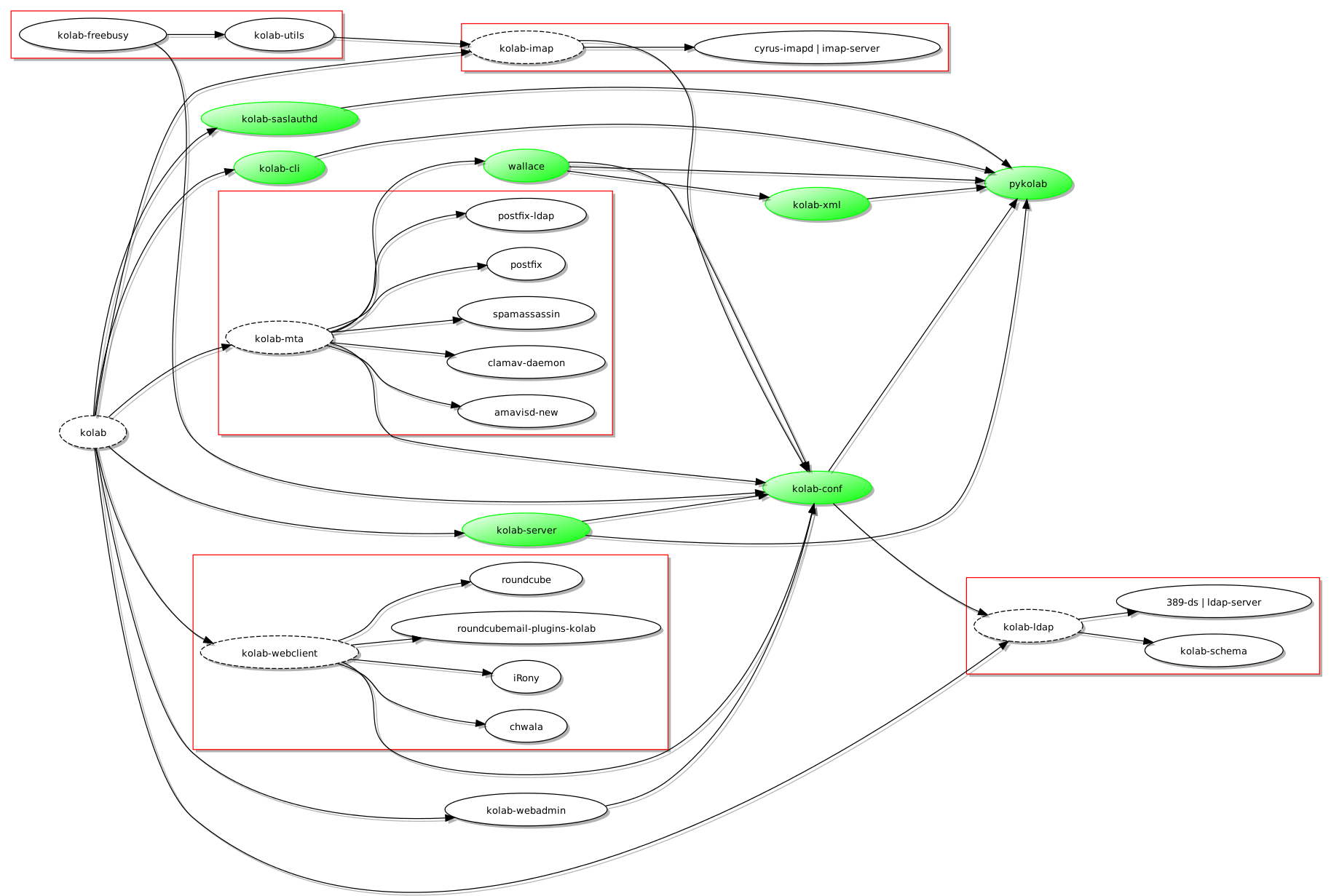

To make setup-kolab available to packages during their configuration, the kolab-conf package providing the program must be a dependency of each of the packages concerned. Here is a nice little diagram illustrating the result of a few adjustments to the dependency graph:

A revised dependency graph for Kolab (produced using Graphviz and tidied up using a modified version of vidarh's notugly.xsl stylesheet)

(Here, the pykolab packages are coloured in green and have been allowed to float freely to make the layout cleaner: pykolab contributes in a number of ways and the introduction of kolab-conf as a dependency of a few packages means that it is very much “in demand” by all parts of the graph.)

Now, with kolab-conf available when, for example, kolab-imap is being installed, the post-installation script of kolab-imap will be able to invoke setup-kolab and to make sure that a usable configuration is available by the time the Debian packaging system is done with the installation activity. But one thing might be bothering the attentive reader: why is kolab-ldap not dependent on kolab-conf? In fact, the configuration process has to start somewhere, and since information related to the LDAP directory is rather central to further configuration, this initial configuration takes place when the kolab-conf package is itself installed. And since this initial configuration needs access to the LDAP system, the dependency relationship is “inverted” for this single case, and kolab-conf populates the basic configuration so that subsequent package configuration can take advantage of this initial work.

Communicating with the User

Command line usage of setup-kolab involves some fairly straightforward console-style prompting and input, but during Debian packaging activities, it is widely regarded as a bad thing to have packaging scripts just ask for things from standard input and just write out messages to standard output or standard error: people may be using graphical package management tools that offer alternative facilities for user interaction, and it is possible that console-style operations go completely unnoticed by both the user and such tools. Thus, there is a need to make setup-kolab aware of the facility known as debconf (which is not to be confused with the DebConf series of conferences that may well appear in any searches made to try and discover documentation about the debconf system).

It would appear that debconf is used primarily within shell scripts, as the packaging scripts most commonly use the shell command language, but a goal of this work is surely to avoid replicating the activities of setup-kolab in other programs: it is not particularly desirable to have to rewrite the component-specific parts of pykolab in shell command language just to be able to use debconf to talk to users. Fortunately, the debconf package provides a Python wrapper for the debconf system, and although the documentation and examples are not particularly substantial or enlightening, a bit of experimentation and some consultation of the debconf specification has led to a workable level of interaction between setup-kolab and debconf so that the latter can prompt the user and supply the user’s input to the former without too much complaint.

What Next?

As previously stated, the aim now is to try and get the pykolab changes upstream – regardless of the Debian-related modifications, pykolab has been enhanced in other ways – and to try and reach consensus about whether this way of structuring the Debian dependencies is sensible or not. A substantial number of iterations involving pykolab adjustments, packaging improvements, pbuilder sessions and eventual deployment of the new packages in a virtual machine seem to indicate that the approach is not completely impractical, but it is possible that there are better ways of doing some of this work.

But certainly, my confidence in the Debian packaging situation for Kolab is significantly higher than it was before. I can now see a time when the matter of installing and configuring Kolab (at least for common deployment situations) will be seen as entirely uninteresting and a largely solved problem. Then, people will be able to concentrate on more interesting matters instead.

Adventures in Kolab Packaging and pykolab

December 13th, 2013

After my previous efforts at building Kolab packages using more traditional Debian methods, my attention then turned to the nature of the software itself, particularly since the Debian Kolab packages (as currently available from the Kolab project’s own repository) do not configure the software so that it is immediately usable: that job is assigned to a program called setup-kolab, which is provided in the kolab-conf Debian package but really lives in the pykolab software distribution. Thus, my focus shifted to what pykolab is and does, and to any ways I might be able to improve or adjust that software.

A quick examination of the Debian packages produced by the pykolab source package gives an indication of the different things pykolab provides: a command framework for configuration (kolab-conf), a command framework for administration (kolab-cli), and an underlying library that supports these and other packages (pykolab). It surprised me slightly that there was so much Python involved with Kolab – my perception had been that the project was mostly KDE-related C++ libraries combined with PHP Web applications (sitting on top of some fairly well-known and established programs and libraries) – and since my primary programming language has been Python for quite some time, I took the opportunity to go through the code and see if there were any trivial but worthwhile adjustments that could be made to make more substantial further improvements more convenient.

Upon emerging from some verbose tidying efforts, hopefully being merged into the upstream code in the near future, I turned my attention to the way setup-kolab behaves. Although the tool mostly does the job already, there are things about it that are perhaps not quite as convenient as they could be. For example, until now, setup-kolab has made the user specify database credentials to access the MySQL database system (unless an explicit component other than MySQL or Roundcube has been indicated as an argument to the program), and in many cases this is not really necessary: the required database may already exist, and on a Debian system there are established ways to query the database system about existing databases without asking the user for the login details. Another desirable feature is that of being able to run setup-kolab and not have it try and perform configuration tasks that have already been done: although prior LDAP directory instances are detected and setup-kolab refuses to go any further unless a special option is given as a command argument, it would be nice if setup-kolab just mentioned that no work needs to be done, at least for most of the components.

Ultimately, setup-kolab might itself be called from packaging scripts invoked during the installation of various different packages, perhaps bringing in the debconf framework to present a standardised interface on Debian systems, but hopefully not demanding the user’s attention at all. Until then, I hope that it can offer a convenient way of setting Kolab up and/or checking that the different components are ready to support Kolab in use.

More Fun with Packaging

Changing the actual pykolab source code did also involve building the different binary packages from the pykolab source package, but this meant that doing other packaging-related things was largely ignored until someone asked a question on the #kolab IRC channel about the free/busy component and how it should be configured to function. I had not looked very much at this component at all, and I discovered that I did not even have it installed. The kolab-freebusy package sits on top of the other Kolab-related packages, so as I had been installing the kolab package and watching various dependencies being pulled in, kolab-freebusy managed to avoid being installed. (This is understandable from a packaging perspective as the free/busy functionality is an extension to the basic services provided by Kolab.)

Upon inspecting the configuration of the kolab-freebusy package, I noticed that it had not been set up right, either in its default configuration or by setup-kolab. Some further investigation revealed that setup-kolab was trying to configure a file that the kolab-freebusy package had renamed, thus making configuration somewhat ineffective. Fortunately, although not without some duplicated work before I realised, this particular bug had already been fixed in a later version of the package. Still, one or two other things also needed changing and thus a trip via pbuilder was in order.

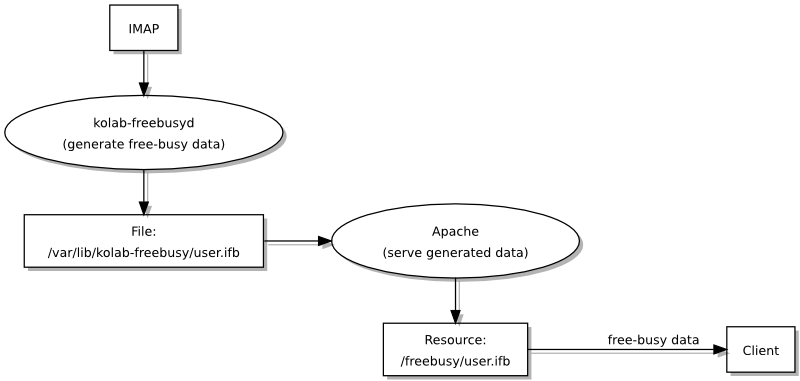

One of the things that needed changing, or at least refining, concerns the relationship between kolab-freebusy and kolab-utils. The latter package provides the “free/busy daemon”, and one may indeed wonder what this is when the free/busy functionality must surely be provided by the package with the more obvious name. In fact, this is where a picture can be very descriptive:

The basic free/busy architecture in Kolab (made with Graphviz and made nicer using vidarh's notugly.xsl template)

So, since Kolab stores calendar information in IMAP but wants to be able to publish it in a relatively efficient way, the daemon runs periodically and exports free/busy resources for calendar users. Such information is then provided upon request when clients access the free/busy Web service provided by the kolab-freebusy package.

Although one can install only the Web service (in the kolab-freebusy package) and ask for free/busy information, the exercise is rather pointless: there will be no information to retrieve, at least in the default configuration of the system and with the default functionality being offered; only after obtaining and running the daemon (in the kolab-utils package) will the Web service have any use. I am inclined to think that if someone wants to install and use kolab-freebusy, they should also have kolab-utils pulled in for their convenience (or perhaps a package that only provides the daemon).

In Conclusion

All in all, I think Kolab offers plenty of things to explore, review, and – on occasion – fix or improve, but it has to be mentioned that once the packages provided the right directories for logging and free/busy resource storage, and once the Web service started to use the correct configuration, everything seemed to work as intended. I hope that with some more polishing, we will see something that more people will be able to try out and perhaps feel comfortable using in their own organisation.

Some things I would like to see, as I noted on the mailing list, include…

- Getting some of my changes upstream and into the packaging. On the latter front, the Kolab packaging effort in Debian itself is apparently being revived: this will be highly beneficial in a number of ways, not least that of using Debian-native packaging tools instead of the less-than-optimal Open Build Service.

- A revival of the Kolab Wiki. It is nice to be able to write things up somewhere, evolve a consensus about how things might be done, and collaboratively describe how things are already done: it is rather hard to do this on mailing lists or using reference documentation tools like Sphinx, and blogging about it only achieves so much.

- Actually improving the functionality and not just the nuts and bolts of getting Kolab installed and set up.

Obviously, I aim to continue doing these things and not just ask for things and expect to see others doing them, and I am quite sure that there are others in the community who are similarly motivated. If your organisation could benefit from Kolab or does so already, or if it benefits from any Free Software groupware solution, please consider supporting the developers of those solutions in their work.

Without actively developed Free Software groupware, there is a risk that, over time, other Free Software deployed in the average organisation may be under threat as proprietary software vendors and uninformed decision-makers use excuse after excuse to flush out diversity and replace it with their own favourite monoculture of proprietary products and solutions. By supporting Free Software groupware and establishing basic infrastructure founded on Free Software and open standards in your own organisation, you establish an environment of fair competition, nurture a healthy and often necessary technological diversity, and you give your organisation the strategic freedom that would otherwise be denied to you.

To have the choice of Free Software in any particular application or field, we need to sustain those giving us that choice and not just say that we would use it “if only it were better” and then pay a proprietary vendor for something nicer or shinier instead. Please keep such things in mind when evaluating solutions for your organisation’s immediate and future needs.

Neo900: Turning the corner

December 2nd, 2013

Back when I last wrote about the status of the Neo900 initiative, the fundraising had just begun and the target was a relatively modest €25000 by “crowdfunding” standards. That target was soon reached, but it was only ever the initial target: the sum of money required to prototype the device and to demonstrate that the device really could be made and could eventually be sold to interested customers. Thus, to communicate the further objectives of the project, the Neo900 site updated their funding status bar to show further funding objectives that go beyond mere demonstrations of feasibility and that also cover different levels of production.

So what happened here? Well, one of the slightly confusing things was that even though people were donating towards the project’s goals, it was not really possible to consider all of them as potential customers, so if 200 people had donated something (anything from, say, €10 right up to €5000), one could not really rely on them all coming back later to buy a finished device. People committing €100 or more might be considered as a likely purchaser, especially since donations of that size are effectively treated as pledges to buy and qualify for a rebate on a finished device, but people donating less might just be doing so to support the project. Indeed, people donating €100 or more might also only be doing so to support the project, but it is probably reasonable to expect that the more people have given, the more likely they are to want to buy something in the end. And, of course, if someone donates the entire likely cost of a device, a purchase has effectively been made already.

So even though the initiative was able to gauge a certain level of interest, it was not able to do so precisely purely by considering the amount of financial support it had been receiving. Consequently, by measuring donations of €100 or more, a more realistic impression of the scale of eventual production could be obtained. As most people are aware, producing things in sufficient quantity may be the only way that a product can get made: setup costs, minimum orders of components, and other factors mean that small runs of production are prohibitively expensive. With 200 effective pledges to buy, the initiative can move beyond the prototyping phase and at least consider the production phase – when they are ready, of course – without worrying too much that there will be a lack of customers.

Since my last report, media coverage has even extended into the technology mainstream, with Wired even doing a news article about it. Meanwhile, the project itself demonstrated mechanically compatible hardware and the modem hardware they intend to use, also summarising component availability and potential problems with the sourcing of certain components. For the most part, things are looking good indeed, with perhaps the only cloud on the horizon being a component with a 1000-unit minimum order quantity. That is why the project will not be stopping with 200 potential customers: the more people that jump on board, the greater the chances that everyone will be able to get a better configuration for the device.

If this were a mainstream “crowdfunding” effort, they might call that a “stretch goal”, but it is really a consequence of the way manufacturing is done these days, giving us economies of scale on the one hand, but raising the threshold for new entrants and independent efforts on the other. Perhaps we will eventually see innovations in small-scale manufacturing, not just in the widely-hyped 3D printing field, but for everything from electronic circuits to screens and cases, that may help eliminate some of the huge fixed costs and make it possible to design and make complicated devices relatively cheaply.

It will certainly be interesting to see how many more people choose to extend the lifespan of their N900 by signing up, or how many embrace the kind of smartphone that the “fickle market” supposedly does not want any more. Maybe as more people join in, more will be encouraged to join in as well, and so some kind of snowball effect might occur. Certainly, with the transparency shown in the project so far, people will at least be able to make an informed decision about whether they join in or not. And hopefully, we will eventually see some satisfied customers with open hardware running Free Software, good to go for another few years, emphasizing once again that the combination is an essential ingredient in a sustainable technological society.

The Organisational Panic Button and the Magic Single Vendor Delusion

November 27th, 2013

I have had reason to consider the way organisations make technology choices in recent months, particularly where the public sector is concerned, and although my conclusions may not come as a surprise to some people, I think they sum up fairly well how bad decisions get made even if the intentions behind them are supposedly good ones. Approaching such matters from a technological point of view, being informed about things like interoperability, systems diversity, the way people adopt and use technology, and the details of how various technologies work, it can be easy to forget that decisions around acquisitions and strategies are often taken by people who have no appreciation of such things and no time or inclination to consider them either: as far as decision makers are concerned, such things are mere details that obscure the dramatic solution that shows them off as dynamic leaders getting things done.

Assuming the Position

So, assume for a moment that you are a decision-maker with decisions to make about technology, that you have in your organisation some problems that may or may not have technology as their root cause, and that because you claim to listen to what people in your organisation have to say about their workplace, you feel that clear and decisive measures are required to solve some of those problems. First of all, it is important to make sure that when people complain about something, they are not mixing that thing up with something else that really makes their life awkward, but let us assume that you and your advisers are aware of that issue and are good at getting to the heart of the real problem, whatever that may be. Next, people may ask for all sorts of things that they want but do not actually need – “an iPad in every meeting room, elevator and lavatory cubicle!” – and even if you also like the sound of such wild ideas, you also need to be able to restrain yourself and to acknowledge that it would simply be imprudent to indulge every whim of the workforce (or your own). After all, neither they nor you are royalty!

With distractions out of the way, you can now focus on the real problems. But remember: as an executive with no time for detail, the nuances of a supposedly technological problem – things like why people really struggle with some task in their workplace and what technical issues might be contributing to this discomfort – these things are distractions, too. As someone who has to decide a lot of things, you want short and simple summaries and to give short and simple remedies, delegating to other people to flesh out the details and to make things happen. People might try and get you to understand the detail, but you can always delegate the task of entertaining such explanations and representations to other people, naturally telling them not to waste too much time on executing the plan.

On the Wrong Foot

So, let us just consider what we now know (or at least suspect) about the behaviour of someone in an executive position who has an organisation-wide problem to solve. They need to demonstrate leadership, vision and intent, certainly: it is worth remembering that such positions are inherently political, and if there is anything we should all know about politics by now, it is that it is often far more attractive to make one’s mark, define one’s legacy, fulfil one’s vision, reserve one’s place in the history books than it is to just keep things running efficiently and smoothly and to keep people generally satisfied with their lot in life; this principle alone explains why the city of Oslo is so infatuated with prestige projects and wants to host the Winter Olympics in a few years’ time (presumably things like functioning public transport, education, healthcare, even an electoral process that does not almost deliberately disenfranchise entire groups of voters, will all be faultless by then). It is far more exciting being a politician if you can continually announce exciting things, leaving the non-visionary stuff to your staff.

Executives also like to keep things as uncluttered as possible, even if the very nature of a problem is complicated, and at their level in the organisation they want the explanations and the directives to be as simple as possible. Again, this probably explains the “rip it up and start over” mentality that one sees in government, especially after changes in government even if consecutive governments have ideological similarities: it is far better to be seen to be different and bold than to be associated with your discredited predecessors.

But what do these traits lead to? Well, let us return to an organisational problem with complicated technical underpinnings. Naturally, decision-makers at the highest levels will not want to be bored with the complications – at the classic “10000 foot” view, nothing should be allowed to encroach on the elegant clarity of the decision – and even the consideration of those complications may be discouraged amongst those tasked to implement the solution. Such complications may be regarded as a legacy of an untidy and unruly past that was not properly governed or supervised (and are thus mere symptoms of an underlying malaise that must be dealt with), and the need to consider them may draw time and resources away from an “urgently needed” solution that deals with the issue no matter what it takes.

How many times have we been told “not to spend too much time” on something? And yet, that thing may need to be treated thoroughly so that it does not recur over and over again. And as too many people have come to realise or experience, blame very often travels through delegation: people given a task to see through are often deprived of resources to do it adequately, but this will not shield them from recriminations and reprisals afterwards.

It should not demand too much imagination to realise that certain important things will be sacrificed or ignored within such a decision-making framework. Executives will seek simplistic solutions that almost favour an ignorance of the actual problem at hand. Meanwhile, the minions or underlings doing the work may seek to stay as close as possible to the exact word of the directive handed down to them from on high, abandoning any objective assessment of the problem domain, so as to be able to say if or when things go wrong that they were only following the instructions given to them, and that as everything falls to pieces it was the very nature of the vision that led to its demise rather than the work they did, or that they took the initiative to do something “unsanctioned” themselves.

The Magic Single Vendor Temptation

We can already see that an appreciation of the finer points of a problem will be an early casualty in the flawed framework described above, but when pressure also exists to “just do something” and when possible tendencies to “make one’s mark” lie just below the surface, decision-makers also do things like ignore the best advice available to them, choosing instead to just go over the heads of the people they employ to have opinions about matters of technology. Such antics are not uncommon: there must be thousands or even millions of people with the experience of seeing consultants breeze into their workplace and impart opinions about the work being done that are supposedly more accurate, insightful and valuable than the actual experiences of the people paid to do that very work. But sometimes hubris can get the better of the decision-maker to the extent that their own experiences are somehow more valid than those supposed experts on the payroll who cannot seem to make up their minds about something as mundane as which technology to use.

And so, the executive may be tempted to take a page from their own playbook: maybe they used a product in one of their previous organisations that had something to do with the problem area; maybe they know someone in their peer group who has an opinion on the topic; maybe they can also show that they “know about these things” by choosing such a product. And with so many areas of life now effectively remedied by going and buying a product that instantly eradicates any deficiency, need, shortcoming or desire, why would this not work for some organisational problem? “What do you mean ‘network provisioning problems’? I can get the Internet on my phone! Just tell everybody to do that!”

When the tendency to avoid complexity meets the apparent simplicity of consumerism (and of solutions encountered in their final form in the executive’s previous endeavours), the temptation to solve a problem at a single stroke or a single click of the “buy” button becomes great indeed. So what if everyone affected by the decision has different needs? The product will surely meet all those needs: the vendor will make sure of that. And if the vendor cannot deliver, then perhaps those people should reconsider their needs. “I’ve seen this product work perfectly elsewhere. Why do you people have to be so awkward?” After all, the vendor can work magic: the salespeople practically told us so!

Nothing wrong here: a public transport "real time" system failure; all the trains are arriving "now"

The Threat to Diversity

In those courses in my computer science degree that dealt with the implementation of solutions at the organisational level, as opposed to the actual implementation of software, attempts were made to impress upon us students the need to consider the requirements of any given problem domain because any solution that neglects the realities of the problem domain will struggle with acceptance and flirt with failure. Thus, the impatient executive approach involving the single vendor and their magic product that “does it all” and “solves the problem” flirts openly and readily with failure.

Technological diversity within an organisation frequently exists for good reason, not to irritate decision-makers and their helpers, and the larger the organisation the larger the potential diversity to be found. Extrapolating from narrow experiences – insisting that a solution must be good enough for everyone because “it is good enough for my people” – risks neglecting the needs of large sections of an organisation and denying the benefits of diversity within the organisation. In turn, this risks the health of those parts of an organisation whose needs have now been ignored.

But diversity goes beyond what people happen to be using to do their job right now. By maintaining the basis for diversity within an organisation, it remains possible to retain the freedom for people to choose the most appropriate systems and platforms for their work. Conversely, undermining diversity by imposing a single vendor solution on everyone, especially when such solutions also neglect open standards and interoperability, threatens the ability for people to make choices central to their own work, and thus threatens the vitality of that work itself.

Stories abound of people in technical disciplines who “also had to have a Windows computer” to do administrative chores like fill out their expenses, hours, travel claims, and all the peripheral tasks in a workplace, even though they used a functioning workstation or other computer that would have been adequate to perform the same chores within a framework that might actually have upheld interoperability and choice. Who pays for all these extra computers, and who benefits from such redundancy? And when some bright spark in the administration suggests throwing away the “special” workstation, putting administrative chores above the real work, what damage does this do to the working environment, to productivity, and to the capabilities of the organisation?

Moreover, the threat to diversity is more serious than many people presumably understand. Any single vendor solution imposed across an organisation also threatens the independence of the institution when that solution also informs and dictates the terms under which other solutions are acquired and introduced. Any decision-maker who regards their “one product for everybody” solution as adequate in one area may find themselves supporting a “one vendor for everything” policy that infects every aspect of the organisation’s existence, especially if they are deluded enough to think that they getting a “good deal” by buying all their things from that one vendor and thus unquestioningly going along with it all for “economic reasons”. At that point, one has to wonder whether the organisation itself is in control of its own acquisitions, systems or strategies any longer.

Somebody Else’s Problem

People may find it hard to get worked up about the tools and systems their employer uses. Surely, they think, what people have chosen to run a part of the organisation is a matter only for those who work with that specific thing from one day to the next. When other people complain about such matters, it is easy to marginalise them and to accuse them of making trouble for the sake of doing so. But such reactions are short-sighted: when other people’s tools are being torn out and replaced by something less than desirable, bystanders may not feel any urgency to react or even think about showing any sympathy at all, but when tendencies exist to tackle other parts of an organisation with simplistic rationalisation exercises, who knows whose tools might be the next ones to be tampered with?

And from what we know from unfriendly solutions that shun interoperability and that prefer other solutions from the same vendor (or that vendor’s special partners), when one person’s tool or system gets the single vendor treatment, it is not necessarily only that person who will be affected: suddenly, other people who need to exchange information with that person may find themselves having to “upgrade” to a different set of tools that are now required for them just to be able to continue that exchange. One person’s loss of control may mean that many people lose control of their working environment, too. The domino effect that follows may result in an organisation transformed for the worse based only on the uninformed gut instincts of someone with the power to demand that something be done the apparently easy way.

Inconvenience: a crane operating over one pavement while sitting on the other, with a sign reading "please use the pavement on the other side"

Getting the Message Across

For those of us who want to see Free Software and open standards in organisations, the dangers of the top-down single vendor strategy are obvious, but other people may find it difficult to relate to the issues. There are, however, analogies that can be illustrative, and as I perused a publication related to my former employer I came across an interesting complaint that happens to nicely complement an analogy I had been considering for a while. The complaint in question is about some supplier management software that insists that bank account numbers can only have 18 digits at most, but this fails to consider the situation where payments to Russian and Chinese accounts might need account numbers with more than 18 digits, and the complainant vents his frustration at “the new super-elite of decision makers” who have decided that they know better than the people actually doing the work.

If that “super-elite” were to call all the shots, their solution would surely involve making everyone get an account with an account number that could only ever have 18 digits. “Not supported by your bank? Change bank! Not supported in your country? Change your banking country!” They might not stop there, either: why not just insist on everyone having an account at just one organisation-mandated bank? “Who cares if you don’t want a customer relationship with another bank? You want to get paid, don’t you?”

At one former employer of mine, setting up a special account at a particular bank was actually how things were done, but ignoring peculiarities related to the nature of certain kinds of institutions, making everyone needlessly conform through some dubiously justified, executive-imposed initiative whether it be requiring them to have an account with the organisation’s bank, or requiring them to use only certain vendor-sanctioned software (and as a consequence requiring them to buy certain vendor-sanctioned products so that they may have a chance of using them at work or to interact with their workplace from home) is an imposition too far. Rationalisation is a powerful argument for shaking things up, but it is often used by those who do not care how much it manages to transfer the inconvenience in an organisation to the individual and to other parties.

Bearing the Costs

We have seen how the organisational cost of short-sighted, buy-and-forget decision-making can end up being borne by those whose interests have been ignored or marginalised “for the good of the organisation”, and we can see how this can very easily impose costs across the whole organisation, too. But another aspect of this way of deciding things can also be costly: in the hurry to demonstrate the banishment of an organisational problem with a flourish, incremental solutions that might have dealt with the problem more effectively can become as marginalised as the influence of the people tasked with the job of seeing any eventual solution through. When people are loudly demanding improvements and solutions, an equally dramatic response probably does not involve reviewing the existing infrastructure, identifying areas that can provide significant improvement without significant inconvenience or significant additional costs, and committing to improve the existing solutions quietly and effectively.

Thus, when faced with disillusionment – that people may have decided for themselves that whatever it was that they did not like is now beyond redemption – decision-makers are apt to pander to such disillusionment by replacing any existing thing with something completely new. Especially if it reinforces their own blinkered view of an organisational problem or “confirms” what they “already know”, decision-makers may gladly embrace such dramatic acts as a demonstration of the resolve expected of a decisive leader as they stand to look good by visibly banishing the source of disillusionment. But when such pandering neglects relatively inexpensive, incremental improvements and instead incurs significant costs and disruptions for the organisation, one can justifiably question the motivations behind such dramatic acts and the level of competence brought to bear on resolving the original source of discomfort.

Mission Accomplished?

Thinking that putting down money with a single vendor will solve everybody’s problems, purging diversity from an organisation and stipulating the uniformity encouraged by that vendor, is an overly simplistic and even deluded approach to organisational change. Change in any organisation can be very expensive and must therefore be managed carefully. Change for the sake of change is therefore incredibly irresponsible. And change imposed to gratify the perception of change or progress, made on a superficial basis and incurring unnecessary and avoidable burdens within an organisation whilst risking that organisation’s independence and viability, is nothing other than indefensible.

Be wary of the “single vendor fixes it all” delusion, especially if all the signs point to a decision made at the highest levels of your organisation: it is the sign of the organisational panic button being pressed while someone declares “Mission Accomplished!” Because at the same time they will be thinking “We will have progress whatever the cost!” And you, not them, will be the one bearing the cost.

Packaging Kolab for Debian using pbuilder

November 15th, 2013

My recent excursion into Debian packaging with Kolab has involved a tour of lots of different tools and services, but it started out with a brief attempt to build the existing packages with pbuilder: a tool that has become fairly familiar to me in the process of experimenting with Debian packages and even contributing one to “Debian proper”. After some initial frustrations that prevented me from building packages using my normal workflow, I decided to familiarise myself with the infrastructure that the Kolab project itself uses to make packages, if only to reassure myself that the packages really could be built and didn’t require any special magic to do so. I won’t go into this because Timotheus has already done so in sufficient depth.

After some playing around with osc and the Development project in the Kolab OBS (Open Build Service), building packages, installing them in Debian root filesystems and User Mode Linux instances (administered by some scripts I’ve developed over the years), I persuaded myself to have another go at feeding the packages to pbuilder via the pdebuild tool, determined to overcome any build issues and to demonstrate that it could be done. One fairly good reason for doing this is that even though pbuilder-based builds can be sluggish as pbuilder decides to unpack an existing filesystem, install build dependencies, and do other housekeeping before actually building the package, it seems to be more efficient and quicker than osc, which I found took as long as 9 minutes before it was ready to build a relatively straightforward Python-based package. Another reason for going with pbuilder is that it is what the Debian project itself will be using, more or less, if – hopefully when – the packages get accepted back into Debian, whereas the OBS infrastructure seems to be based on other technologies for the management of the build environment.

Packages of the Future

One challenge posed by Kolab is that some of its packages depend on some of the other Kolab-provided packages when being built – those other packages are so-called “build dependencies” – but tools like pdebuild rely on such build dependencies already being available as installable packages from the Debian archive. For things like make and gcc, this isn’t a problem at all: they were packaged a very long time ago (although I suppose you could get caught out with very recent versions of such packages). But when a yet-to-be-submitted package is required as a build dependency for another package, the issue of satisfying that dependency arises, and this was something I hadn’t encountered before.

A perusal of the Debian Wiki provided a solution: after building the packages that the other ones rely upon, put them in a directory, expose them in a repository, and then make pbuilder consult that repository when deciding how it can satisfy those build dependencies. This involves three things:

- A directory with newly built packages, obviously, together with the necessary package metadata.

- A hook script that will refresh the metadata and perform the necessary update action that lets the pbuilder environment know about the packages.

- A special configuration for pbuilder.

The Package Directory

At first, this will contain nothing at all, but as you add packages it will contain both .deb package files and the package metadata. We will call this directory deps.

The Hook Script

As the Debian Wiki page describes, a hook called D05deps can be placed in a directory called, say, hooks and populated with the following code:

#!/bin/sh (cd /path-to-kolab-packaging/deps; apt-ftparchive packages . > Packages) apt-get update

I did find that the permissions on the hook file were crucial, fixing them as follows:

chmod a+x hooks/D05deps

Otherwise, no mention of the script will be made in the copious output from pbuilder and it will simply be ignored. I also experienced some initial problems with the package metadata, but running the first line of actual commands from the script and manually producing the metadata was enough to get pbuilder on the right track:

cd deps; apt-ftparchive packages . > Packages

After that, it didn’t have any difficulties seeing the new packages as I added them to the deps directory.

The Configuration File

All this has to do is to point to the deps and hooks directories. You can more or less copy the contents of /etc/pbuilderrc and add the following to it (customising it for your own choices, of course):

OTHERMIRROR="deb [trusted=yes] file:///path-to-kolab-packaging/deps ./" BINDMOUNTS="/path-to-kolab-packaging/deps" HOOKDIR="/path-to-kolab-packaging/hooks" EXTRAPACKAGES="apt-utils"

Yes, there really isn’t anything different about this than the example on the Debian Wiki page. I put this configuration file alongside the deps and hooks directories and called it pbuilderrc.

Actually Building Packages

With the above extra stuff in place, the process of building packages is slightly different: you have to tell pbuilder to use this alternative configuration, and then you just hope that all the different aspects of it are consistent and that pbuilder is able to take notice of it. The command that will eventually be run inside a directory containing “Debianized” sources is the following:

pdebuild -- --distribution wheezy --override-config --configfile ../pbuilderrc

Obviously, the pbuilderrc file resides in the parent directory after you change into a package’s sources directory.

Build Order

Above, I mentioned that some packages depend on others in order to be built. Finding out which packages are affected involves consulting their build dependencies which are conveniently listed in their .dsc files. Doing the following permits a general overview to be obtained and the basis of a suitable build order to be worked out:

grep ^Build-Depends *.dsc

Obviously, it makes sense to start with packages that do not depend on others that are also being built for this exercise. Devising or discovering an automated approach for this is left as an exercise for the reader, but Kolab is relatively uncomplicated and I used the following build order:

python-icalendar pykolab libkolabxml libcalendaring libkolab kolab kolab-freebusy kolab-schema kolab-syncroton kolab-utils kolab-webadmin mozilla-ldap-sdk chwala irony pyasn1-modules php-http-request2 roundcubemail roundcubemail-plugin-contextmenu roundcubemail-plugin-dblog roundcubemail-plugin-threadingasdefault roundcubemail-plugins-kolab smarty3

The General Workflow

To obtain, unpack and build the packages I used the following workflow:

- Visit the package downloads page (found via the Development project’s repository overview) and obtain a list of package URLs.

- Get each package using dget from the devscripts package. This will probably give a warning about unsigned or unverifiable packages and not unpack the sources. (I suppose that importing the repository key using apt-key fixes this. One should obviously consider the risks and recommendations around downloading code from the Internet.)

- Unpack each package using dpkg-source. For example:

dpkg-source -x python-icalendar_3.4-1.dsc

- Change into the source directory.

- Run the pdebuild command given above.

- Copy or move the resulting package files from /var/cache/pbuilder/result into the deps directory.

- Optional but tidy: move the other artefacts of building from the parent directory into some other place for future reference.

There are probably much more efficient and cleaner ways of building lots of packages, but this allowed me to inspect them and to consider a few changes.

Making Changes

I took the opportunity to make some changes to the python-icalendar package because I saw that it wanted me to install python-setuptools before pdebuild would even launch pbuilder. I have little confidence in setuptools generally and would prefer not to have it on my system, and it is an unfortunate but recurring phenomenon that one finds the setup.py script commonly used for the preparation or installation of Python software packages using setuptools when its functionality only requires the older and less disruptive distutils library. Regardless of whether such changes are desired in the eventual Kolab packaging, I took the opportunity to investigate how changes should be made to the package.

Modern Debian packages prefer such “upstream patching” – where the code being changed originates with the actual developers of the software, as opposed to people packaging it for different distributions – to be done using a tool called quilt. I have some experience using quilt for my previous packaging work, but it’s easy to forget how to use it. Fortunately, the Debian Wiki came to the rescue once again. Here’s what I did in the sources directory for the package:

quilt new setup.py.patch # tell quilt about my patch quilt add setup.py # tell quilt that I will patch setup.py # Now, I edited setup.py to replace setuptools with distutils. quilt refresh # update the patch within quilt quilt pop -a # go back to the way everything was (but remember the patch for later)

When running pdebuild, the tool will notice such patches and apply them. Upon finishing they should be provided in a file containing all the necessary patches that allow the software to be built as a package. In this case, a file called python-icalendar_3.4-1.debian.tar.gz was produced.

One or two things are probably necessary to make this work:

- A suitable quilt configuration as described on the Debian Wiki page referenced above.

- A suitable debian/source/format file containing the 3.0 (quilt) value.

What Next?

Some of the previously encountered pitfalls had very little to do with the actual packaging of Kolab in terms of getting the software installed, but were more to do with the way it behaved once configured (and perhaps how the configuration gets done). I intend to look a bit more closely at the configuration process and to see if some of the awkward situations that may arise can’t be diagnosed and remedied by some helpful enhancements to the tools. On the way, I expect to find areas of improvement in the ways some things are done – that’s just the way things are with software – but with regard to the packaging itself most of the hard work has already been done and it seems to hold up rather well. So thanks are obviously due to Paul and Jeroen (and others) for allowing me to join in at this fairly late stage in the game.

Notions of Progress on the Free Software Desktop

November 7th, 2013

Once again, discussion about Free Software communities is somewhat derailed by reflections on the state of the Free Software desktop. To be fair to participants in the discussion, the original observations about communities were so unspecific that people would naturally wonder which communities were being referenced.

Usability and Accessibility

As always, frustrating elements of recent Free Software desktop environments were brought up for criticism and evaluation. One of them concerned the “plasmoid” enhancements of KDE 4 (or KDE Plasma Desktop as it is known according to the rebranding of KDE assets) which are often regarded as superfluous distractions from the work of perfecting the classic desktop environment. Amidst all this, the “folder view” plasmoid (or desktop widget) in particular came under scrutiny. As I understand it, the “folder view” is just a panel or window that groups icons in a region on the desktop background, and I acknowledged that it certainly represents an improvement over managing icons on a normal desktop, but that it can also confuse people when they accidentally close the folder view – easy to do with a stray mouse click – leaving them to wonder where their icons went.

Such matters of usability make me wonder how well tested some of the concepts employed in these environments really are, despite insistences that usability experts have been involved and that non-experts in the field of usability are unable to see the forest for the trees. From my own experiences, I feel that the developers would really benefit from doing phone support for their wares, especially with users who haven’t learned all the fancy terminology and so must describe what they see from first principles and be told what to do at a similar level. Even better: such support should be undertaken from memory and not sitting in front of a similarly configured computer.

Although it is a somewhat separate discipline with different constraints, I also suspect that such “over the phone” exercises might help accessibility as well. An inexperienced user may provide different information to that provided by something like a screen reader, where the former may struggle to articulate concepts and the latter may merely describe the environment according to prescribed terms, and where the former may be able to use more flexible powers of description whereas the latter can only rely on the cooperation of other programs to populate a simplistic description of the state of the environment, but the exercise of being a person cut off from the rich graphical scenery and their familiar interaction mechanisms might put the usability and accessibility of the software into perspective for the developers.

The Measure of Progress

But back to the Free Software desktop in general, if only to contemplate notions of progress and to consider whether lessons really have been learned, or whether people would rather not think about the things which went wrong, labelling them as “finished business” or “water under the bridge” and urging people not to bring such matters up again. One participant remarked about how it took six years from 2005 to 2011 for KDE 4 to become as usable as its predecessor. A response to this indicated that this was actually “fantastic” progress given that Google used as much time to make Android “decent”.

Fantastic it may be, but we should not consider the endeavour as a software development project in isolation, with the measure of success being that something was created from nothing in six short years. Indeed, we must consider what was already there – absolutely not nothing – and how the result of the development measures up against that earlier system. As far as getting Free Software in front of people and building on earlier achievements are concerned, those six years can almost be considered six lost years. Nobody should be patting themself on the back upon hearing that someone in 2013 can move from KDE 3 to KDE 4 and feel that at least they didn’t lose much functionality.

The Role of Applications

It was also noted that KDE development now focuses more on application development than on the environment itself. One must therefore ask where we are with regard to parity with the suite of applications running under KDE 3. Here, I can only describe my own experiences, but this should be flattering to any constrained selection of updated applications because of my own rather conservative application choices.

Kontact is usable because I imagine various companies needed it to be usable to stay in business (and even then I don’t know the story of the diversions via Nepomuk and other PIM initiatives that could have endangered that application’s viability); Digikam is usable because the developers remained interested in improving the software and even maintained the KDE 3 version for a while; Okular has picked up where KPDF left off; K3B still works much the same as before. There are presumably regressions and improvements in all these: Kontact, for instance, is much slower in certain areas such as message sorting, but it probably has more robust and coherent PGP and S/MIME support than its predecessor (which may have been suffering from lack of maintenance at both the project and distribution level).

Meanwhile, Amarok has become a disaster with an incoherent interface involving lots of “in the know” controls, and after it stopped playback mid-track for the nth time and needed a complete restart to get sound back, I switched to Minirok out of desperation. Other applications took a permanent holiday, such as Kopete which I don’t miss because my IRC needs are covered by Konversation.

Stuff like Konqueror is still around, despite being under threat of complete replacement by Dolphin, although it has picked up the little “+” and “-” controls that pervade KDE now. Such controls confuse various classes of user through poor visual contrast (a tiny symbol in red or green superimposed on a multicolour icon!) while demanding from such users better than average motor skills (“to open the document aim at the tiny area but not the tiny area within the tiny area”).

Change You Can Believe In?

You wouldn’t think that I appreciate the work done on the Free Software desktop, but I do. What frustrates me and a lot of other people, however, is the way that things that should have been “behind the scenes” infrastructure improvements (Qt 3 being superseded by Qt 4, for instance) that could have been undertaken whilst preserving continuity for users have instead been thrust at those users in the form of unnecessary decisions about which functionality they can afford to lose in order to have a supported and secure system that will not gradually fall apart over time. (Not that KDE is unique in this respect, consider the Python 2 to Python 3 transition and the disruption even such a leisurely transition can cause.)

Exposing change to a group of people creates costs for those people, and when those people have other things than computing as the principal focus in their lives, such change can have damaging effects on their continued use of the software and on the quality of their lives. Following the latest trends, discovering the newest software, or just discovering how their existing software functions since the last vendor-initiated update are all distractions for people who just want to sit down, do some things on the computer, and then go back to their lives. In today’s gadget-pushing society, the productivity benefits of personal computing are being eroded by a fanaticism for showing off new and different things mostly for the sake of them being, well, new and different. Bored children may enjoy the fire-hose of new “apps”, tricks and gadgets, but that shouldn’t mean that everybody else has to be made to enjoy it as well or be considered backward “technophobes” who “don’t understand” or “won’t embrace” new technology.

One can argue that by failing to shield users from the cost of change, especially when the level of functionality remains largely similar, Free Software desktop developers have imperilled their own mission with the result that they now have to make up lost ground in the struggle to get people to use their software. But even to those developers who don’t care about such things, the other criticism that could be levelled against them might be a more delicate matter and more difficult to reconcile with their technical reputation: churning up change and making others deal with it can arguably be regarded as bad software project management and, indeed, bad project management in general.

Maybe such considerations also have something to say about the direction any given community might choose to follow, and whether bold new ideas should be embraced without a thorough consideration of the consequences.

Neo900: And they’re off!

November 1st, 2013

Having mentioned the Neo900 smartphone initiative previously, it seems pertinent to note that it has moved beyond the discussion phase and into the fundraising phase. Compared to the Ubuntu Edge, the goals are fairly modest – 25000 euros versus tens of millions of dollars – but the way this money will be spent has been explained in somewhat more detail than appeared to be the case for the Ubuntu Edge. Indeed, the Neo900 initiative has released a feasibility study document describing the challenges confronting the project: it contains a lot more detail than the typical “we might experience some setbacks” disclaimer on the average Kickstarter campaign page.

It’s also worth noting that as the Neo900 inherits a lot from the GTA04, as the title of the feasibility study document indicates when it refers to the device as the “GTA04b7”, and as the work is likely to be done largely within the auspices of the existing GTA04 endeavour, the fundraising is being done by Golden Delicious (the originators of the GTA04) themselves. From reading the preceding discussion around the project, popular fundraising sites appear to have conditions or restrictions that did not appeal to the project participants: Kickstarter has geographical limitations (coincidentally involving the signatory nations of the increasingly notorious UKUSA Agreement), and most fundraising sites also take a share of the raised funds. Such trade-offs may make sense for campaigns wanting to reach a large audience (and who know how to promote themselves to get prominence on such sites), but if you know who your audience is and how to reach them, and if you already have a functioning business, it could make sense to cut the big campaign sites out of the loop.

It will certainly be interesting to see what happens next. An Openmoko successor coming to the rescue of a product made by the mobile industry’s previously most dominant force: that probably isn’t what some people expected, either at Openmoko or at that once-dominant vendor.

Dell and the Hardware Vendors Page

October 31st, 2013

Hugo complains about Dell playing around with hardware specifications on their Ubuntu-based laptop products. (Hugo has been raising some pretty interesting issues, lately!)

I think that one reason why Dell was dropped from the Hardware Vendors page on the FSFE Fellowship Wiki was that even though Dell was promoting products with GNU/Linux pre-installed, actually finding them remained a challenge involving navigating through page after page of “Dell recommends Windows Vista/Windows 8/Windows Whatever” before either finding a low-specification and overpriced afterthought of a product or the customer just giving up on the whole idea.

Every time they “embrace Linux” I’d like to think that Dell are serious – indeed, Dell manages to support enterprise distributions of GNU/Linux on servers and workstations, so they can be serious, making their antics somewhat suspiciously incompetent at the “home and small office” level – but certainly, the issue of the changing chipset is endemic: I’m pretty sure that a laptop I had to deal with recently didn’t have the advertised chipset, and I tried as hard as possible to select the exact model variant, knowing that vendors switch things out “on the quiet” even for the same model. On that occasion, it was Lenovo playing around.

The first thing any major vendor should do to be taken seriously is to guarantee that if they sell a model with a specific model number then it has a precise and unchanging specification and that both the proper model number and the specification are publicly advertised. Only then can we rely on and verify claims of compatibility with our favourite Free Software operating systems.

Until then, I can only recommend buying a system from a retailer who will stand by their product and attempt to ensure that it will function correctly with the Free Software of your choice, not only initially but also throughout a decent guarantee period. Please help us maintain the Hardware Vendors page and to support vendors and retailers who support Free Software themselves.

(Note to potential buyers and vendors: the Hardware Vendors page does not constitute any recommendation or endorsement of products or services, nor does the absence of any vendor imply disapproval of that vendor’s products. The purpose of the page is to offer information about available products and services based on the experiences and research of wiki contributors, and as such is not a marketplace or a directory where vendors may request or demand to be represented. Indeed, the best way for a vendor to be mentioned on that page is to coherently and consistently offer products that work with Free Software and that satisfy customer needs so that someone may feel happy enough with their purchase that they want to tell other people about it. Yes, that’s good old-fashioned service being recognised and rewarded: an unusual concept in the modern world of business, I’m sure.)

The Ben NanoNote: An Overlooked Hardware Experimentation Platform

October 30th, 2013

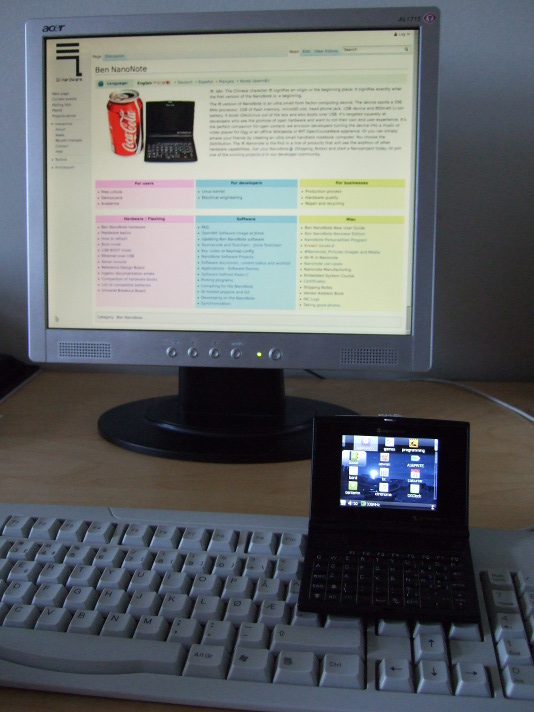

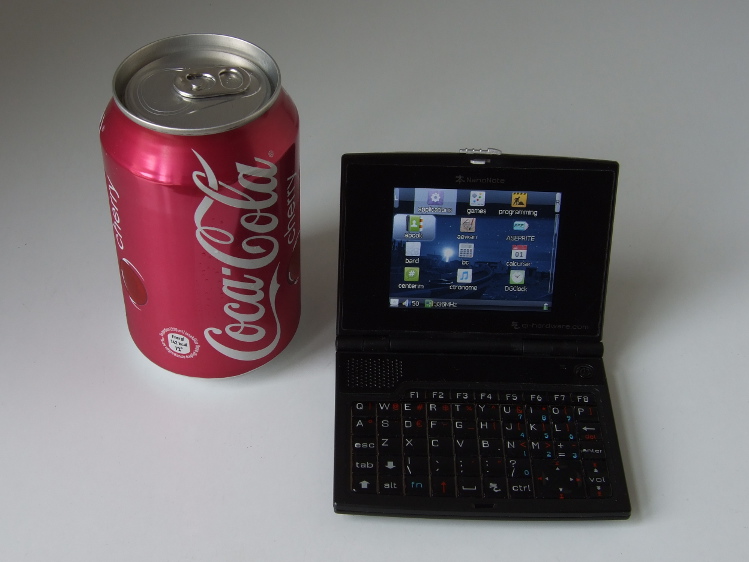

The Ben NanoNote is a pocket computer with a 3-inch screen and organiser-style keyboard announced in 2010 as the first in a line of copyleft hardware products under the Qi-Hardware umbrella: an initiative to collaboratively develop open hardware with full support for Free Software. With origins as an existing electronic dictionary product, the Ben NanoNote was customised for use as a general-purpose computing platform and produced in a limited quantity, with plans for successors that sadly did not reach full production.

The Ben NanoNote with illustrative beverage (not endorsed by anyone involved with this message, all trademarks acknowledged, call off the lawyers!)

When the Ben (as it is sometimes referred to in short form) first became known to a wider audience, many people focused on those specifications common to most portable devices sold today: the memory and screen size, what kind of networking it has (or doesn’t have). Some people wondered what the attraction was of a device that wasn’t wireless-capable when supposedly cheaper wireless communicator devices could be obtained. Even the wiki page for the Ben has only really prominently promoted the Free Software side of the device, mentioning its potential for making customised end-user experiences, and as an appliance for open content or for music and video playback.

Certainly, the community around the Ben has a lot to be proud of with regard to Free Software support. A perusal of the Qi-Hardware news page reveals the efforts to make sure that the Ben was (and still is) completely supported by Free Software drivers within the upstream Linux kernel distribution. With a Free Software bootloader, the Ben is probably one of the few devices that could conceivably get some kind of endorsement for the complete absence of proprietary software, including firmware blobs, from organisations like the FSF who naturally care about such things. (Indeed, a project recommended by the FSF whose output appears to be closely related to the Ben’s default software distribution publishes a short guide to installing their software on the Ben.)

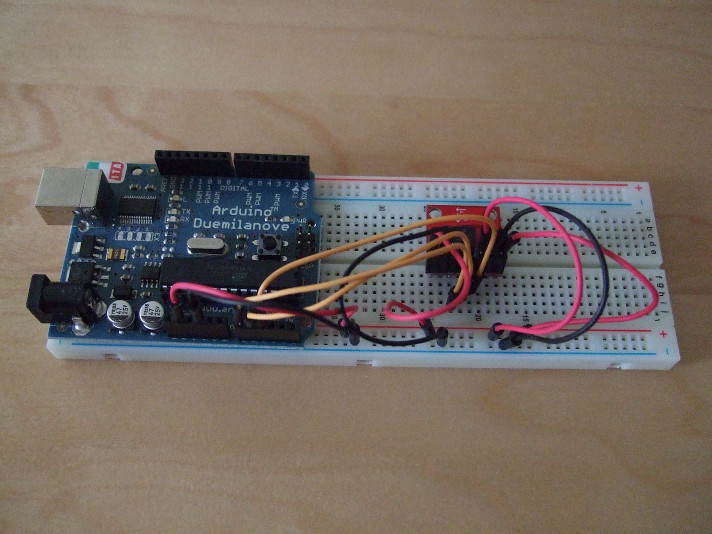

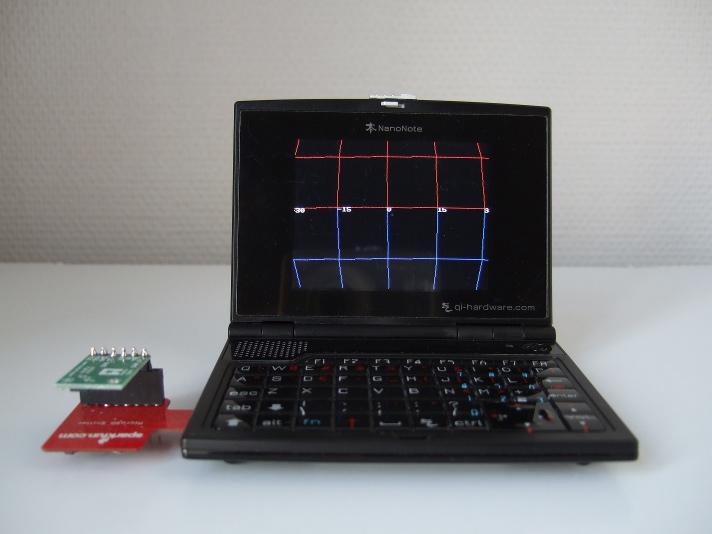

But not everybody focused only on the software upon learning about the device: some articles covered the full range of ambitions and applications anticipated for the Ben and for subsequent devices in the NanoNote series. And work got underway rather quickly to demonstrate how the Ben might complement the Arduino range of electronics prototyping and experimentation boards. Although there were concerns that the interfacing potential of the Ben might be a bit limited, with only USB peripheral support available via the built-in USB port (thus ruling out the huge range of devices accessible to USB hosts), the alternatives offered by the device’s microSD port appear to offer a degree of compensation. (The possibility of using SDIO devices had been mentioned at the very beginning, but SDIO is not as popular as some might have wished, and the Ben’s microSD support seems to go only as far as providing MMC capabilities in hardware, leaving out desirable features such as hardware SPI support that would make programming slightly easier and performance substantially better. Meanwhile, some people even took the NanoNote platform to a different level by reworking the Ben, freeing up connections for interfacing and adding an FPGA, but the resulting SIE device apparently didn’t make it beyond the academic environments for which it was designed.)

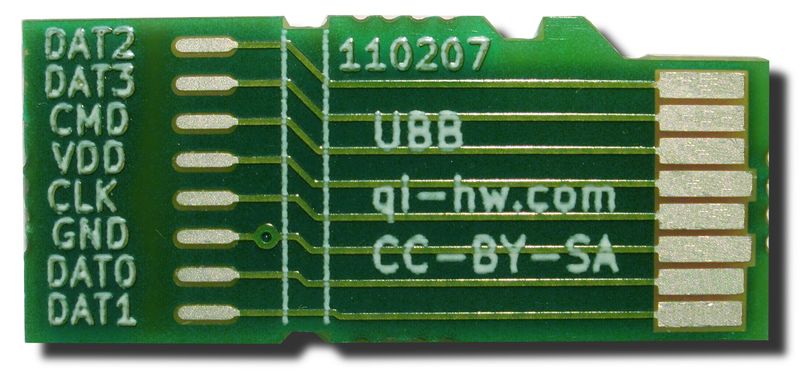

Thus, the Universal Breakout Board (UBB) was conceived: a way of “breaking out” or exposing the connections of the microSD port to external devices whilst communicating with those devices in a different way than one would with SD-based cards. Indeed, the initial impetus for the UBB was to investigate whether the Ben could be interfaced to an Ethernet board and thus provide dependency-free networking (as opposed to using Ethernet-over-USB to a networked host computer or suitably configured router). Sadly, some of those missing SD-related features have an impact on performance and practicality, but that doesn’t stop the UBB from being an interesting avenue of experimentation. To distinguish between SD-related usage and to avoid trademark issues, the microSD port is usually referred to as the 8:10 port in the context of the UBB.

(The UBB image originates from Qi-Hardware and is CC-BY-SA 3.0 licensed.)

Interfacing in Comfort

A lot of experimentation with computer-controlled electronics is done using microcontroller solutions like those designed and produced by Arduino, whose range of products starts with the modestly specified Arduino Uno with an ATmega328 CPU providing 32K (kilobytes) of flash memory and 2K of “conventional” static RAM (SRAM). Such specifications sound incredibly limiting, and when one considers that many microcomputers in 1983 – thirty years ago – had at least 32K of “conventional” readable and writable memory, albeit not all of it being always available for use on some machines, devices such as the Uno do not seem to represent much of an advance. However, such constraints can also be liberating: programs written to run in such limited space on the “bare metal” (there being no operating system) can be conceptually simple and focus on very specific interfacing tasks. Nevertheless, the platform requires some adjustment, too: data that will not be updated while a program runs on the device must be packed away in the flash memory where it obviously cannot be changed, and data that the device manipulates or collects must be kept within the limits of the precious SRAM, bearing in mind that the program stack may also be taking up space there, too.

As a consequence, the Arduino platform benefits from a vibrant market in add-ons that extend the basic boards such as the Uno with useful capabilities that in some way make up for those boards’ deficiencies. For example, there are several “shield” add-on products that provide access to SD cards for “data logging“: essential given that the on-board SRAM is not likely to be able to log much data (and is volatile), and given that the on-board flash memory cannot be rewritten during operation. Other add-ons requiring considerable amounts of data also include such additional storage, so that display shields will incorporate storage for bitmaps that might be shown on the display: the Arduino TFT LCD Screen does precisely this by offering a microSD slot. On the one hand, the basic boards offer only what people really need as the foundational component of their projects, but this causes add-on designers to try and remedy the lack of useful core functionality at every turn, putting microSD or SD storage on every shield or extension board just because the user might not have such capabilities already.