A few months ago, I had the opportunity to combine two of my interests: retrocomputing and Python programming. The latter needs little additional explanation, but the former perhaps requires a few more words. Retrocomputing is the study and use of computing equipment from an earlier era in computing, where such equipment is typically no longer in use, or is no longer in widespread use. My own experiences with microcomputers began in the 1980s and are largely centred upon those manufactured by Acorn Computers, such as the Acorn Electron and BBC Microcomputer.

Some History

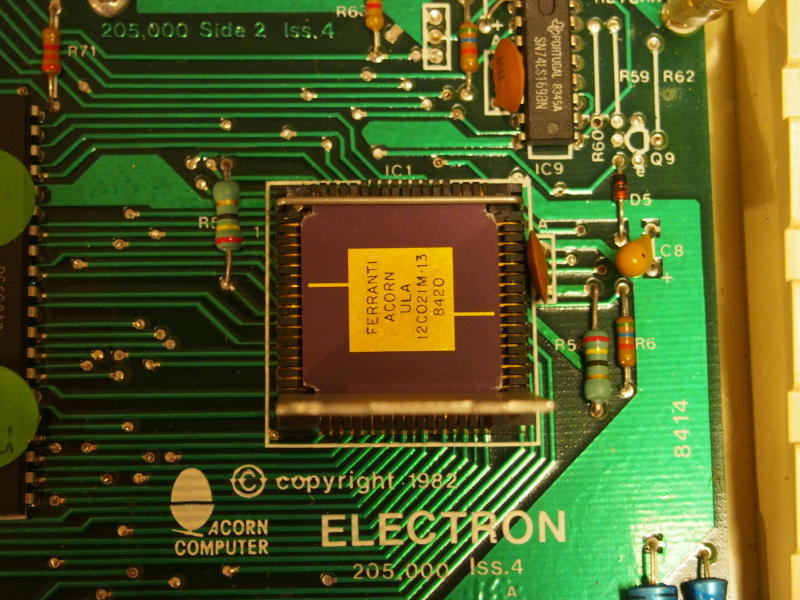

One of my earlier initiatives was to attempt to document and understand the functioning of the Acorn Electron’s ULA integrated circuit: the Uncommitted Logic Array employed in the computer to generate video and perform input/output tasks. When Acorn decided to make the Electron as a variant of the BBC Microcomputer, the engineers merged many of the functions performed by separate chips into a single one, for several good and not-so-good reasons:

- To reduce system complexity: having to connect several components and make sure that they all work correctly and in time with each other can be challenging, and it is arguably best to reduce the number of things that can go wrong by just reducing the number of things involved in the first place.

- To reduce system cost: production becomes less complicated and savings can potentially be realised by combining discrete components.

- To deepen the organisation’s experience with integrated circuit design: this being the company that developed the ARM architecture and eventually brought the first ARM chipset (CPU, audio/video controller, memory management unit, and input/output controller) to market.

- To make a proprietary component that others could not readily clone: this being something of an obsession in the early 1980s marketplace.

Now, the ULA has the job of reading from memory and translating what it reads into a sequence of colour values, thus generating a picture on the screen. However, it has the annoying limitation of locking the CPU out of the memory (in fact, only the RAM which resides in a certain region) while it generates each line of the displayed image. Depending on which “screen mode” is selected (determining the resolution and colour depth), it may still let the CPU access the RAM at a lower speed, or it may effectively suspend the CPU for the entire time taken to generate a single horizontal display line.

Consequently, the Acorn Electron is considerably slower than the BBC Microcomputer for this reason: the BBC Micro employs faster memory and lets the CPU and its own video circuitry take turns with the memory while they both run at full speed; the Electron used cheaper memory as another cost-saving measure; reviews of the Electron, while generally positive about getting BBC Micro features for less, tended to note this performance degradation with some disappointment.

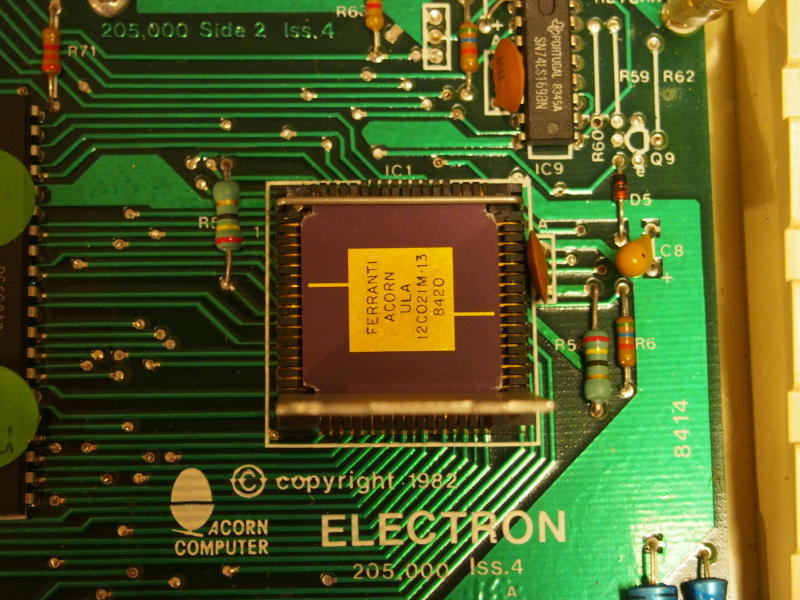

The Acorn Electron ULA (with socket cover/heatsink removed)

Some Background

Normally, the matter of the CPU stalling for much of its time would be considered a disadvantage, but my brother and I were having a discussion about software running from ROM (or, in fact, in the area of memory not affected by the ULA), with the pitfalls of such software needing to access the RAM and potentially becoming stalled as the CPU finds itself waiting for the ULA to do its work. Somehow the notion arose that the ULA effectively provides a kind of synchronisation mechanism for software needing to run in the period between display lines.

So, a program can read instructions from ROM and then, when it needs to know that the display is not being updated, it can attempt to access RAM. Whether or not the program stalls remains unknown to the program itself, but when it gets the result of accessing the RAM – perhaps immediately, perhaps after a few microseconds – it can be certain that the ULA is not accessing the RAM because it just did so itself.

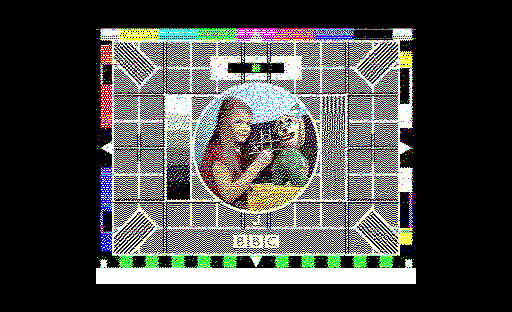

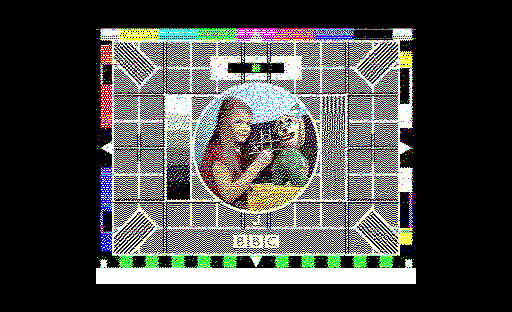

An image showing the display update region (the "test card" picture) when the ULA accesses memory, with the black border indicating the region (or time period) during which the CPU may access the lower region of the Electron's memory.

(See the BBC Test Cards for the origin of the above picture.)

One might wonder what kind of program would benefit from synchronising itself to the display line periods. Well, one thing that tended to happen back in the microcomputing era, was the trick of reprogramming the display palette – the selection of colours shown on screen – so that a greater number of colours can be displayed simultaneously on the screen than would normally be the case for that particular display configuration. For example, a screen mode normally offering only four colours could instead offer the full range – eight “proper” colours on an Electron – if it switched the palette during screen updates. Even a screen mode offering only two colours could offer eight by employing palette switching.

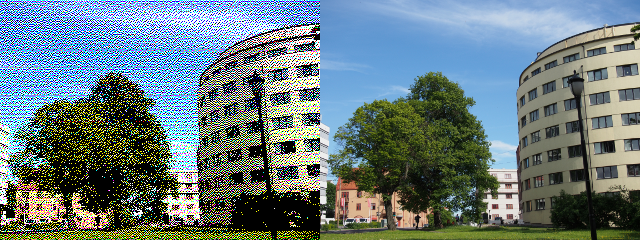

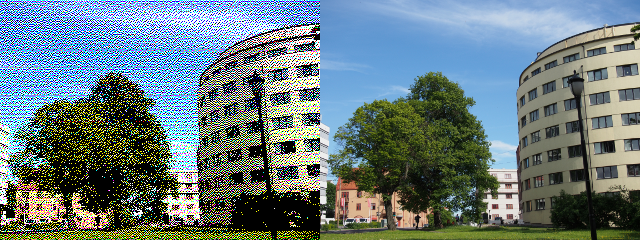

And with a certain amount of experimentation, a working solution was eventually delivered (with only limited input needed from my side). By running software in a ROM (or from RAM mapped into the same area of memory as a ROM), it became possible to reliably change the palette on a line-by-line basis, bridging the gap between a medium-resolution four-colour mode and a hypothetical eight-colour version that would only become available on Acorn’s ARM-based microcomputers. Although only four colours can be used per display line, each of the 256 display lines can employ four-colour combinations of the full eight colours, not quite making an eight-colour mode – which would, of course, allow eight colours on every display line – but still permitting graphical output much closer to a true eight-colour mode than can be contemplated with a restrictive four-colour mode.

Rainbow lorikeets on a lawn (left: 4 colours from 8 per display line; right: 8 colours per display line)

Palette Optimisation

With the trick in place to switch the palette on demand, all that remained was to make a program that could take an input image and to optimise the colours so that…

- Only the eight permitted colours (black, white, primary and secondary colours) are used in the image.

- No pixel row (display line) employs more than four different colours.

Expectations were rather low at first. First of all, in this era of bountiful quantities of fresh imagery, most pictures appear to have plenty of colours and are photographs, and so the easiest images to use are the ones that first need to be reduced in both resolution and colour depth. And once this is done, the job of optimising the colours to meet the second of the above criteria is required. So, initially, very simple techniques were employed to do both of these things.

Later, after some discussions, it appeared that integrating the two processing activities and, crucially, applying basic dithering and error propagation techniques, made it possible to represent complicated “deep-colour” images within the limited display representation.

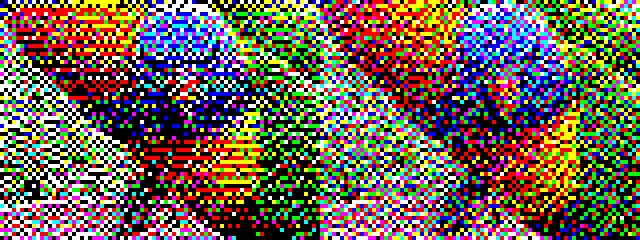

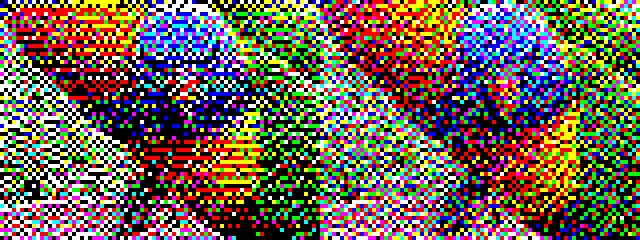

Magnified details of the two representations

Closer examination of the above images reveals how the algorithm attempts to spread the responsibility of representing colours across rows, being restricted to the choice of four colours (in the left image) to produce the appropriate tones that are more readily encoded using eight colours (in the right image).

Tuning the Implementation

To perform the optimisation process, I wrote a program which took an input image, rotated and scaled it to the target resolution, and processed the colours by inspecting the pixel data on each horizontal line (or row) of the image, calculating the appropriate four-colour combination for a line and generating suitable pixel data appropriate for this restricted palette. Since I am probably most comfortable with Python, and since Python also has various convenient image-processing libraries, I found myself developing a short Python program to do the work.

Now, Python doesn’t usually exhibit the highest performance, particularly for tasks such as this, and as the experimentation with different approaches started to lessen, with the most rewarding approaches making themselves evident, and with the temptation to convert lots of images just to see the results, my attentions turned to speeding up the program. Since I had been involved with packaging the Shedskin Python-to-C++ compiler for Debian, and thus the package was right there for me to use, it made sense to give it a try on this code.

At this point, the program was taking around 40 seconds to convert a 16 megapixel photographic image into the appropriate output representation. Despite using the Python Imaging Library to do the rotation and scaling, visiting each pixel in a Python program and doing some simple statistical and arithmetic operations was taking up rather a lot of time. In the past, I have used various “numeric” Python extensions – usually the ones supported by pygame – but things have moved on somewhat incoherently since then, and I also wanted to keep my code straightforward and readable, which is often something that is lost when making code “numeric”.

Time for Shedskin

I have used Shedskin before, and the first thing to think about when using it is how it will interact with non-Python code. Shedskin takes Python code and generates C++ which must then be compiled. If a whole program is translated to C++, the resulting executable can be run with no further work necessary. However, the program of interest here uses libraries that are actually implemented in C and are delivered as shared libraries that are loaded by CPython (the Python virtual machine implementation written in the C programming language). Shedskin cannot generally translate such a program in its entirety.

From the earliest days of Python, it was (and has remained) a common practice to first write library code in Python, desire better performance, and to then rewrite much of that code in the C programming language against the Python/C API (or CPython API) as an “extension module”, which is what these problematic shared libraries are. Such libraries act as part of the CPython virtual machine, more or less, and with suitable implementation choices made for performance, everything using such libraries will run much more quickly. Unfortunately, but understandably, Shedskin doesn’t seek to interact closely with the CPython implementation: it produces C++ code that works with its own runtime libraries.

So, instead of working with a single program file, I split my program up into a main program which deals with CPython extensions such as the Python Imaging Library, whose JPEG and PNG manipulation facilities are too convenient to abandon, along with a library module that does all the computation for this particular application. The library would provide its own image abstraction for pixel-level accesses, but be given the pixel data obtained by the main program, returning the processed data to the main program for saving to a file. By only compiling the library, Shedskin can produce a standalone library file containing hopefully high-performance implementations of the original Python code.

But how can such a library constructed by Shedskin be used? Would we now need to somehow translate the main program into C or C++ in order to be able to use it? Fortunately, but slightly confusingly, Shedskin can also generate the necessary CPython API wrapper around the translated code, making it possible for CPython to load this newly-created library after all.

(One might wonder how this is possible, but if one considers that arbitrary C or C++ code can be wrapped using the CPython API, with the values being sent in and out of a library only being converted at the interface, Shedskin has the luxury of generating something that lives by its own rules internally, with the wrapper doing the necessary “marshalling” of the values as they go in and come out. Such a wrapped library might be frowned upon in the Python world, not being a sophisticated extension module that takes full advantage of the CPython API, but such libraries were, and probably still are, the “bread and butter” of Python’s access to a wide array of tools and technologies.)

Knowing that this is a reasonable approach, I experienced a moment of excessive ambition. I tried to take the newly-broken-out library and compile it using the appropriate option:

shedskin -e optimiser.py

This took quite some time, and things did not go well…

*** SHED SKIN Python-to-C++ Compiler 0.9.2 ***

Copyright 2005-2011 Mark Dufour; License GNU GPL version 3 (See LICENSE)

[analyzing types..]

****************************88%

*WARNING* reached maximum number of iterations

********************************100%

[generating c++ code..]

*WARNING* 'get_combinations' function not exported (cannot convert argument 'c')

*WARNING* 'get_colours' function not exported (cannot convert return value)

*WARNING* 'balance' function not exported (cannot convert argument 'd')

*WARNING* optimiser.py: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {None, int, tuple}

*WARNING* optimiser.py: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {float, int, tuple2}

*WARNING* optimiser.py: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {float, int, tuple}

*WARNING* optimiser.py: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {int, tuple}

*WARNING* optimiser.py: variable 'data' has dynamic (sub)type: {None, int, tuple}

*WARNING* optimiser.py: variable (class SimpleImage, 'data') has dynamic (sub)type: {None, int, tuple}

And then there were many more lines of a more specific nature:

*WARNING* optimiser.py:41: function distance not called!

*WARNING* optimiser.py:50: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {None, int, tuple}

*WARNING* optimiser.py:53: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {None, int, tuple}

*WARNING* optimiser.py:57: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {float, int, tuple2}

*WARNING* optimiser.py:57: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {int, tuple}

And so on. Now, if you are thinking that this will probably not end well, you would be right. Running make gives plenty of errors looking as scary as this…

optimiser.cpp: In function '__shedskin__::list<__shedskin__::tuple2<__shedskin__::tuple2<int, int>*, double>*>* __optimiser__::list_comp_0(__shedskin__::pyiter<double>*)':

optimiser.cpp:76:17: error: base operand of '->' is not a pointer

optimiser.cpp:77:21: error: base operand of '->' is not a pointer

optimiser.cpp:78:68: error: invalid conversion from '__shedskin__::tuple2<int, int>*' to 'int' [-fpermissive]

In file included from /usr/share/shedskin/lib/builtin.hpp:1204:0,

from optimiser.cpp:1:

/usr/share/shedskin/lib/builtin/tuple.hpp:211:28: error: initializing argument 2 of '__shedskin__::tuple2<A, B>::tuple2(int, A, B) [with A = int; B = double]' [-fpermissive]

optimiser.cpp:78:70: error: no matching function for call to '__shedskin__::list<__shedskin__::tuple2<__shedskin__::tuple2<int, int>*, double>*>::append(__shedskin__::tuple2<int, double>*)'

optimiser.cpp:78:70: note: candidate is:

In file included from /usr/share/shedskin/lib/builtin.hpp:1203:0,

from optimiser.cpp:1:

/usr/share/shedskin/lib/builtin/list.hpp:96:25: note: void* __shedskin__::list<T>::append(T) [with T = __shedskin__::tuple2<__shedskin__::tuple2<int, int>*, double>*]

/usr/share/shedskin/lib/builtin/list.hpp:96:25: note: no known conversion for argument 1 from '__shedskin__::tuple2<int, double>*' to '__shedskin__::tuple2<__shedskin__::tuple2<int, int>*, double>*'

Of course, it would be unfair to expect this to have worked: Shedskin did indeed give us plenty of warnings! But we should at least try and understand such warnings if we are to make progress. After a few more iterations of this bold strategy, I realised that I had started out in the wrong fashion, presenting Shedskin with code that is too dynamic (and ambiguous) for it to reasonably infer sensible types and produce a compilable C++ representation.

First Things First

I started out by reintroducing some necessary changes gradually. First of all, I made a branch of my code committing the special image abstraction to be used in any future Shedskin-compiled version. Meanwhile, I looked at some things that might generally be performance-degrading in Python, and which might also help Shedskin deduce the program types more readily.

One thing that I had done in the initial implementation was to freely use sequences to represent colour triplets: the red, green and blue values. I was using code like this:

def invert(srgb):

return tuple(map(lambda x: 1.0 - x, srgb))

This might be elegant – there’s no separate treatment of each element in the triplet – but there is likely to be more overhead in treating the triplet as a sequence, iterating over it, and so on. Moreover, Shedskin is likely to see objects appearing from a collection without any idea of what was put into that collection to start with. So, more mundane code was introduced in its place:

def invert(srgb):

r, g, b = srgb

return 1.0 - r, 1.0 - g, 1.0 - b

Such changes reduced the processing time from around 35 seconds to around 25 seconds. After various other performance modifications, such as avoiding the repeated computation of common values, this became around 18 to 19 seconds. Interestingly, merging such modifications into the branch with the special image abstraction reduced the running time to around 16 to 17 seconds. But at this point, obvious optimisation opportunities were more or less exhausted.

It then became time for another attempt to present this to Shedskin. This time, instead of calling the main program main.py and the library optimiser.py, which is not particularly intuitive, I retained the name of the main program as optimiser.py and used the traditional optimiserlib.py naming for the library:

shedskin -e optimiserlib.py

This completed without any warnings, and running make produced a library file, optimiserlib.so, that Python recognises as an extension module. Running the program produced a palette-optimised image in just under 9 seconds!

Making the Difference

So, what were the differences that made Shedskin accept the library code? Since the splitting up of the code into two files makes comparisons between versions awkward, we can first compare the version of the program before our preparatory work with the version of the program that fed into our Shedskin version. There are four areas of changes:

- The introduction of that image abstraction class – SimpleImage – to be used to manipulate images instead of using Python Imaging Library objects. (In fact, this is only used initially as a container for the raw pixel data, with such data being passed to library functions, as described below.)

- Modifications to access the different components of colour triplets explicitly.

- Some “common sense” performance modifications, avoiding the repeated computation of things that always produce the same result anyway.

- Some local name adjustments.

This final point is something that the Shedskin documentation mentions prominently, but it can be easy to forget. Consider the following code (in the balance function of the library module):

dd = dict([(value, f) for f, value in d])

Originally, this looked like this:

d = dict([(value, f) for f, value in d])

This earlier version just reverses a dictionary mapping and assigns the result to the name of the original dictionary. Although this seems harmless enough, Shedskin’s analysis would be complicated substantially by having to deal with a name being reassigned and potentially being associated with completely different kinds of objects, even if in this case we are only dealing with dictionaries. (Even if the same type were only ever involved, as we see here, it would also prevent any analysis being done on the nature of the keys and values in the dictionaries.)

We can see the effect of this by trying to compile the functioning version with the earlier naming scheme reintroduced. First, we see a warning like this:

*WARNING* 'balance' function not exported (cannot convert argument 'd')

Since Shedskin propagates type information around the program, this leads to other problems:

*WARNING* optimiserlib.py: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {float, int, tuple2}

*WARNING* optimiserlib.py: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {float, int, tuple}

*WARNING* optimiserlib.py: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {int, tuple}

*WARNING* optimiserlib.py: variable (function (function balance, 'list_comp_0'), 'value') has dynamic (sub)type: {int, tuple}

*WARNING* optimiserlib.py: variable (function (function balance, 'list_comp_1'), 'f') has dynamic (sub)type: {float, int, tuple2}

*WARNING* optimiserlib.py: variable (function (function balance, 'list_comp_1'), 'value') has dynamic (sub)type: {int, tuple}

And later in the messages, the more specific errors indicate the problem and its consequences:

*WARNING* optimiserlib.py:100: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {float, int, tuple2}

*WARNING* optimiserlib.py:100: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {float, int, tuple}

*WARNING* optimiserlib.py:100: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {int, tuple}

*WARNING* optimiserlib.py:102: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {float, int, tuple2}

*WARNING* optimiserlib.py:102: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {float, int, tuple}

*WARNING* optimiserlib.py:103: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {float, int, tuple2}

*WARNING* optimiserlib.py:103: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {float, int, tuple}

*WARNING* optimiserlib.py:104: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {float, int, tuple2}

*WARNING* optimiserlib.py:104: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {float, int, tuple}

*WARNING* optimiserlib.py:105: class 'list' has no method 'items'

*WARNING* optimiserlib.py:105: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {float, int, tuple2}

*WARNING* optimiserlib.py:105: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {float, int, tuple}

*WARNING* optimiserlib.py:105: expression has dynamic (sub)type: {int, tuple}

And so on. Such warnings, which will cause errors if one tries to compile the result, can seem very intimidating, but within all these details the cause should be identifiable.

But another important aspect of the successful translation of the library module should not be forgotten: it is the matter of choosing the right initial functionality to give to Shedskin. Instead of trying to compile everything, it makes sense to concentrate on things like functions which are fairly self-contained, which do not call potentially vast regions of other program functionality, and which are invoked often, especially in loops that take a long time. Migrating a small piece of functionality at a time helps to keep the troubleshooting activity manageable.

By using the SimpleImage class as a convenient staging post for pixel data, simple library functions could be migrated first, and the library could be kept ignorant of the abstractions being maintained in the main program. Later on, as we shall see below, such abstractions and functions that require them could then be migrated themselves.

Broadening the Scope

With some core functionality migrated to a compilable extension module, it becomes possible to give other things the Shedskin treatment. At the start of the second attempt to get Shedskin to compile the code, quite a few functions were still being run by the CPython virtual machine, notably various image operations. With the functions called by these operations already migrated, it becomes possible to move each of these operations over into the extension module. The expectation here is that since these functions can now call each other without the overhead of the CPython API, as well as avoiding running code in the virtual machine, further performance improvements will occur.

And since Shedskin’s own runtime library supports certain Python standard library modules in accelerated form, it becomes interesting to migrate operations that employ such module functionality. For example, the get_combinations function can be moved to take advantage of Shedskin’s itertools implementation. And in addition to just moving functions, classes can also be compiled by Shedskin and potentially accessed more quickly, while remaining accessible to normal Python code that hasn’t been compiled.

Not all of these optimisations give the boost in performance that might be hoped for, perhaps even bringing performance penalties when first introduced. But it is important to look beyond any current, small optimisation to future optimisations that the accumulation of those small optimisations will permit. Moving the SimpleImage class into the extension module permits the migration of other code, with the consequence that the program when run takes around 6 seconds instead of 9 seconds: the apparent optimisation barrier is overcome, leading to yet more gains!

Some Conclusions

It is possible to make very useful performance gains just by revisiting code and writing it in a way that suits the language implementation. Starting out with an execution time of around 40 seconds, it was possible to make the program run in closer to 15 seconds, and that might have been enough for occasional conversion of images. But by adopting Shedskin and applying it to a subset of the program’s functionality, an execution time of 9 seconds was initially obtained. This might not be quite as impressive as the earlier two-and-a-half fold reduction in time (or, of course, a two-and-a-half fold increase in throughput), but it was obtained with little additional effort, with admittedly some planning for it being incorporated into the earlier optimisation work.

Ultimately, reaching around 6 seconds of execution time means that Shedskin was indeed able to more or less match earlier performance gains, but again with little actual optimisation effort. And one can argue that merely using Shedskin helped to inform those earlier gains, anyway. Regardless of what should take the credit, the program ended up running almost seven times faster than when we started out on this journey.

Tools like Shedskin have a slightly controversial place in the Python world. People like to point out that Shedskin really only compiles a “restricted subset” of Python: one that Shedskin is able to analyse. And as the above exercise demonstrates, modifications to programs are likely to be required to take advantage of it. But the resulting programs are still Python programs, and the CPython virtual machine will still run them, just slower – three times slower in this case – than if they were compiled.

Authors of tools like Shedskin and alternative implementations of the Python language have a tough decision to make. They must either deal with the continuously changing “full-fat” version of the language, with new features being added all the time that they have to support, with the risk that they will never catch up and never be considered a “proper” implementation. Or they must impose limitations on the form of the language and the features they support, knowing that even if their software accepts programs written in Python, it will be marginalised and regarded as a distraction from “proper” Python programming. And yet, Python as delivered by CPython offers little in the way of things that Shedskin and similar tools seek to offer, so it should be no wonder that such tools have come to exist.

Instead, one might wonder why it is that the language must continue to evolve in ways that frustrate static analysis and enhancements to program performance and scalability. Indeed, my own interests in the analysis of Python code have been somewhat rekindled by this exercise, but unlike the valiant efforts of other developers (such as the author of Nuitka and his continuing quest to support the compilation of “full-fat” Python), I have no intention of using Python as my gold standard. In essence, Python is and has been a productive language to use – that is why I have used it here and many times before – but the very nature of the language should be open to question and review.

If, by discarding features, something like Python can be more predictable and better-performing, why would exploring this avenue of inquiry be a bad thing? Shedskin shows us that there are benefits in doing so, and I hope that this article has also shown some practical techniques for using and understanding the tool. And maybe this will encourage me and others to make some more progress with our own Python program analysis efforts as well, if only to offer alternatives that seek to deliver on some of the unrealised promise and potential that Python seemed to offer back when we first discovered it, so many years ago now.

An architectural picture from Oslo with the left version using 4 colours from 8 on every display line, the right version being a scaled version of the original.