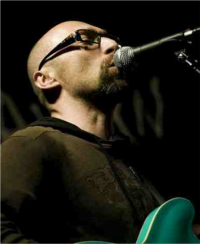

Massimo Babieri is an IT manager at the Earth Science Department, of the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia. As well as holding a Ph.D in Geology, Massimo leads the band The Radiostars, releasing their music under a Free license. As well as being a member of the LUG Scandiano, he has been very active in the ongoing success of the PDFreaders campaign in Italy.

Chris Woolfrey: As an artist who believes in the merits of Free culture and Free Software, why do you think it is that more musicians, photographers, and film makers haven’t gone down this road?

Massimo Babieri: There are a few reasons why artists don’t usually use Free licenses. The first is probably caused by the money: if you sell a lot of records you may collect a lot of money, even from royalties, and probably most artists don’t want to lose that money. But I think there is also a problem of knowledge. A lot of artists don’t know what “authors’ rights” really means and they think that if you want to gain paternity over your work, or if you want to protect your art from theft of paternity, you have to do some formal stuff like join a society of authors and publishers, like SIAE, ASCAP, and so on. What I’m trying to say is that many artists don’t know what their rights are when it comes to their art.

CW: Radiohead come to mind. Back in 2007 when they released In Rainbows, it was a bold move, as such a big band, when they told fans they could pay what they wanted for their album. But they didn’t change the copyright. Should they have?

“Music is as old as man, but copyright is very, very new”

MB: Probably asking people to pay what they want for Radiohead’s album is a good thing for music and for people too because every kind of art is culture, and I think you shouldn’t have to pay to get culture; everybody should be able to take benefit from it. Radiohead didn’t use a new license for their album but I think that it’s great that everybody can listen to it. Every artist holds the rights to their art so I do not think there’s a wrong here, as long as the music can be enjoyed freely. Next year The Beatles’ first single, ‘Love Me Do’, should become Public Domain License. This is a great thing for culture.

CW: I suppose the question is whether art can be enjoyed freely, though, without the release of copyright?

MB: If you think about music, it’s maybe as old as man, but the terms of copyright are very, very young; the idea that you can make money because someone plays one of your songs on the radio is very young. Culturally, we say “play music” and not “work music”, because music is a part of humanity, is a part of our culture, and copyright is only a recent invention. For that reason it should be quite natural for an artist to use a Free license.

CW: Do you use the free license because you think it represents what’s natural about music?

MB: Yes, but also because I like to get my music to people. I like it when someone says to me “Hey, I listened to your album and I like this song…”

CW: So, Free licensing also has a commercial appeal?

MB: I didn’t make any money with Jamendo, but I think it can represent commercial appeal for Free art. You have to consider that, for a musician, money comes also from the selling of the album and from shows, so a Free licence can be also an important way to promote music.

CW: Do you think then that there is a greater need for education about Free Culture, as there is for Free Software? Do you see a need to set an example by producing and promoting Free art?

“Free art means Free education”

MB: Free art means Free education. There are a lot of things that we can learn form art. Using a Creative Commons (CC) license can be a good way to promote your art and make it known to a wider audience. For the artist it also represents the control that you have on your art. Our first three albums were, unfortunately, published with ‘All Rights Reserved’ licenses. In 2008 we moved away from that, to CC, and now we feel more free with our music.

CW: And more able to make it the way that you want to?

MB: Exactly!

CW: Let’s hope more follow your example! Free art is getting more popular, and now that there is more of a public debate about it do you think it’s inevitable that the majority of art might once again become “Free”? Isn’t that part of what worries the industry about ‘piracy’?

MB: I hope that art will again become Free, but I strongly regret that piracy exists because every artist has their rights on their own art and we have to respect that. I hope that art becomes Free, but in a natural and legal way, with Free licenses adopted by artists. I think that things will change, maybe in few decades, maybe a few hundred years.

CW: You’ve spoken about art as a cultural tool, and its use in education; another important part of culture is history. Document Freedom Day is coming up at the end of March: how important is it for you that culture which is stored digitally remains Free for future generations?

MB: It’s absolutely fundamental, of course! But not only if we think about the story in decades, centuries or millennia; it’s fundamental even if we think about the few years that make up our own lives. Open Document Formats are the only way to keep alive the possibility of choosing your software, protecting you from vendor lock-in and assuring the life of your data.

CW: Do you see Document Freedom Day and the PDFreaders Campaign as twin warriors, in that case?

“The value of these campaigns lies in the opportunity to speak to public bodies”

MB: Well I think that the PDFreaders campaign is mainly focused on neutrality, and this is the thing: that’s more easy to understand from the point of view of a public institution. When we are able to open that dialogue with them there is often the opportunity to talk with them about FS and Open Standards. So I think that the high value of both campaigns is that we get the opportunity to speak with public bodies. I’m really enthusiastic about this approach: I sometimes think that if you want to bring FS and Open Standards to public bodies you simply have to talk with them. Talking to people is the best way to help FS and Open Standards, and to protect both; there are a lot of people that do not consider the value of their data.

I think there are only two possibilities: either we talk with people and try to convince them to use Open Standards, or we simply wait for the day when most people won’t be able to access their data or choose the software that they use. Recently I’ve seen this second case at work: one of my colleagues uses Macromedia FreeHand. Adobe Systems acquired Macromedia in 2005 and started to control the line of Macromedia products, including Freehand. In 2007, Adobe said that it would discontinue development and support of the program. So what about his data? I took this opportunity to convince him to use Inkscape and to save his work in .svg, which is an Open Standard.

That’s the risk here: dependence on a single company. If you use a proprietary file format you will of course always be locked with the company who own this format; if we continue to use proprietary file formats we will lock future generations with the company who own the format, choosing not just for ourselves but also for future generations.

Fortunately there are a lot of people and technologies which already use Open Standards. We, the LUG Scandiano, recently convinced our Municipality to distribute files from their website using only Open Standards.

CW: Lobbying and activism have an important role to play. But is education the best place to fight the battle? Do you find that, working in a university, a lot can be done in education?

MB: Yes, by talking about education we are talking about the future. As an FS lover I think that school should never propose to the students the use of non-Free Software. And of course many good students and teachers could benefit form FS, but it’s not always easy to persuade teachers to change. I recently acheived an important goal in my department. For 3 years we had the Microsoft Campus contract for the use of MS Office; after a lot of pressing I persuaded the leader of my department to stop paying for it. It can take a long time but I think that insisting every day we can obtain results.

CW: With smaller campaigns like these, plus the bigger campaigns run by groups like FSFE, we might really be on to something!

MB: Yes, I think! And I hope. If people talk about FS to their friends, talk about FS to their boss, talk

about FS to the mayor of their city, and so on, I really think so.