Questions of privacy, security and control have occupied me for a long time, both personally and professionally. In fact it was a significant aspect of my decision to switch focus from the Free Software Foundation Europe to Kolab Systems: I wanted to reduce the barriers to actually putting the principles into practice. That required a professional solution which would offer all the benefits and features people have grown accustomed to, but would provide it as high quality Open Source / Free Software with a strong focus on Open Standards.

What surprised me at the time was the amount of discussions I had with other business people and potential customers whether there was really a point in investing so much into such a business and technology since Google Apps and similar services were so strong already, so convenient, and so deceptively cheap.

I remember similar conversations about Free Software in the 90s, where people were questioning whether the convenience of the proprietary world could ever be challenged. Now the issues of control over your software strategy and the ability to innovate are increasingly becoming commonplace.

Data control wasn’t really a topic for many so far although the two are clearly inseparable. But somehow too much of it sounded like science fiction or bad conspiracy theories.

There have of course been discussions among people who paid attention.

Following the concerns about the United States’ capabilities to monitor most of the world’s transmitted information through ECHELON, many people were alarmed about the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). It has given rise to many conspiracy theories about how the United States have access to virtually all the information hosted with US technology companies anywhere in the world and would be able to use that information to their military, political and economic advantage. But no-one wanted to believe them, as the United States feel so familiar thanks to Hollywood and other cultural exports, and in Europe still thanks to the gratefulness many people still hold for the US contribution to liberating Europe 50 years ago.

Only stories about US surveillance weren’t conspiracy theories, it seems.

There has been a flurry of public reports around a large number of security and privacy relevant issues in the past weeks. But due to the complexity of the issue, most articles only deal with a tiny piece of the puzzle, and often miss the bigger picture that I am seeing right now.

Trying to provide that picture has quickly left me with an article much too long for general reading, so I’ve decided to try and break it up into four articles, of which this is the first. Its goal is to get you up to speed with some of today’s realities, in case you hadn’t been paying attention.

Part I: What We Know

The recent disclosures about the NSA PRISM program have made it quite clear that what is written in black and white in US law is also being put into action. As Caspar Bowden summarized clearly in his presentation at the ORGCon2013, FISA provides agents of the United States with access to “information with respect to a foreign based political organization or foreign territory that relates to the conduct of the foreign affairs of the United States.” It’s limiting factor is the 4th Amendment, which does not apply to people who are not located in the United States. Which is most of us.

In other words: The United States have granted themselves unlimited access to all information they deem relevant to their interests, provided at least one party to that information is not located in the United States.

And they have installed a very effective and largely automated system to get access to that kind of information. Michael Arrington has done a good job at speculating how this system likely works, and his explanation is certainly consistent with the known facts as well as knowledge of how one would design such a system. If true, mining all this information would be as easy and not much slower as any regular Google search query.

What’s more, there is no functioning legal oversight over this system, as the US allow for warrantless wiretapping and access to information. The largest amount of queries most likely never saw a judge while simultaneously being labelled secret. And according to what one has to intepret from the statements of Edward Snowden, only the smallest number of queries ever make it to the secret FISA Court (FISC). A court which is secret itself and has been described as a “rubberstamping court” in many reports.

And we know the United States is far from the only country involved in such activities.

Turns out the United Kingdom has been just as active, and might even have gone to further extremes in their storing, analysis and access of personal information as part of its “Mastering the Internet” activities. It would be naive to assume that is where it stops. We know that other countries have well trained IT specialists working on similar activities, or even offensive measures.

China has been a major target. But it also successfully read the internal documents of German ministries for years, and managed to even breach into Google‘s internal infrastructure. Israel has been known to have some of the best IT security specialists in the world, and countries such as India and Brazil are certainly large enough and with major IT expertise.

Naturally there is not a whole lot of publicly documented evidence, but given that this subject has been discussed for over a decade one would have to assume total ineptitude and incompetence in the rest of the world outside the US and UK to assume these are the only such programs.

The most reasonable working assumption under these circumstances is:

Surveillance is omnipresent and commonly employed by everyone with sufficient ability.

But it’s not just surveillance of readily available data with support from companies that are required by law to comply with such requests.

Offensive Measures

Another way in which countries engage in the digital world is through active intrusion. In Germany there was a large debate around the ‘Federal Trojan‘, which in some ways goes a good step further than PRISM. Such active intrusion damages the integrity of systems, has the potential to leave them damaged, and potentially subject to easier additional break-ins. How easy it is to make use of this kind of technology has become clear during the public FinFisher debate.

The price tag of this kind of tool is easily within reach of any government worldwide, and it would be naïve to assume that countries and their secret agencies do not make use of it.

But in the flurry disclosures another interesting aspect has also been revealed: At least some software vendors are complicit with a number of governments to facilitate break-ins into customer systems. The company that has been highlighted for this behaviour is Microsoft, source of the world’s dominant desktop platform.

Rumours about a door in Microsoft Windows to allow the US government access have been floating around now for a long time, but always been denied. And rightly so, apparently. It is not that Microsoft has deliberately weakened their software in a specific place. They didn’t have to. Instead, they manipulated the process of addressing vulnerabilities in ways to allow the NSA and others to break into 95% of the world’s desktop systems.

But Microsoft is not the only party with knowledge about vulnerabilities in their systems.

So the situation of users would arguably have been better if they had installed a back door as that would limit the exploit to a number of parties that are given access through SSL or other mechanisms. That would have been imperfect, but still better than the current situation: There is no way to know who has knowledge of these vulnerabilities, and what use they made of it.

How that kind of information can be used in addition to the FinFisher type of software has been demonstrated by Stuxnet, the computer worm that was apparently targeted at the Iranian uranium centrifuges and was in fact capable of killing people.

We now live in a world where cyber-weapons can kill.

Just a couple of days ago, the death of Michael Hastings in a car crash in Los Angeles was identified as a possible cyber-weapon assassination. I have no knowledge of whether that is the case, but what I know is that it has become possible. And of course anyone sufficiently capable and motivated is generally capable of creating such a weapon – no manufacturing plants or special materials required.

All of this of course is also known to all the security agencies around the world. So they are trying to increase their detection and defence. But since this is an asymmetrical threat scenario, it is hard to defend against.

PRISM wasn’t motivated by an anti-democratic conspiracy

Too many comments following the PRISM disclosures sounded like there was a worldwide conspiracy involving hundreds of thousands of people, including many heads of states, to undo democracy. And it seems that some people, such as US president Barack Obama, became part of the conspiracy when they came into power.

To me it seems more likely they received more information and became deeply concerned about what would happen if we for instance started seeing large-scale attacks on the cars in a country. To them, PRISM probably looked like an appropriate, measured response. That is not to say I believe it is an effective countermeasure against such threats. And if Edward Snowden is to be believed, it has likely been subverted for other purposes. Considering he threw away his previous life and took substantial personal risk, and reading up on what people such as Caspar Bowden have to say, I have little reason to doubt his credibility.

Given the physical and other security implications of all of the above I guess only very few people would argue that the state has no role in digital technologies. So I think governments should in fact be competent in these matters and ensure that people are safe from harm. That is part of their responsibility, after all. Just banning all the tools would put a country at a severe disadvantage to fulfil that role for its people.

At the same time these tools are extremely powerful and intrusive. So what should governments be allowed to do in this pursuit, and how should they do it? Also, how do we have sufficient control to uphold the principles and liberties of our democratic societies? Also, what does all of this mean for international business and politics?

These will be some questions for the upcoming articles, so stay tuned.

Updates:

- [ Part 2: Totalitarian Clouds ] – Trying to understand the social impact

- [ Part 3: No More Business Secrets] – The business impact

- [ Part 4: Politics and Power Struggles ] – The political side

The Post-PRISM Society: Totalitarian Clouds

After a somewhat brief overview over the world we find ourselves in, the question is what does this mean to us as a society?

As highlighted in the previous article, governments have no realistic option not to engage in some form of activities to protect their people from threats that originate on-line or have an on-line component. These were the grounds for German chancellor Angela Merkel to make statements of support for PRISM. The problem is that I doubt it is effective and adequate to the threat. The side effects seem out of sync with the gain. That this gain is only claimed, not proven due to alleged security concerns, also does nothing to help the case.

It has become public knowledge these technologies exist and make mass surveillance can and is being implemented, and works efficiently. Calling for a general ban is unrealistic, and naive. Of course these technologies will be used against people, businesses and governments by someone – be they states or organisations. So the actual question is: Which are the circumstances under which use of such technology is acceptable?

Looking at the initial reactions, a great number of people – consciously or not – base their reaction on Article 12 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. And considering the consequences, that does not seem very far fetched.

Consequences of the Surveillance Society

There are some stories floating around where people have suffered repercussions such as being denied entry to the United States. But that’s probably the extent of it for many of us unless you are a public figure, or ever find yourself in a job where you would have influence on a decision that might be of major consequence to the United States.

But that’s only the fairly superficial perspective.

Consider for a moment the Arab spring where governments desperately tried to remain in power. In several cases the governments overthrown were the same ones that received strategic and practical support by the United States – including military and secret service activities – as part of their plans for the region. These governments in their desperate attempts to retain control knew which activists to imprison, sometimes torture and often confronted them with their own private messages from Facebook and Twitter.

Could those governments have to obtained that data itself? Possibly. But there is another option.

FISA makes it legal for the United States to obtain and make use of that data for the strategic interests of the United States. And Prism would have made it almost trivial. So the simpler way for those governments to know what was planned would have been to receive dossiers from their US contacts. Does this prove it happened that way? Certainly not. But it demonstrates the level of influence this combination of technical ability is giving the United States and other countries.

“Still,” most people think ‘I am living in a safe country and have no plans to overthrow my government.’

“Nothing to hide, nothing to fear” has been used to justify surveillance for a long time. It’s a simple and wrong answer. Because everyone has areas they would prefer to remain private. If someone has the ability to threaten you with exposing something you do not wish to see exposed, they have power over you. But what’s more: People who have to assume to be watched at all times, even in their most intimate moments and inner thoughts, behave differently.

A culture of surveillance leads to self regulation, with fundamental impact how people behave at all times. Will you still speak up against things you perceive as wrong when you fear there might be repercussions? Or would you perhaps ask yourself whether this particular issue is important enough to risk so much, and hope that it won’t be as bad, or that someone else will take action?

Also, consider the situation of people who absolutely rely upon a certain level of privacy for their professional lives, such as lawyers, journalists and others. That no-one in these professions should be using these services should be self-evident. But if a society adopts the “Nothing to hide, nothing to fear” dogma, those who communicate for good reason with such professions will stand out as dark shadows in an otherwise fully lit room, and will raise suspicion.

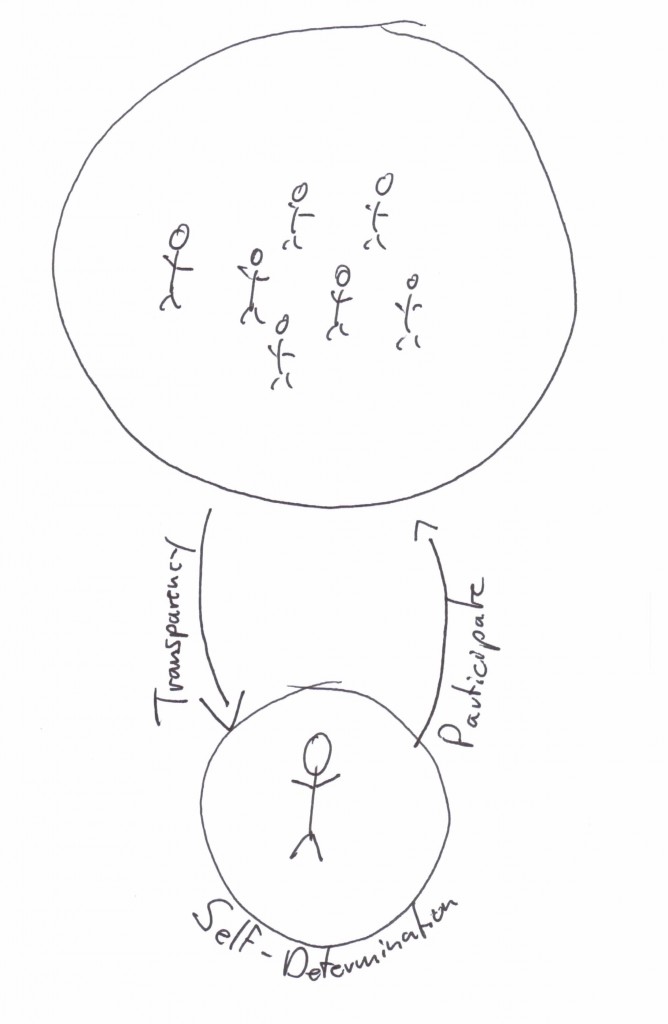

If privacy becomes the exception those who require privacy will easily be singled out. The only way to avoid this is to make privacy the norm: If everyone has privacy, no-one will be suspicious for it.

And there are good reasons you would want to do your part to live in such a society, because the functioning of democracy as a whole is linked to a set of factors, including a working media, ability to form political opinion, and become politically active to achieve change for the better. And even if you yourself have no ambition in this way at this point in time.

Privacy is one of the essential building blocks of a free society.

You might find yourself activated by misspent tax money, a new highway being planned through your back yard, or the plans to re-purpose your favourite city park for a shopping mall. And if it isn’t yourself, perhaps something will make your parents, siblings, spouse, kids, best friend want to take action and then require a society that grants privacy in order not to be intimidated into silence.

So there are good reasons why people worry about this level of surveillance.

Why, then, are they choosing to voluntarily support it?

Feudal Agents of the Totalitarian State

It has been subject of discussion in the software freedom community for some time, but only now appears to hit the radar of a larger subset of the forward thinking IT literates: The large US service providers own users and their data in ways that led security guru Bruce Schneier to comparing them to feudal lords, leaving their users as hapless peasants in a global Game of Thrones power struggle.

Some time ago already, Geek & Poke probably summarized it slightly more pointedly:

One aspect of using these services is that users place themselves under surveillance as part of their payment for the service. The plethora of knowledge Facebook keeps on everyone that is using it, and everyone that is not using it, has been disclosed time and again, last time during the shadow profile exposure. But this has not been the first time. Nor can anyone reasonably expect Google, Microsoft or Apple to behave any different.

What is important to understand is that the centralisation of these services, and turning devices into increasingly dumb data gathering and supply devices is not accidental, nor is it technologically necessary. We all carry around a lot more computing power all the time than was readily available just some years ago.

So these devices and services could operate in a de-centralized and meshed fashion.

But then the companies would not get to profile their users in such detail, potentially gathering every intimate detail about them, such as whether they were aroused when they last used voice search to find the nearest hotel. Or did you think that command was analysed on your smart phone, and not by the (almost) infinitely powerful processing power in the data centres of your service provider?

Data is the new gold, and these companies are mining it as best they can.

Naturally these companies are always downplaying the amount of data collected, or the impact that use of this data might have on individuals. PRISM exposed this carefully crafted fallacy to some extent.

It also raised the question: What is it worse? That the government which can be held accountable to a larger degree gets access to some data gathered by a company? Or that a company that is responsible to no-one but its shareholders gathered all of it?

In fact, cynically speaking, one might even think these companies are mostly unhappy about the fact that the US government wants free, unlimited access to the raw data rather than the paid for refined access they offer as part of their business model.

But the root cause is in the centralised gathering of such data under terms that do not make these companies your service providers, but you their peasant. This treasure trove will always attract desires, and countries have ways to get access because they have ways to impact profits. Now that the PRISM disclosure taught them what’s possible, countries such as Turkey are quickly catching on, demanding access to details of Gezi protesters.

So while these companies are often wrapping themselves in liberty, the internet and all that is good for humankind, by their existence and business model they make a contribution to a totalitarian society.

Whether that contribution is decisive, or outweighs the instances where they do good, I cannot judge.

But using these providers for your services and getting all up in arms about PRISM is somewhat hypocritical, I’m afraid. It’s a bit like complaining about losing your foot when you’ve voluntarily and without need amputated your entire leg before to be able to make use of the special “one-legged all you can eat buffet.”

Choices for Free Citizens

So assuming you want to break free of this surveillance and the tendencies towards a totalitarian society, which are your options?

Firstly, choose Open Source / Free Software and Open Standards. There is a plethora of applications out there and the way in which their internal workings and control structures are transparent and publicly developed makes it much more likely they will not provide back doors to your data. Following the PRISM leaks, sites such as http://prism-break.org have sprung up that try to help you do just that.

Secondly, start making use of encryption, which is easier and more effective than you might think.

Chances are that someone in your circle of friends or family is already using some or even many of these applications. Get them to help you get started yourself.

But assuming you are not a technical person, which is most of society, the most important choice you can likely make is with your feet and wallet by choosing services that work for you and put themselves at your service – rather than services that process you and put you at their service.

The important place for this is to look at the terms of the services you are using.

I know this is tedious, and these terms are often deliberately written to make eyes glaze over when trying to understand what they actually say.

But there is a web site that can help you with it: Terms of Service; Didn’t Read. Check out the services you are currently using, and get yourself the browser extension so you at least start getting an idea of what kinds of rights you are surrendering by making use of the services.

As for providers that offer you the same convenience, but without the mandatory cavity search, there are still quite a few. Naturally it makes sense to look at their terms of services carefully, ensure they are based in a legislation of your choice, and use technologies that you can trust. If you are not sure, ask them to explain what standards they observe with regards your data. And ensure you can switch providers, even switch to self-hosting if you want to, without necessarily changing technologies.

And once you’ve looked through all those criteria and made your homework on which solutions can deliver all of this, without compromise, take control of your data and software.

Disclaimer

I’m not a party without interest in this debate. You can easily inform yourself about what I’ve done in the past in this area. And my past years I’ve dedicated to building a technology that would allow people to own their data and software, while providing all the features users have grown accustomed to.

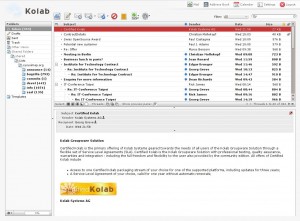

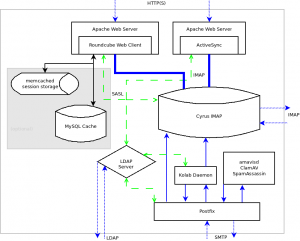

That technology is called Kolab, and of course I’d be delighted if you got in touch with us, or installed Kolab.org on your own, or even made use of the http://MyKolab.com service. Because all of this will help us continue to work to the goal of allowing people secure, powerful collaboration across platforms while owning their own data and software.

But it’s this work that has followed from my analysis, not the other way around.

So make up your own mind.

All articles: