During the last year hell seems to have frozen over: our corporate overlords neighbours at Apple, Google and Facebook have all pushed for crypto in one way or another. For Facebook (WhatsApp) and Google (Allo) the messenger crypto has even been implemented by none less than the famous, endorsed-by-Edward-Snowden anarchist and hacker Moxie Marlinspike! So all is well on the privacy front! … but is it really?

EDIT: A French version of this post is available here. I can’t verify its correctness, but I trust the translators to have done their best and thank them for the effort!

Contents

- Encryption

- Software Freedom and Device Integrity

- (De-)centrality, vendor control and metadata

- Summary (go here if you are lazy)

I have argued some points on mobile messaging security before already and I have also spoken about this in a podcast (in German), but I fealt I needed to write about it again since there is a lot of confusion about what privacy and security actually mean (in general, but especially in the context of messaging) and recent developments give a false sense of security in my opinion.

I will discuss WhatsApp and the Facebook Messenger (both owned by Facebook), Skype (owned by Microsoft), Telegram (?), Signal (Open Whisper Systems), Threema (owned by Threema GmbH), Allo (owned by Google) and some XMPP clients, as well as briefly touching on ToX and Briar. I will not discuss “features” even if privacy related like “message has been read”-notifiers which are obviously bad. I will also not discuss anonymity which is a related subject, but from my point of view less important if dealing with “SMS-replacement apps” as you actually do know your peers anyway.

Encryption

When most people speak of privacy and security of their communication in regard to messaging it is usually about encryption or more precisely the encryption of data in motion, or the protection of your chat message while it is traveling to your peer.

There are basically three ways of doing this:

- no encryption: everyone on your local WiFi or some random sysadmin on the internet backbone can read it

- transport encryption: connections to and from service provider e.g. WhatsApp server and in between service providers are safe, but service provider can read the message

- end-to-end encryption: message is only readable by your peer, but time of communication and participants still known to service provider

Also there is something called perfect forward secrecy which (counter-intuitively) means that past communications cannot be decrypted even if your long-term key is revealed/stolen.

Back in the day most apps including WhatsApp where actually of category 1, but today I expect almost all apps to be at least of category 2. This reduces the chance of large-scale unnoticed eaves-dropping (that is still possible with e-mail for example), but it is obviously not enough, as service providers could be are evil or can be forced to cooperate with potentially evil governments or spy agencies lacking democratic control.

Therefore you really want your messenger to do end-to-end and right now the following all do (sorted by estimated size): WhatsApp, Signal, Threema, XMMP-Clients with GPG/OTR/Omemo (ChatSecure, Conversations, Kontalk).

Messengers that have a special operating mode (“secret chat” or “incognito mode”) providing (3) are Telegram and Google Allo. It is very unfortunate that it is not turned on by default so I wouldn’t recommend them. If you are forced to use one of these, always make sure to select the private mode. It should be noted that Telegram’s end-to-end encryption is viewed as less robust by experts although most experts agree that actual text-recovery attacks are not feasible.

Other popular programs like the Facebook messenger or Skype do not provide end-to-end encryption and should definitely be avoided. It is actually proven that Skype parses your messages so I won’t discuss these two any further.

Software Freedom and device integrity

Ok, so now the data is safe while traveling from you to your friend, but what about before and after it is sent? Can’t you also try to eavesdrop on the phone of the sender or the recipient before it is send / after it is received? Yes, you can and in Germany the government has already actively used “Quellen-Telekommunikationsüberwachung” (communication surveillance at the source) precisely so they can circumvent encryption.

Let us revisit the distinction of (2.) and (3.) above. The main difference between transport encryption and end-to-end is that you don’t have to trust the service provider anymore… WRONG: In almost all cases the entity running the server is the same as the entity providing you with the program so of course you must trust the program to actually do what it claims it does. Or more precisely, there must be social and technical means that provide you with sufficient certainty that the program is trustworthy. Otherwise there is little gained from end-to-end encryption.

Software Freedom

This is where Software Freedom comes into the picture. If the source code is public there are going to be lot’s of hackers and volunteers that check whether the program actually encrypts the content. While even this public scrutiny cannot give you 100% security it is widely recognized as the best process to ensure that a program is generally secure and security problems become known (and then also fixed). Software Freedom also enables unofficial or competing implementations of the Messenger app that are still compatible; so if there are certain things that you don’t like or mistrust about the official app you can chose another one and still chat with your friends.

Some companies like Threema that don’t provide you their source of course claim that it is not required for trust. They say that they had their source code audited by some other company (which they usually paid to do this), but if you don’t trust the original company, why would you trust someone contracted by them? More importantly, how do you know the version checked by the third party actually is the same as the version installed on your phone? [you get updates quite often or not?]

This is also true for governmental or public entities that do these kind of audits. Depending on your threat model or your assumptions about society you might be inclined to trust public institutions more than private institutions (or the other way around), but if you look at e.g. Germany, with the TÜV there is actually one organisation that checks both the trust-worthiness of messenger apps and whether cars produce the correct amount of pollution. And we all know how well that went!

Trust

So when deciding on trusting a party, you need to consider:

- benevolence: the party doesn’t want to compromise your privacy and/or is itself affected

- competence: the party is technically capable of protecting your privacy and identifying/fixing issues

- integrity: the party cannot be bought, bribed or infiltrated by secret services or other malicious third parties

After the Snowden revelations it should be very obvious that the public is the only party that can collectively fulfill these requirements so the public availability of the source code is absolutely crucial. This rules out WhatsApp, Google Allo and Threema.

“Wait a minute… but are there no other ways to check that the data in motion is actually encrypted?” Ah, of course, there are, as Threema will point out, or other people for WhatsApp. But the important part is that the service provider controls the app on your device, so they can listen in before encryption/after decryption or just “steal” your decryption keys. “I don’t believe X would do such a thing” Please keep in mind that even if you trust Facebook or Google (which you shouldn’t), can you trust them to not comply with court orders? If yes, why did you want end-to-end encryption in the first place? “Wouldn’t someone notice?” Hard to say; if they always did this, you might be able to recognize it from analyzing the app. But maybe they do this:

if (suspectList.contains(userID))

sendSecretKeyToServer();

So not everyone is affected and the behaviour is never exhibited in “lab conditions”. Or the generation of your key is manipulated so that it is less random, follows a pattern that is more easily cracked. There are multiple angles to this, most of whom could easily be deployed in a later update or hidden within other features. Note also that being “on the list” is quite easy, current NSA regulations make sure that more than 25,000 people can be added for each “seed” suspect.

In light of this it is very bad that Open Whisper Systems and Moxie Marlinspike (the aforementioned famous author of Signal) publicly praise Facebook and Google, thereby increasing trust in their apps [although it is not bad per se that they helped add the crypto of course]. I am fairly sure they cannot rule out any of the above, because they have not seen the full source code to the apps, nor do they know what future updates will contain — nor would we want to have to rely on them for that matter!

The Signal Messenger

“Ok, I got it. I will use Free and Open Source Software. Like the original Signal.” Now it becomes tricky. While the source code of the Signal client software is free/open/libre it requires other non-free/closed/proprietary components to run. These pieces are not essential to the functionality, but they (a) leak some meta data to Google (more on metadata later) and (b) compromise the integrity of your device.

The last part means that even if a small part of your application is not trustworthy, then the rest isn’t either. This is even more severe for components running with system privileges as they can basically do anything at all with your phone. And it is “especially impossible” to trust non-free components that regularly send/receive data to/from other computers like these google services. Now it is true that these components are already included in most of the Android phones used in the world and it is also true that there are very few devices that actually run entirely free of non-free components, so from my point of view it is not problematic per se to make use of them when available. But to mandate their use means to exclude people who require a higher level of security (even if available!); who use alternative more secure versions of Android like CopperheadOS; or who just happen to have a phone without these Google Services (especially common in developing countries). Ultimately Signal creates a “network effect” that discourages improving the overall trustworthiness of the mobile device, because it punishes users who do so. This undermines many of the promises its authors gives.

To make matters worse: OpenWhisperSystems not only don’t support fully free systems, but have threatened to take legal and technical action to prevent independent developers from offering a modified version of the Signal client app which would work without the non-free Google components and could still interact with other Signal users ([1] [2] [3]). Because of this independent projects like LibreSignal are now stalled. Very much in contrast to their Free Software license, they oppose any clients to the Signal network not distributed by them. In this regard the Signal app is less usable and less trustworthy than e.g. Telegram which encourages independent clients to their servers and has fully free versions.

Just so that there is no wrong impression here: I don’t believe in some kind of conspiracy between Google and Moxie Marlinspike, and I thank him for making their positions clear in a friendly manner (at least in the last statements), but I do think that the aggressive protection of their brand and their insistence on controlling all client software to their network are damaging the overall struggle for trustworthy communication.

(De-)centrality, vendor control and metadata

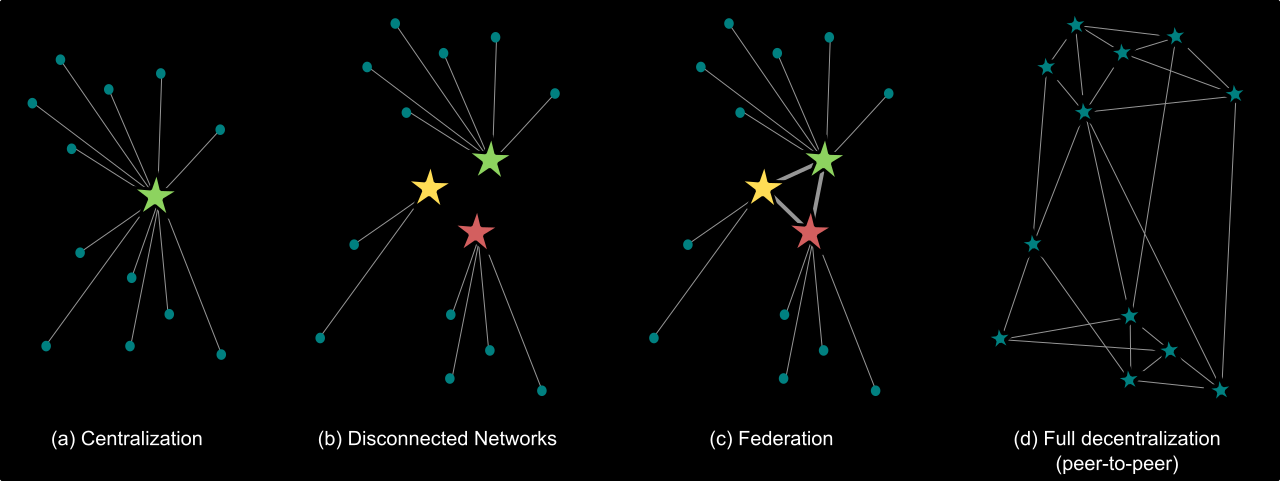

An important part of a communication network is its topology, i.e. they way the network is structured. As can be seen in the picture above there are different approaches that are (more or less) widely used. So while the last section dealt with what is happening on your phone, this one will discuss what is happening on the servers and which role they play. It is important to note that even in centralized networks some communication might still be peer-to-peer (not going through the center), but the distinction is that they require central servers to operate.

Centralized networks

Centralized networks are the most common, i.e. all of the aforementioned apps (WhatsApp, Telegram, Signal, Threema, Allo) are based on centralized networks. While a lot internet services used to be decentral, like E-Mail or the World Wide Web, the last years have seen many centralized services appear. One could for example say that Facebook is a centralized service built on the originally decentralized WWW structure.

Usually centralized networks are part of a bigger brand or product that is marketed together as one solution (in our case to the issue of texting/SMS). For companies selling/offering these solutions it has the advantage that it has full control over the entire system and can change it rather quickly, pushing new functionality to/on all users.

Even if we assume that the service has end-to-end encryption and even if there is a client app that is Free Software, the following problems remain:

- metadata: your messages’ content is encrypted, but the who-when-where information is still readable by the service provider

- denial of service: you may be blocked from using the service by either the service provider or by your government

There is also the more general problem that a privately run centralized service can decide which features to add independently of whether its users actually consider them features or maybe “anti-features”, e.g. telling other users whether you are “online” or not. Some of these could be removed from the app on your phone if it actually is Free Software, but some are tied to centralized structure. I might write more on this in a separate article some time.

Metadata

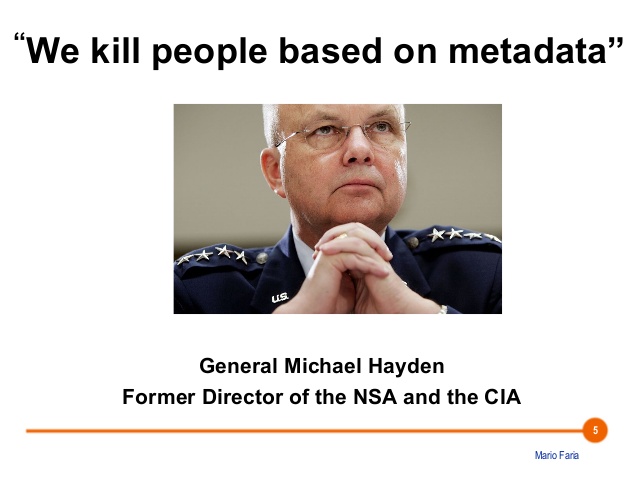

As explained above, metadata is all data, that is not the content of your message. You might think that this data is unimportant data, but recent studies show that the opposite is true. Metadata includes: when you are “online” / if your phone has internet; the time of your messages and who you are texting with; a rough estimate on the length of the messages; your IP-address which can reveal rather accurately where you currently are (at work, or at home, out of town et cetera); possibly also security related information about your device (which operating system, which phone model…). This information has a lot of privacy threatening value and the US secret services actually use it to justify targeted killings (see above)!!

The amount of metadata a centralized service sees depends on the exact implementation, e.g. the “group chat” feature in Signal and supposedly also Threema is client-based so in theory the server knows nothing about the groups. On the other hand the server has timestamps from your communication and can likely correlate these. Again it is important to note that while your service provider may not log this information by default (some information must be retained, some could be deleted immediately), it might be forced to log more data by secret agencies. Signal (as mentioned before) only works in conjunction with some non-free components from Google or Apple who then always get some of your metadata, including your IP-address (and thus physical position) and the time you receive messages.

More information on metadata here and here.

Denial of service

Another major drawback of centralized services, is that they can decide not to serve you at all if they don’t want to or are obliged not to by law. Since many of the services require your phone number to register and they operate from the US, they might deny you service if you are a Cuban for example. This is especially important since we are dealing with encryption that is highly regulated in the US.

As part of Anti-Terrorism measures Germany has just introduced a new law that requires registering your ID when getting a SIM card, even prepaid. While I don’t think that it is likely, it does open the possibility for black-listing people and pressuring companies to exclude them from service.

Instead of working with the companies, a malicious government can of course also target the service directly. Operating from a few central servers makes the infrastructure much more vulnerable to being blocked nationwide. This has been reported for Signal and Telegram in China.

Disconnected Networks

When the server source code of a service provider is Free and Open Source software, you can setup your own service if you distrust the provider. This seems like a big advantage and is argued by Moxie Marlinspike as such:

Where as before you could switch hosts, or even decide to run your own server, now users are simply switching entire networks. […] If a centralized provider with an open source infrastructure ever makes horrible changes, those that disagree have the software they need to run their own alternative instead.

And of course this is better than not having the possibility to roll your own, but the inherent value of a “social” network comes from the people who use it and it is not easy to switch if you loose the connection to your friends. This is why alternatives to Facebook have such a hard time. Even if they were better in every aspect, they just don’t have your friends.

Yes, it is easier for mobile apps that identify people via phone number, because it means you at least quickly find your friends on a new network, but for every non-technical person it is really confusing to keep 5 different apps around just so that they can keep in touch with most of their friends so switching networks should always be the ultima ratio.

Note that while OpenWhisperSystems claim that they are of this category, in reality they only publish parts of the Signal server source code so you are not able setup a server that has the same functionality (more precisely the telephoning part is missing).

Federation

Federation is a concept which solves the aforementioned problem by having the service providers speak with each other, as well. So you can change the provider and possibly the app you are using, but you will still be able to communicate with people registered on the old server. E-Mail is a typical example of a federated system: it doesn’t matter whether you are tom@gmail.com or jane@yahoo.com or even linda@server-in-my-basement.com, all people are able to reach all other people. Imagine how ridiculous it would be, if you could only reach people on your own provider!?

The drawback from a developer’s and/or company’s perspective is that you have to publicly define the communication protocols and that because the standardization process can be complicated and lengthy you are less flexible in changing the whole system. I do concur that it makes it more difficult for good features to quickly be available for most people, but as mentioned previously, I think that from a privacy and security point of view it is clearly a feature, because it involves more people and weakens the possibility of the provider pushing unwanted features on the users; and most importantly because there is no more lock-in-effect. As a bonus these kind of networks quickly produce different software implementations, both for the software running at the end-user and for the software running on the servers. This makes the system more robust against attacks and ensures that weaknesses/bugs in one piece of software don’t effect the entire system.

And, of course, as previously mentioned, the metadata is spread between different providers (which makes it harder to track all users at once) and you get to choose which of them gets yours or whether you want to operate your own. Plus, it becomes very difficult to block all providers, and you could switch in case one discriminates against you (see “Denial of Service” above).

As a sidenote: It should be mentioned that federation does imply that some metadata will be seen by, both, your service provider and your peer’s service provider. In the case of e-mail this is quite a lot, but this is not required by federation per se, i.e. a well designed federated system could avoid sharing almost all metadata in-between two service providers — other than the fact that there is a user account with a certain ID on that server.

So, is there such a system for instant messaging / texting? Yes, there is, it is called XMPP. While originally not containing strong encryption, there is now encryption that provides the same level as security as the Signal Protocol. There are also great mobile apps for Android (“Conversations”) and iOS (“ChatSecure”) and every other platform in the world, as well.

The drawback? Like e-mail, you need to setup an account somewhere and there is no automatic association with telephone numbers so you need not only convince your friends to use this fancy new program, but also manually find out which provider and username they have chosen. The independence of the phone number system might be seen as a feature by some, but as a replacement for SMS this seems unfit.

The solution: Kontalk, a messenger based on XMPP that still does automatic contact discovery via phone numbers from your address book. Unfortunately it is not yet as mature as other mentioned applications, i.e. it currently still lacks group chats and there is no support for iOS. But Kontalk does prove that it is viable to have the same features built on XMPP that you have come to expect from applications like WhatsApp or Telegram. So from my point of view it is only a matter of time until these federated solutions are on feature parity and similar in usability. Some agree with this point of view, some don’t.

Peer-to-Peer networks

Peer-to-peer networks completely eliminate the server and thereby all metadata at centralized locations. This kind of network is unbeatable from a privacy and freedom perspective and it is also almost impossible to block by an authority. An example of a peer-to-peer application is ToX, another one is Ricochet (edit: not for mobile) and there is still under development Briar which also adds anonymity so even your peer doesn’t know your IP address. Unfortunately there are principle issues on mobile devices making it hard to maintain the many connections required for these networks. Additionally it seems impossible right now to do a phone-number to user mapping so there can be no automatic contact discovery.

While I don’t currently see the possibility of these kind of apps stealing market share from WhatsApp, there are use cases, especially when you are being actively targeted by surveillance and/or you have group of people who collectively decide to move to such an app for their communication, e.g. political organisations.

Summary

- Privacy is getting more and more attention and people are actively looking to protect themselves better.

- It can be considered positive that major software providers feel they have to react to this, adding encryption to their software; and who knows, maybe it does make life for the NSA a little bit harder.

- However there is no reason that we should trust them anymore than we have previously, as there is no way for us to know what their apps actually do, and there remain many ways they can spy on us.

- If you are currently using WhatsApp, Skype, Threema or Allo and expect a similar experience you might consider switching to Telegram or Signal. They are better than the previously mentioned (in different ways), but they are far from perfect, as I have shown. We need federation in the medium to long-term.

- Even if they seem to be nice people and very skilled hackers, we cannot trust OpenWhisperSystems to deliver us from surveillance as they are blind to certain issues and not very open to cooperation with the community.

- Some cool things are cooking in XMPP-land, keep an eye out for Conversations, ChatSecure and Kontalk. If you can, support them with coding skills, donations or friendly e-mails.

- If you want a zero-metadata approach and/or anonymity, try out ToX or wait for Briar.