Wu Ming 1, author

29 October 2018, Italy

“How A Conspiracy Theory Is Born And How To Deal With It, Part One” can be found here.

The original article in Italian was published online at the following link: https://www.internazionale.it/reportage/wu-ming-1/2018/10/29/teoria-complotto.

V0.2. Translated by Joseph P. De Veaugh-Geiss (contact: tds [at] systemli.org) in December 2020 with permission from both the author and the weekly magazine Internazionale. For more details about the translation, see part one of this article.

QAnon at the White House

On 31 July 2018, an enthusiastic crowd greeted Trump in Tampa, Florida, wearing QAnon T-shirts and raising signs saying “We are Q”. They stole the scene from the president, with reporters talking almost exclusively about them. It was QAnon’s definitive entry into national and, shortly thereafter, international news. On 8chan, Q commented: “Welcome to the mainstream. We knew this day would come.”

Whereas before Tampa the president may have winked at the “bakers” by writing “17” in a couple of tweets, now he is toying with the conspiracy in a transparent way. On 24 August 2018, Trump received Lionel Lebron, a 60-year-old radio host and QAnon apostle, in the oval office. Lebron immediately published a photo in which he appears, gloating, posing with his hero.

In practice, Trump welcomed to the White House a man who has accused two of his predecessors – Obama and Clinton – of leading a satanic sect of pedophiles. The accusation was extended to the entire opposition party and some Republicans, such as Senator John McCain, who was dying in those very hours.

The episode sums up the bizarreness of the whole affair. Usually a conspiracy is against the powers that be. The position of the plotter is to denounce evil and the hypocrisy of power. In the conspiracy genre, it is rare for the hero to actually be the head of government – let alone the most powerful politician on Earth. But QAnon claims just that. “This time, the heroes are already in charge”, wrote Molly Roberts in the Washington Post, “and, still, the theorists see themselves as victims. Why, even with their man in the Oval Office, do they feel embattled?”

In the New York Times, Michelle Goldberg gave an answer: QAnon serves to reduce “the cognitive dissonance caused by the gap between Trump as his faithful followers like to imagine him, and Trump as he is. […] You don’t create a wild fantasy about your leader being a covert genius unless you understand that to most people, he looks like something quite different. You don’t need an occult story about how your side is secretly winning if it’s actually winning.”

The white middle class who voted for Trump had huge expectations. Expectations of revenge, or rather, catharsis. Trump encouraged these expectations in every way, but now in 2018 we are halfway through Trump’s first term and there has been no revival or rebirth. Worse, there hasn’t even been an improvement: no measures have been introduced to curb the impoverishment of the middle class.

The obvious conclusion would be: Trump is doing nothing for his constituents. But admitting that would be admitting you had deluded yourself, you had believed the lies: security, immigrants, the wall at the Mexican border… Believing in QAnon helps one not feel betrayed and cheated: although it may seem that Trump is not doing anything for his voters, he is in fact fighting a secret battle against pedophiles who rule the world.

The nationalism of Trump’s voters shouting “Make America great again!” is irreconcilable with the scenarios of the Mueller investigation. The president being investigated for aid that he received from Putin’s Russia? Unimaginable. QAnon solves this dilemma as well: by arguing that Mueller’s task is not to investigate Trump but rather to strike at a ring of pedophile Satanists, the QAnon followers restore the patriotic aura of the president.

Genius, champion of freedom, defender of children, savior of America and the world … how could Trump not feel flattered? Perhaps that is why he never distances himself from the conspiracy; on the contrary, he welcomes it.

By now curiosity about QAnon is skyrocketing and articles are coming out all over the world. Every line written on 8chan and Reddit ends up under scrutiny, and a vicious circle is repeated, the one typical of the relationship between mainstream journalism and conspiracy theorists. Paul Musgrave pointed it out in the Washington Post: “QAnon and related phenomena are vastly magnified by the media. Over the past few years, […] we’ve learned a lot about how Internet communities can manipulate public attention and the media into appearing larger and more powerful than they are.”

In The Guardian, Whitney Phillips said: “[M]any journalistic responses to trollish media manipulation tactics have remained constant. What this coverage has always done is incentivize precisely the behaviors it purports to condemn. In the process, it ensures that the same tactics will be used in the future – because the tactics are proven to work.”

Some of those same tactics, however, have also been proven effective in dismantling conspiracy theories and defusing moral panic. It happened in Italy with satanic ritual abuse. Perhaps useful lessons can be drawn from that story.

Luther Blissett Project

In late spring 2018, the Wu Ming collective received this message: “Apparently, someone took Luther Blissett’s old strategic playbook and made it an alt-right conspiracy theory”. Below the message was a link to an article in Vice dedicated to QAnon. The sender is an old friend, Florian Cramer, professor for visual culture at Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam, Holland. Shortly afterwards, others write us: the story of QAnon sounds familiar to them. But what is Luther Blissett’s “playbook”? And what does it have to do with QAnon?

To answer this question, we must go back to 1994. At that time, hundreds of activists, artists, and cultural agitators had adopted the pseudonym Luther Blissett to sign works, performances, and actions of various kinds. It was a live role-playing game, and it would last five years. It consisted in creating the reputation of an imaginary provocateur, a mythical character halfway between the “social bandit” and the “trickster“. For reasons that would never be clarified, we had chosen the name of a former English footballer, who passed through Milan for one season, in 1983-1984, just before the Berlusconi era.

While Luther Blissett was active in several countries, the phenomenon mainly took root in Italy, where a network of collectives operated, the Luther Blissett Project (LBP), whose main hubs were in Bologna and Rome. In a short amount of time, the LBP became known for some very elaborate pranks against the media.

In December 1994 a crew from the television program Chi l’ha visto? (‘Who’s seen them?’) was searching between Friuli Venezia Giulia and the United Kingdom for the English magician Harry Kipper, who went missing while cycling around Europe tracing the word ART on the map. He disappeared along the vertical line of the T, at the border between Italy and Slovenia. An intriguing story, but false in every detail, because Kipper never existed.

In 1998 the art world became passionate about the artistic works and biography of Darko Maver, a Serbian artist invented from scratch, who Blissett faked the death of in a prison in Podgorica, under NATO air raids.

These are just two examples, among many. Each time Blissett explained, after the fact, which problems in the media and which cultural mechanisms they exploited to spread the fake news.

The moment of explanation is always the most important part. The pranks aim to draw attention to sensitive issues and the ways in which journalists and pundits talk about them. For this reason, when there was growing moral panic in Italy about pedophilia and satanism, the LBP asked: how do we quell it?

One of the first steps was to get Satan’s Silence: Ritual Abuse and the Making of a Modern American Witch Hunt, a book by Debbie Nathan and Michael Snedeker published in the United States in 1995. The authors reconstructed the history of satanic ritual abuse (SRA), and they denounced recovered-memory therapy (RMT), having surveyed several cases of false memory and providing evidence to reopen several investigations.

In January 1996, the arrest of the Bambini di Satana (‘Children of Satan’) was an opportunity to act.

The tarantella dance of the Satanists

Blissett planned a series of pranks to show how easy it is to induce moral panic in public opinion, and to draw attention to the collective counter-investigation I Carlini di Satana, which was published in the Bologna-based periodical Zero in Condotta (ZiC). Every week, beginning in September 1996, Blissett would expose the contradictions of the prosecution, criticize the argumentation, and show the dynamics of vilification in the press.

The most complex prank – actually a series of pranks – took place in the city Viterbo. It had begun in February 1996, but responsibility for the prank would only be claimed by LBP in March of the following year.

If one read the newspapers in those months, Viterbo seemed besieged by evil, and the surrounding forests overcrowded with Satanists. The newspapers published several reports from a group of anonymous Catholic-fascist vigilantes – il Comitato per la Salvaguardia della Morale (CoSaMo) (‘the Committee for the Safeguarding of Morals’) – who were committed to stopping black masses and beating the Satanists with sticks. None of this existed: Blissett had passed off rumors, fake news, and blurred images to newspapers, material that was accepted and published without any verification.

After a year, the Satanists in Viterbo moved from the local papers to the national ones. On 8 February 1997, Studio Aperto, the news program of Italia 1, transmitted a video from CoSaMo. It was a ritual, filmed in secret. The scene was lit by candlelight, barely showing the outlines of hooded characters, who were bent over their knees and performing strange chants. A girl could be heard screaming … then the filming was interrupted.

Blissett sent the complete sequence to RAI, which aired it on 2 March during the weekly news program TV7. In the scenes not sent to Studio Aperto, the hooded characters got up, someone started the traditional tarantella folk dance, and everyone, including the girl, would start dancing. In the newspaper la Repubblica, Loredana Lipperini wrote an account of the entire prank.

In the meantime, a less complex but very effective prank took place in Bologna at the expense of the local paper Il Resto del Carlino.

On 2 August 1996 the reporter Biagio Marsiglia had returned from vacation. In the editorial office, he found an envelope addressed to him which had arrived several weeks earlier. Inside there was a receipt for a luggage deposit, accompanied by a message: “Pick the bag up at the station. It concerns the Bambini di Satana. Important” (“Ritira la borsa alla stazione. Riguarda i Bambini di Satana. Importante”).

Marsiglia rushed to the station. To collect the bag, which had been there for a month, he had to pay 295,000 Lire [roughly 150 Euro]. When he opened it, his jaw hit the floor. It contained a skull, other human bones, and two sheets of paper: a message from CoSaMo, known at the time in the town of Viterbo but not in Bologna, and a photocopy of an article from the local paper Corriere di Viterbo entitled “Hunters of Satan”.

The message says:

“Exhibition: skull and human bones swiped during the famous ritual before their arrival. It was supposed to be used for the child. There are more things between the Apennines and the lowlands than in your papers. There is also a trail in Viterbo. We hereby inform the public of our presence in the city […]”. (“Reperto: teschio e ossa umane trafugati durante il famoso rito prima del loro arrivo. Doveva essere usato per il bambino. Più cose tra l’Appennino e la bassa di quante ne contengano le tue cronache. C’è anche una pista viterbese. Con la presente avvisiamo il pubblico della nostra presenza in città […].”)

In Il Resto del Carlino the day after, there was an an article, with color photos of the findings, under the title: “The ‘Hunters of Satan’ enter the scene. A mysterious committee presents Carlino with a skull, bones, and letters. The grim package was placed in a backpack. Are these remains stolen from the sect of Marco Dimitri?” (“Entrano in scena i ‘cacciatori di Satana’ . Un misterioso comitato fa ritrovare al Carlino un teschio, ossa e lettere. Il lugubre fardello era sistemato in uno zainetto. Si tratta di resti sottratti alla setta di Marco Dimitri?”).

While the reporter was on vacation, however, the Luther Blissett Project had already taken responsibility for the prank with a “preemptive claim”. It was published in ZiC on 12 July with the title “Un teschio per il Carlino” (‘A skull for il Carlino‘), and it detailed, in advance, what would happen. It’s the principle of the prediction sealed in an envelope, often used by magicians, and it would prove that the story was a prank. The skull and bones were authentic, but they were more than a hundred years old and had come from a closet at the Università di Bologna. A press release had anticipated the foolishness of il Carlino and announced the beginning of a series of updates. Curious about the prank, several journalists were now in touch. Blissett gave them photocopies of Satan’s Silence and other materials.

Il Carlino acted as if nothing had happened – they insisted on sensationalism, and continued to treat the defendants as guilty – but two other newspapers, la Repubblica and Mattina, a local supplement of L’Unità, took a more skeptical line. Doubts about the accusations against the Bambini di Satana came from the art world: writers like Carlo Lucarelli and Enrico Brizzi took a stand. The squats and local social centers received the Bambini di Satana in their 2001 city coordination, a surprising move.

After the prank, the climate around the trial would change: the defendants were no longer ‘monsters’ and their lawyers could work under less public pressure. The prosecution eventually fell apart. The Bambini di Satana would end up being acquitted.

In the fall of 1997, Luther Blissett’s booklet on the case was published, Lasciate che i bimbi. “Pedofilia”, un pretesto per la caccia alle streghe (‘Let the children… “Pedophilia”, a pretext for a witch hunt’). Lucia Musti, prosecutor at the trial, read it and noted that the group showed “incivility in the form of expression and an abuse of the right to criticize” (“inciviltà della forma espressiva e abuso del diritto di critica“). She considered herself to be slandered by characterizations such as a “person thirsty for prominence and wanting to be in the limelight” (“personaggio assetato di protagonismo e luci della ribalta“), and she filed a civil lawsuit. Her demands? Withdrawal of the booklet from bookstores and the destruction of all existing copies, along with one billion Lire (roughly 500 thousand Euro) as compensation for moral and material damages. The summons can be read in the 3rd issue of Luther Blissett’s Quaderni Rossi magazine (January 1999), dedicated entirely to the judicial case.

Musti’s legal action started a long entanglement in the campaign for the Bambini di Satana. This prevented the Luther Blissett Project from also intervening in the case of the “devils” of Lower Modena, with which it had just begun to become active.

The court accepted Musti’s requests, albeit reducing the fine to 80 million lire (roughly 40,000 Euro). However, the sentence came after the publisher’s bankruptcy and at the end of the booklet’s circulation. There were no copies to seize; there was no money for compensation. The signatory of the contract for the Luther Blissett Project was among those convicted. Many years later, that same signatory would write the text you are reading now.

The Eye of Carafa in Trump’s America

In March 1999 the historical fiction Q was published, written by four members of the Bologna-based Luther Blisset Project, all veterans of the counter-campaign on satanic ritual abuse.

Q takes place between 1517, the year in which Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the door of Wittenberg Cathedral, and 1555, the year of the “Peace of Augsburg“, which would put an end to thirty years of religious wars. The novel recounts a long-distance duel between a subversive heretic who goes by many names and a secret agent for the Roman Catholic Church, the latter of which infiltrates the radical movements at the time and distributes fake news by sending messages signed with the biblical name Qoèlet (in Hebrew, the “gatherer”).

Qoèlet alludes to his proximity to power, to the valuable information he can access: “I have already shown you how my ears might help you, given their proximity to certain doors behind which intrigues lurk,” he writes to the preacher Thomas Müntzer, spiritual leader of the peasant insurrection that broke out in Swabia in 1524.

Qoèlet’s missives convince insurgents to gather in Frankenhausen, Thuringia, where they fall into a deadly trap. Although the revolt is defeated, others follow: the novel’s many-named protagonist takes part, but Qoèlet is there to sabotage the insurgents – and to report to his superior in dispatches signed Q.

Q’s boss is Archbishop Gian Pietro Carafa, who in the course of the narrative first becomes a cardinal, then head of the Roman Inquisition, and finally pope under the name Paul IV. Q’s career follows his boss’s: after one last mission in northern Europe, the most dangerous yet, the secret agent is called back to Italy, closer to power but now in a remote position. “In the fresco I’m one of the figures in the background”, he writes in the first line of his diary. The year is 1545. Italy will be the place of the final confrontation between the two adversaries.

After five years of activity with the Luther Blissett Project, as the authors were forming the Wu Ming collective, Q was translated and published in almost all of Europe, in a good part of Latin America, in Russia, Turkey, Japan, South Korea – and, in 2004, in the United States. The book would be appreciated in some niche groups in the U.S., but it remained obscure – which is why American journalists, following the crumbs of QAnon, would be slow to make the connection.

Not only are the similarities between the Q of the novel and the Q of 4chan evident, but there is a strong echo between QAnon and Luther Blissett’s mockery of Satanism. If these are coincidences, they are many and they leave a strong impression.

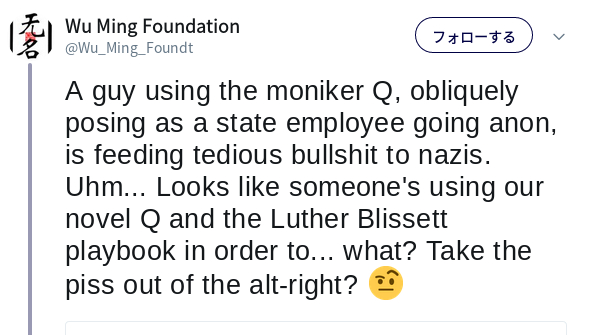

As QAnon took off, we started doing some research and writing short comments on Twitter. The first one is dated 12 June 2018, in which we speculated on something which we would later reiterate in interviews and conferences: perhaps whoever created QAnon had had our novel and our pranks in mind, and merely wanted to make fun of the credulousness of Trump’s supporters. Soon after, though, the prank had gotten out of hand and had taken on a life of its own – with the results we all see. It had gone too far in the wrong direction and responsibility for the prank could no longer be claimed: who would want to admit to having started, out of foolishness, a fascist role-playing game which unleashed armed madmen?

Looks like someone’s using our novel Q and the Luther Blissett playbook in order to… what?

If QAnon really started as a joke, it took the same path as “The Plan” conceived by Belbo, Diotallevi, and Casaubon, protagonists of a novel published in October 1988. Umberto Eco wrote it. It is called Foucault’s Pendulum.

“Do not advance the action according to a plan” – Q

The story told in Foucault’s Pendulum begins in 1970 and ends almost twenty years later. It revolves around two publishing firms in Milan: the respectable Garamond, which publishes university texts and manuals, and the unscrupulous Manuzio, a vanity publisher which prints books for payment and practices real exploitation to the detriment of authors. The two brands could not seem more distant, but ownership is the same – in fact, it is a single publishing house.

After a period of active political engagement, Italy is in full “relapse” in the 1980s. Many who enthusiastically had waved Mao’s Little Red Book are now instead interested in spirituality, esoteric philosophies, and the New Age. Milan is teeming with psychotherapist-gurus, self-styled alchemists, Rosicrucian groups, and so on. It’s an attractive market to exploit, and one day the three editors of Garamond are given the task of finding titles for two book series dedicated to occultism, esotericism, and conspiracy: one, Isis Unveiled, to attract vanity authors; the other, Hermetica, for a more ‘scientific’ approach.

Belbo, Diotallevi, and Casaubon are buried in junk literature. They have to confront an abundance of manuscripts that regurgitate the well-worn, paranoid theories about the Templars, the Rosicrucians, the Freemasons, and the Jews. In the jargon of the publishing house, the authors of those texts are referred to as “the Diabolicals”.

Out of boredom and frustration, the three decide to play a game, or rather, an experiment: to imitate the fallacious logic of the Diabolicals and intertwine all existing conspiracy theories into one which explains the entire history of the world. It is the birth of “The Plan”.

Only they get caught up in the game until they are lost in the labyrinth. And worse happens: in a chain reaction of misunderstandings, The Plan becomes true. Or rather, it is believed to be true in Diabolical circles, with tragic consequences.

The novel begins in medias res. Casaubon, the narrator, reconstructs the descent into the abyss, as the critical intentions of the prank were lost and irony was giving way to something else. “When we traded the results of our fantasies,” he recalls, “it seemed to us – and rightly – that we had proceeded by unwarranted associations, by shortcuts so extraordinary that, if anyone had accused us of really believing them, we would have been ashamed. We consoled ourselves with the realization – unspoken, now, respecting the etiquette of irony – that we were parodying the logic of our Diabolicals. But […] our brains grew accustomed to connecting, connecting, connecting everything with everything else […]. I believe that you can reach the point where there is no longer any difference between developing the habit of pretending to believe and developing the habit of believing.”

Foucault’s Pendulum is not a parody of conspiracy, but an apologue on how vain and counterproductive it is to attempt the path of parody. Satire on these topics can bring those who are already skeptical to laughter, but for those who see conspiracies everywhere there are no “excessive” interpretations – there is almost nothing that cannot be believed.

Untangling the knots of QAnon is also a way to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Echo’s novel.

“A leftist prank”

After Tampa, journalists following QAnon noticed Wu Ming’s tweets. On 6 August 2018, Buzzfeed published an article entitled “It’s Looking Extremely Likely That QAnon Is A Leftist Prank On Trump Supporters”, which included statements from us – here is the full version of the interview – and the article ended up going viral. The similarities with Luther Blissett’s Q and the hypothesis that it was a prank opened up a new line of investigation, and in a short time interviews and articles about QAnon as a “leftist” or “anarchist prank” spread in several languages.

This hypothesis was written about in Artnet, Quartz, Spin, Motherboard, Alternet, Süddeutsche Zeitung, L’Humanité, la Repubblica, Telepolis, and other media. Wu Ming interviewed Henry Jenkins, perhaps the most important scholar on pop culture and digital communities. A post on Artnet’s Facebook page stated: “The history of ‘Luther Blissett,’ the Italian media jamming movement, is suddenly relevant to the US political discussion.”

The word prank had been used, and it changed the semantic framing within which QAnon was being analyzed. Even the traditional right, which until then had wavered or looked down on the conspiracy, decisively distanced itself from QAnon. On the conservative website The Federalist, Georgi Boorman wrote:

“Q mythology is extremely hyperbolic, easily surpassing what in more humorous contexts would be considered satire (which is why some have suggested Q is not a right-winger at all, but a leftist trolling the right).”

Some Trumpist forums, like the sub-reddit r/The_Donald, got the message, and references to QAnon in discussions were verboten, with the complaint that this story was making them look like “a bunch of idiots”. A bunch which, evidently, included “The Donald” himself, who after a few days received Lionel Lebron in the oval office.

Real and imaginary plots

Those who criticize conspiracy theories often come to maintain, in an overreaction, that conspiracies do not exist tout court, resulting in the minimization of all accusations – opening the gates to those who call any uncomfortable investigation or manifestation of critical thinking a “conspiracy”.

Plots have always existed, they exist now, and they will exist in the future. A conspiracy simply consists of several people who agree in secret to plot against someone else. In criminal law there exists “criminal association“, which is a crime of conspiracy.

However, here we will talk about a specific type of conspiracy: that which is political or criminal-political. How does one recognize the real ones?

Usually true political conspiracies have the following characteristics: (a) they have a precise purpose; (b) they involve a limited number of actors; (c) they are realized in an imperfect way, because reality is imperfect; (d) they end up being discovered and reported, usually after a rather short period of time, even if the effects may persist for a long time afterward; and (e) they are part of, and inseparably linked to, a historical context.

Fitting this description is Watergate, a political conspiracy par excellence, which has provided a suffix to the many political conspiracies following it: Irangate, Gamergate, Pizzagate, Pedogate, a very long list.

This conspiracy (a) had a precise purpose, namely spying on Richard Nixon’s enemies and sabotaging his enemies’ activities; (b) it involved a small circle of Nixon’s collaborators – passed into history as the “Watergate Seven” – and a covert unit of spoilers nicknamed the “Plumbers“, dedicated to so-called ratfucking (fucking the rats, that is creating problems for the Democrats); (c) it was implemented in a confusing and clumsy manner, so much so that the plumbers were caught hiding microphones in the Democratic Party headquarters at the Watergate Hotel in Washington; (d) it was discovered and investigated after just over a year, in June 1972, and although Nixon did not resign until 1974, ratfucking ceased immediately; and, finally, (e) it defined an era of American history – to remember Watergate is to remember the United States of the 1970s.

If we remain in 1970s but look to Italy, we see that the main political conspiracies of the time were carried out, with many flaws and imperfections, by a considerable but nonetheless limited number of people who were later identified, investigated, and often tried in court. Terrorists, infiltrators, secret agents, fixers, Freemasons … we know the first and last names of almost all of them.

Although we all too often fixate on the past “mysteries” rather than the facts which have accumulated over the years, in the end we know a great deal about these conspiracies. Many were investigated and denounced in real time: the plot to blame the anarchists for the Piazza Fontana massacre was understood and condemned in the counter-investigation La Strage di Stato (‘The Massacre of the State’) almost immediately.

The strategia della tensione (‘strategy of tension’) lasted about fifteen years and ended with the historical period it was a part of. Its aims – anti-communist, anti-union, reactionary – were identified with good approximation. Many of those responsible would never be charged, but the historical truth is largely out there.

Conspiracy theorists, on the other hand, invert every characteristic of real criminal conspiracies. Here the conspiracies (a) have the widest imaginable purpose, namely to dominate, conquer, or destroy the world; (b) they involve a potentially unlimited number of actors, which can grow with every account, since anyone who denies the existence of a conspiracy is immediately denounced as an accomplice; (c) their alleged unfolding is very consistent, perfect – everything is carried out according to plan, including the smallest of details; (d) they persist even after being described and denounced in countless books, articles, and documentaries; and, finally, (e) they last indefinitely – some have been going on for decades, even centuries. The Templar conspiracy, according to those who believe in it, has been going on for eight hundred years, transcending every era and historical context.

But dismantling conspiracy theories is easy – it is enough to isolate its characteristics. The difficult thing is to convince those who believe in them not to believe them anymore.

What is wrong with debunking?

Debunking is the rational dismantling of a hoax or prank – terms that indicate a conspiracy, fake news story, urban legend, pseudo-scientific doctrine, or scam based on paranormal activity. Debunking is practiced by journalists, bloggers, and associations dedicated to scientific skepticism, such as Comitato Italiano per il Controllo delle Affermazioni sulle Pseudoscienze (CICAP) (‘Italian Committee for the Investigation of Claims of the Pseudosciences’).

For a few years now a lot of attention has been given to debunking – more and more people practice it and courses are held on the topic – and yet conspiracy theories which have have already been debunked continue to circulate, while new ones are born and they spread rapidly. Why?

Conspiracy theorists work with amazement, fascination, and unusual points of view. In doing so, they tap into and satisfy authentic needs: we need surprise in our lives, we need wonder and new angles from which to look at the world and feel different. Conspiracy theorists provide all of this, while making their followers feel special. It is no coincidence that they use the “red pill” metaphor from the movie Matrix: taking the red pill means discovering the truth about the conspiracy, finally revealing the hidden grid of reality.

On the contrary, debunkers often have the air of a party pooper, of someone letting the air out of the balloon. All the more so if they strut in with a political, journalistic, or academic authority, and treat their interlocutors as fools.

The scientific publicist Andrea Capocci, regarding the debate in Italy on vaccines, spoke about a “muscular and technocratic approach” (“approccio muscolare e tecnocratico“) to debunking, an attitude which “the media likes but in the end changes nothing” (“piace molto ai media ma non sposta nulla“). The debunker’s frontal attack on their interlocutor may sparkle and make a good show, especially if peppered with epithets such as “ignorant” or “mule” – but instead of convincing anyone, the attack only generates resentment. The interlocutor doubles down on their position, they feel “alternative”; the debunker comes across as a defender of the status quo, which results in the exact opposite of what they wanted.

The paradox is that conspiracy theories may, in fact, be upholding the status quo. In April 2018 the scientific journal Political Psychology published a study entitled Blaming a Few Bad Apples to Save a Threatened Barrel: The System-Justifying Function of Conspiracy Theories. The authors explain that conspiracy theories, even if “represented as subversive alternatives to establishment narratives”, actually “may bolster, rather than undermine, support for the social status quo when its legitimacy is under threat”. Those who believe conspiracy theories tend to accuse small groups of villains, instead of seeking larger systemic causes to problems. “By blaming tragedies, disasters, and social problems on the actions of a malign few, conspiracy theories can divert attention from the inherent limitations of social systems.”

We could call conspiracy theories “deflecting narratives”. The conspiracy starts with real problems, but it offers distorted interpretations of them, exaggerates details, and picks out scapegoats – thus deflecting attention from the hard work of actually solving the issues.

To use an electrician’s metaphor, conspiracy is the “grounding” of capitalism: it disperses energy downwards and prevents people from being “electrocuted” by the awareness that the system is not working.

Climate disaster, as Naomi Klein explains in her book This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate, confronts us to urgently change our means of production – yet much of the energy necessary for enacting real change is intercepted and diverted by conspiracy theories fantasizing about the shape of the planet (flat Earth), the release of psychoactive agents in the atmosphere (chemtrails), or even immigration.

Yes, immigration. The climate disaster has in fact brought about new mass movements of people from Africa, the Middle East, Asia, Latin America. Drought, extreme heat, floods, and hurricanes have made large parts of the planet uninhabitable, or almost uninhabitable; these disasters have torn the social fabric apart, and they are contributing to new wars. For instance, the conflict in Syria has important climatic causes. The climate crisis has forced people to leave their homes, and the situation is predicted to get worse. But in Italy and in a large part of Europe, a deflecting narrative has taken hold, a conspiracy theory, sometimes referred to as “the great replacement“, “ethnic substitution“, or the “Kalergi plan“. This is believed to be a plan to populate Europe and the West with Blacks, Muslims, and various people which threaten “our roots” or, in short, “our race”. And who is the puppeteer, the schemer driving world migrations? Of course George Soros. Why struggle with the criticism of political economy and climatology when the explanation is so simple?

We need debunking practices that recognize the needs addressed by conspiracy theories but present the core of truth without which no conspiracy theory could work.

Show the ‘seam’

Debunkers have sometimes asked magicians for help in unmasking spiritualists, clairvoyants, and psychics, i.e. magicians who try to pass off their tricks as authentic powers. It is a tradition that goes back to Harry Houdini, a dedicated enemy of spiritualism. James Randi unveiled the gimmicks of the psychic Uri Geller and the scams of the clairvoyant Peter Popoff. Silvan replicated the “psychic surgery” practiced in the Philippines. In the book ROL. Realtà O Leggenda? (‘ROL. Reality or legend?’), Mariano Tomatis explains the techniques of the psychic Gustavo Rol.

So far we have only brought the illusionists in to this story for the destructive part. It is time to work on the constructive part: how do we approach debunking in new, more effective ways?

In contemporary illusionism there are several experiments in “autodebunking”, that is, ways of revealing the trick behind the magic without ruining the enchantment. Rather, this can amplify the sense of wonder while transforming it to a level of greater awareness: from the simple astonishment of the effect, to the more complex astonishment of the techniques used – and the great effort required – to make the trick successful.

Mariano Tomatis recommends taking an example from the American duo Penn & Teller: “In two really surprising numbers (the “Cups and Balls” and “Lift Off of Love” tricks) the illusionists of Las Vegas unscrupulously reveal the trick used: this in no way threatens the awe of the performance, against all expectations. In the first part of the act, they appeal to emotion and irrationality; the second part, however, stirs up opposite pleasures […] which come from the appreciation of the technicalities behind the magic – the ‘seam’ that was not visible in the first part.” (“[I]n due numeri davvero sorprendenti (“Il gioco dei tre bussolotti” e “L’uomo tagliato in tre”) gli illusionisti di Las Vegas svelano senza scrupoli il trucco utilizzato: contro ogni aspettativa, ciò non minaccia in alcun modo lo stupore dell’esibizione. Nella prima parte del numero l’appello è all’emozione e all’irrazionalità; la seconda invoca un piacere di segno opposto […] che nasce dall’apprezzamento dei tecnicismi dietro la magia – quella ‘sutura’ che nella prima parte non si scorgeva.“)

That last sentence refers to the expression mostrare la sutura (‘showing the seam’), used on Wu Ming’s Giap blog to describe the act of claiming responsibility for Blissett’s pranks, and the use of “end credits” in some creative non-fiction.

In another number by Penn & Teller, one of the two magicians gets behind the wheel of a truck full of concrete blocks and drives over the other’s body, leaving him unharmed – and then the trick is explained, arousing even greater enthusiasm from the audience.

Wu Ming’s intervention in the QAnon debate was an attempt to weaken the conspiracy theory by showing its “seam”, that is, the similarities with the pranks of the Luther Blissett Project and the novel Q – while at the same time maintaining a sense of wonder, thanks to the evocation of Luther Blissett’s spirit.

The attempt was only partially successful, though. The conspiracy problem is not solved with a tactical intervention by a small group of pranskters, but rather with strategies developed and implemented by the highest number of people possible. From a mass movement.

Beyond QAnon

In late summer of 2018, conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, one of the people most responsible for the spread of Pizzagate and QAnon, was banned from Facebook, iTunes, YouTube, and Twitter. At the same time, as had already happened in the wake of Pizzagate, Reddit closed the QAnon forums on their platform because of content “encouraging or inciting violence and posting personal and confidential information”.

On 21 August 2018, two important Trump employees – former lawyer Michael Cohen and former campaign manager Paul Manafort – were found guilty of crimes related to the election of the president and his administration in trials accompanying the Mueller investigation, which is now closing in on the president.

In other situations, Trump’s base might have protested and demonstrated against the judicial storm that was about to hit their leader; instead, a small but significant part of that base has spent the last year raving about pedophiles and satanic dinners. They were convinced that the investigations were not true, and now they do not know what to think. For the first time, confidence in QAnon is faltering.

QAnon has distracted a part of the American right at a crucial time, and discredited a large share of Trump’s supporters. One could speculate that some part of the prank’s original intent has been effective after all; however, even if that were so, this outcome would not make up for the damage done: provoking millions of people with conspiracies of hate cannot be the way forward.

A Google Trends check on 21 October 2018 indicated that, after the August peak, interest in QAnon had dropped to pre-summer levels. Even Q’s “crumbs” are arriving on 8chan less and less frequently, with long intervals between one and the other.

On 24 October the Secret Service and police intercepted some letter bombs, very rudimentary devices, addressed to George Soros, Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, and other characters often targeted by Trump, the right, and – with the extreme twist we have seen here – QAnon. One of the recipients was actor Robert De Niro, who is despised by Trump’s supporters.

A few minutes after the news broke, QAnon’s followers were already on the defensive. They claimed it was an operation “under a false flag“: Clinton and the others had sent the bombs themselves. The umpteenth sub-theory of the plot was being set up, but with less verve than usual. The bombs were a ploy by pedophiles to blame Trump and help the Democrats in the mid-term elections.

And so, after almost a month of being out of the spotlight, the media started mentioning QAnon again, in articles about how the right were reacting to the letter bombs.

After years of describing their political enemies as the leaders of a satanic organization that keeps children in slavery and rapes them, the right would claim it is far-fetched – or so they pretend – that anyone would decide to take direct action and attack those enemies.

On 26 October, the FBI arrested Cesar Altieri Sayoc, 56, from Aventura, Florida. Sayoc is a fanatical Trump supporter, but to the QAnon community he was an actor: the arrest was fake and part of a false flag operation.

In general, the impression is that of fatigue. Maybe the game is wearing the players out.

At the end of the twentieth century moral panic over satanic ritual abuse would wane, but the legend was never gone: in Trump’s America, on the margins of public consciousness, it has returned to the main stage in Pizzagate and QAnon. Although QAnon may have currently lost its hold on the public, it will not disappear, and its main elements will continue to be reassembled. Sooner or later these elements are going to appear in new forms. And if the history of satanic ritual abuse teaches us anything – and the signs of the past few months are not just smoke without fire – it can happen in Italy, too.

On 18 September in Trieste, city councilman Fabio Tuiach, a former far-right Lega but now Forza Nuova politician, presented a motion against the artist Marina Abramović, calling her a “known Satanist“.

From part one of this story we know how the narrative develops: it begins as a rumor born with Pizzagate; it gets incorporated into QAnon and is brought to Italy by conspiracy theorist Maurizio Blondet; it is spread on social media by RAI president Marcello Foa; and eventually stories about ‘satanic rituals’ involving Abramović are reported in the newspaper Libero.

Alla fiera dell’ovest, per due soldi, la destra italiana una bufala comprò.

‘At the Western fair, for some pocket change, the Italian right has just bought itself a prank’. (Song to the famous tune of Angelo Branduardi.)