Some common-sense recommendations on cloudy computing

Today, Brussels-based lobby organisation ECIS released a report on

“cloud” computing and interoperability. It highlights the importance

of open standards, open data formats, and open interfaces in a world

where more and more of our computing happens on machines owned and

operated by other people.

The report is aimed at public and private organisations that want to

rent computing resources rather than buying the necessary hardware

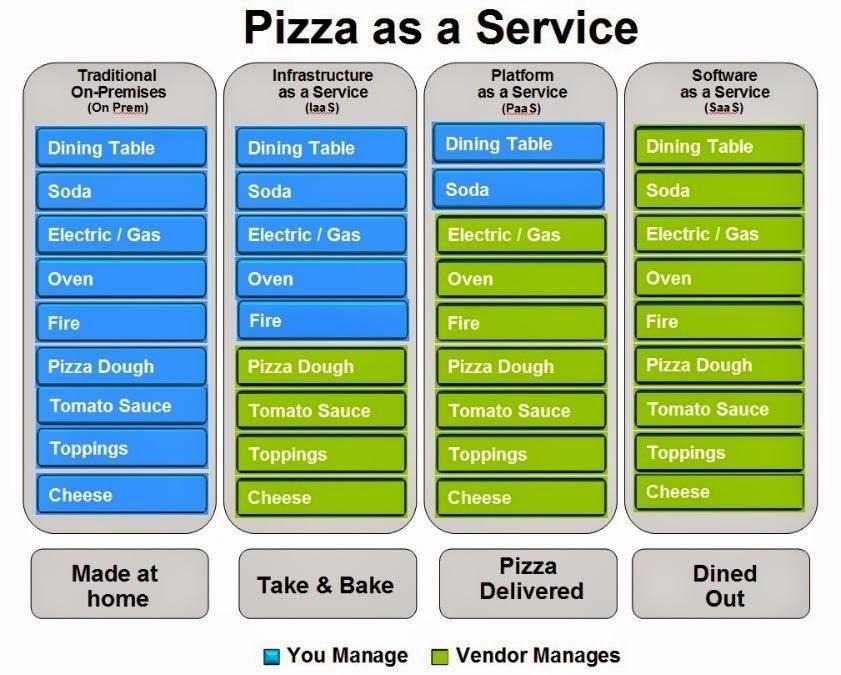

themselves. It covers three different scenarios – Software as a

Service (SaaS), Platform as a Service (PaaS), and Infrastructure as a

Service (IaaS).

The main report highlights questions that buyers —

including public sector procurement people – should ask before

signing on the dotted line.

The policy recommendations that come with the report common sense, and

boil down to caveat emptor. For example, the report asks policymakers to

“[e]stablish sets of criteria that help customers analyse and evaluate

migration and exit concerns before adopting and deploying cloud

computing solutions.” This basic bit of due diligence – assessing the

future cost of getting out of the system you’re buying – is something

that FSFE has long asked public bodies to undertake.

While the recommendations are hardly revolutionary stuff, Europe’s

public sector would be much better off if it took this advice to

heart. In reality, the most common scenario is likely to be an

underinformed public sector buyer facing a highly motivated vendor

salesperson. In order to avoid falling into future lock-in traps, it

will be essential to properly train procurement staff.

The report does have a couple of shortcomings. The authors are not

named, so the content perhaps deserves additional scrutiny. More

importantly, the report makes no mention of the data protection issues

that come with moving your data, and that of your customers, through

different jurisdictions. In the accompanying press release, ECIS gloss

over this issue with a tautology:

“[T]he value of the cloud lies in its global nature, and

fragmenting the cloud will inhibit the cloud.”

I asked about this issue at the event where the report was presented,

prompting the speaker, IBM’s Mark Terranova, to take prolonged

evasive action. There currently is no good answer to this

question. Buyers and users of these services should acknowledge that

as a problem.

At the heart of all this is the question of control. When you’re a

company that signs up for a service, who has control over your data,

your software, and your processes?

Even more lock-in?

While these services offer ease and flexibility, they also come with

the potential for even greater lock-in than the traditional model.

Being able to take your data to another service provider isn’t

enough. You also need to be able to carry along the associated

metadata that actually makes your data useful – if you just receive

your data in one big pile, a lot of the value is gone. If you’ve built

applications on top of your vendor’s service offering, you’ll want to

be able to move those to a new platform, too. Ian Walden pointed out

that these aspects don’t usually receive enough attention in contract

negotiations.

Pearse O’Donohue, who just moved from being Neelie Kroes’ deputy head

of Cabinet to a post as Head of Unit in DG CNECT, said that in the

EC’s own procurement, transparency and vendor-neutrality would be very

important in the future. He noted that with new EC, responsibility for

the EC’s procurement has moved from DG ADMIN to DG CNECT, under

Commissioner Oettinger and Vice-President Ansip. O’Donohue

highlighted that the new Commission is committed to “practicising

what it preaches” in public procurement.