Never ever has right to privacy been more threatened than now. The original idea of “interference with correspondence” has evolved around sneaky governments snooping in citizens private lives through intelligence agency workers steaming sealed letters. No one questions that secretly reading private letters is wrong. Digital has, however, blurred the lines of what is private or not, or what is intended to be private. Furthermore, users and consumers are being reassured that giving away their privacy and anonymity online is not a big deal. It is encouraged and claimed to be for our own good.

While our ways of communication and imparting information have changed, our basic human rights have not, despite the social media where it seems that we want to share the details of private lives, baby pictures and eating habits with the whole world. It might seem that due to this exhibitionist world we live in, no one should care about privacy any more. “D’oh silly, it’s internet!”.

Described as the greatest invention of humanity after the wheel, printing press, and light bulb, the internet brought us to a new era and transformed the way we live. It is unthinkable in the offline world to give up our privacy or any other fundamental right in order to receive better services or goods. That it is, for example, possible to circumvent the absolute prohibition of torture in order to get everyone’s life more convenient and fun. Sounds brutal but this is exactly what we are forced to do online by agreeing to endless terms of service in order to be able to communicate, impart information or express ourselves.

One might argue that neither right to privacy, nor freedom of expression are absolute, unlike the prohibition of torture. As we need to disclose our private information in certain cases, we cannot express ourselves the way we want: especially when our expression may harm others. However, there is a necessity to remind ourselves that human rights are inaliable, indivisible, and interdependent. And there is a reason why right to privacy and freedom of expression are often perceived together in courts. There is simply no one without the other.

“Anonymity” is closely linked to both of these rights, especially in the digital age, as it has contributed to a robust internet public sphere. The Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, Frank La Rue, called anonymity “one of the most important advances enabled by the internet, and allows individuals to express themselves freely without fear of retribution or condemnation“. What is helping to maintain the necessary anonymity is a strong end-to-end encryption. Demands to weaken this, either for the “national security” or “fight the terrorists” are weakening everyone’s security online, according to the Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, David Kay’s, about the use of encryption and anonymity in digital communications (‘the Report’, 22 may 2015).

Even if one is okay to reveal such details to the commercial actors for allegedly better and targeted ads, this bulk of data is a honey pot to the snooping governments and criminals. It is technically impossible to ensure that the data in question can be only accessed by legitimate powers. Backdoors can and will be used by everyone.

What is however often overlooked in the debate of human rights online is the right to hold opinions. While freedom of expression is not absolute and can be limited (e.g. hate speech), right to hold opinions is not allowed to be restricted by law or other power, according to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. The ability to hold an opinion freely was seen to be a fundamental element of human dignity and democratic self-governance during the negotiations of the Covenant. The Report emphasizes that the mechanics of holding opinions have evolved in the digital age and exposed individuals to significant vulnerabilities. Individuals regularly hold opinions online, saving their views and their search and browse histories, e.g. on hard drives, in the cloud, and in e-mail archives. Hence the balance between these three fundamental rights can be easily shaken, and the disturbance of one non-absolute right, even for allegedly legitimate reasons, will create the chain reaction that will lead to the more grave consequences. Strong encryption is necessary to preserve this balance.

Bruce Schneier has an excellent answer to everyone who claim they have nothing to hide or have no fear of surveillance. Encryption can save lives but only if we all do it. Using encryption only for sending sensitive data, indicates by its essence that the content is private or sensitive. This can be considered a basis per se for persecution or discrimination by authorities without even knowing what’s the content of that communication.

Everyone should care about privacy online because this is the only way to ensure that every individual, company, whistleblower, dissident, activist or not would feel safe to communicate, access and impart information, conduct business and express themselves in a safe way.

In light of last year’s Paris attacks, the debate over encryption has intensified. More voices are advocating for encryption with backdoors, or the ban of end-to-end encryption whatsoever. Achieving the goals of national security cannot be done without obeying to human rights law. Fortunately, not all governments are following this slippery slope, and do recognise the importance of strong encryption to society: for example in Netherlands, the government refused to take restrictive legal measures considering the development, availability and use of encryption within the country.

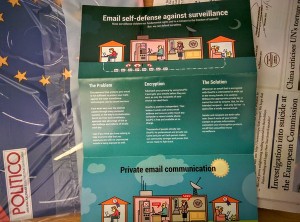

In the end of 2015, we wanted to remind policymakers how to secure their private communication online and distributed our ‘e-mail self-defense’ leaflets in the European Parliament.

Photo taken by Xander Bouwman, original can be found here.